Buddhadhamma

The Laws of Nature and Their Benefits to Life

by Bhikkhu P. A. Payutto

buddhadhamma.github.ioLast updated on: 2026-02-06

Downloads

Order Hard Copies

Copyright © Buddhadhamma Foundation 2021

This e-book is free to download from buddhadhamma.github.io. Distribution and commercial rights are reserved by the Buddhadhamma Foundation. If you wish to distribute this book from your website, please send your request to the Buddhadhamma Foundation.

Email: buddhadhammafoundationthai1987@gmail.com

Email: yongyutthanapura@gmail.com

Anumodanā

Although the Buddhist teachings on human conduct and relationships are diverse and numerous – according to the suitability for different individuals, communities, and circumstances, and in order to generate wholesome results at various times and in various places – they all converge at the same principles and modes of instruction. All of these teachings encourage people to live and act in harmony with an interrelated natural system functioning according to natural laws. If we are able to follow the guidance of awakened individuals conforming to this natural truth, or if we gain insight into this truth and practise accordingly, we will reap the desired results.

As the basic theoretical Buddhist teachings, which when realized lead to genuine satisfaction, are based on a truth connected to an interrelated natural system, there are additional practical teachings encouraging people to understand this truth. When realization of this natural truth occurs, people can use their understanding to engage with things in order to bring about favourable results, without needing to rely on teachers or external instruction. This is an inherent part of the natural system itself.

These two layers of teaching – the theoretical and the practical – are thus linked and form an integrated body of truth, pertaining directly to a natural order. ’The One Who Knows’, i.e. the Buddha, simply encouraged people to give heed to this truth of nature, so that they would realize it for themselves.

By clearly realizing this natural truth, one is no longer dependent on the advice and counsel of others. Buddhism thus contains no form of coercion; it neither forces anyone to believe in the teachings, nor is it troubled if people reject the teachings. It follows the principle that all things proceed naturally according to an interrelated system of causes and conditions. Having realized and discovered this truth for himself, the Buddha out of kindness and compassion gave instruction and guidance to others.

This book Buddhadhamma is an attempt to describe the Buddha’s teachings – which he systematized and set down as standard principles – on both levels: the basic theoretical teachings on truth and the practical teachings on personal conduct and social engagement, which are directly based on the theoretical teachings.

For many years, Khun Yongyut Thanapura has devoted himself to propagating the Dhamma. Towards the end of 1985, through his own initiative, he and other faithful lay supporters founded the Buddhadhamma Foundation. Although this foundation has no direct affiliation to the book Buddhadhamma or to its author, the foundation’s name was most likely chosen as a result of their sense of spiritual connection to this book.

As far as I am aware, from 1992 to the present – for almost twenty-three years – Khun Yongyut Thanapura has endeavoured to bring about an English translation of Buddhadhamma. He sponsored this work unremittingly, until erelong, two translated books were published: Good, Evil and Beyond: Kamma in the Buddha’s Teaching (translated by Bruce Evans, January 1993) – a translation of chapter 5 of Buddhadhamma titled ’Kamma’; and Dependent Origination: The Buddhist Law of Conditionality (translated by Bruce Evans, 1994) – a translation of chapter 4 of Buddhadhamma titled ’Paṭiccasamuppāda’.

Khun Yongyut Thanapura, the president of the Buddhadhamma Foundation, was determined to bring about a complete English translation of Buddhadhamma, containing all the chapters. Although he met with much difficulty and obstruction, spending a lot of money and having to wait a long period of time, he was undaunted and did not give up. The result is that now, after many years, a complete translated English edition is ready for publication.

The complete English translation of Buddhadhamma is the work of Mr. Robin Moore, who has been working on this translation for many years. Before working with the Buddhadhamma Foundation, while he was still ordained as a monk named Suriyo Bhikkhu, through his own enthusiasm, he began to translate these texts and published The Three Signs: Anicca, Dukkha, and Anattā in the Buddha’s Teachings, a translation of chapter 3 of Buddhadhamma titled ’The Three Characteristics’. On that occasion, in 2006, Khun Sirichan Bhirombhakdi and her two daughters, Khun Chuabchan and Khun Pornbhirom Bhirombhakdi, sponsored this publication for free distribution.

After leaving the monkhood, Mr. Robin Moore continued the translations of Buddhadhamma under the patronage of Khun Sirichan Bhirombhakdi and her two daughters, who published the following books for free distribution: Nibbāna: the Supreme Peace (2009; a compilation of material drawn primarily from chapters 6, 7 and 10 of Buddhadhamma on Nibbāna); Dependent Origination (2011; a translation of chapter 4 of Buddhadhamma titled ’Paṭiccasamuppāda’); and Awakened Beings: True Disciples of the Buddha (2014; a compilation of material drawn primarily from chapters 6, 7 and 18 of Buddhadhamma on enlightened beings). On this occasion it is thus appropriate to express a deep gratitude to Khun Sirichan Bhirombhakdi and her two daughters for supporting this translation work and giving the gift of Dhamma by publishing and distributing the translated editions of Buddhadhamma. Their efforts have nourished and sustained this translation work until it was linked with the project sponsored by the Buddhadhamma Foundation, thus helping to bring about this complete translated edition.

Over more than a decade that Mr. Robin Moore has been working on this project of translating Buddhadhamma, I am aware that Ven. Ajahn Jayasaro – through his kindness towards the translator, his love of Dhamma, and his wish to benefit students of Buddhism – has offered his assistance, both in terms of his knowledge of Dhamma and his linguistic skills, to the translator all through to the end. Here, I wish to acknowledge this kind, able, and virtuous assistance by Ven. Ajahn Jayasaro.

I wish to congratulate Khun Yongyut Thanapura, both for his individual efforts and his work as director of the Buddhadhamma Foundation. He has shown enduring charitableness towards Buddha-Dhamma, and has maintained fortitude, constancy, and perseverance, braving hardship and difficulty until the goal of completing the translation of Buddhadhamma has been achieved. He has played an important part in sustaining Buddhist study and practice and has spread the blessings stemming from the Dhamma on a wide scale.

On a similar note, I wish to express gratitude to Mr. Robin Moore, the translator, whose genuine and faultless efforts have brought this translation of Buddhadhamma to completion. These efforts have deservedly generated and radiated goodness and wholesomeness.

The original Thai edition of Buddhadhamma was written as an offering and dedication to the true Dhamma. As I mentioned in the ’Brief on Copyright of Translated Material’ (Nov. 9, 2009): ’All of my books are intended as a gift of the Dhamma, to be printed for free distribution, for the benefit of the wider public. There are no copyright fees for these books. If someone appreciates these books and with pure intent wishes to translate and share them … this is a way to propagate the Dhamma and perform good deeds for a wider audience. People engaged in such translations must rely on their skill and proficiency, and expend much time and energy…. The copyright to these translated works can thus be considered as belonging to the translator.’ What the translator then wishes to do with these translated texts is his or her responsibility to take into further consideration.

I wish to thank everyone who has participated in helping to bring this translated book into tangible form. May these efforts help to foster goodness and wellbeing, enhance spiritual development, and generate wisdom for all human beings, and help to create a stable and true human civilization.

Phra Brahmagunabhorn (P. A. Payutto)

21 November 2015

Abbreviations

(In the list below, canonical works are in italics)

| A. | Aṅguttaranikāya (5 vols.) |

| AA. | Aṅguttaranikāya Aṭṭhakathā (Manorathapūraṇī) |

| Ap. | Apadāna (Khuddakanikāya) |

| ApA. | Apadāna Aṭṭhakathā (Visuddhajanavilāsinī) |

| Bv. | Buddhavaṁsa (Khuddakanikāya) |

| BvA. | Buddhavaṁsa Aṭṭhakathā (Madhuratthavilāsinī) |

| Comp. | Compendium of Philosophy (Abhidhammatthasaṅgaha) |

| CompṬ. | Abhidhammatthasaṅgaha Ṭīkā (Abhidhammatthavibhāvinī) |

| Cp. | Cariyāpiṭaka (Khuddakanikāya) |

| CpA. | Cariyāpiṭaka Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthadīpanī) |

| D. | Dīghanikāya (3 vols.) |

| DA. | Dīghanikāya Aṭṭhakathā (Sumaṅgalavilāsinī) |

| DAṬ. | Dīghanikāya Aṭṭhakathā Ṭīkā (Līnatthapakāsinī) |

| Dh. | Dhammapada (Khuddakanikāya) |

| DhA. | Dhammapada Aṭṭhakathā |

| Dhtk. | Dhātukathā (Abhidhamma) |

| DhtkA. | Dhātukathā Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthadīpanī) |

| Dhs. | Dhammasaṅgaṇī (Abhidhamma) |

| DhsA. | Dhammasaṅgaṇī Aṭṭhakathā (Aṭṭhasālinī) |

| It. | Itivuttaka (Khuddakanikāya) |

| ItA. | Itivuttaka Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthadīpanī) |

| J. | Jātaka |

| JA. | Jātaka Aṭṭhakathā |

| Kh. | Khuddakapāṭha (Khuddakanikāya) |

| KhA. | Khuddakapāṭha Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthajotikā) |

| Kvu. | Kathāvatthu (Abhidhamma) |

| KvuA. | Kathāvatthu Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthadīpanī) |

| M. | Majjhimanikāya (3 vols.) |

| MA. | Majjhimanikāya Aṭṭhakathā (Papañcasūdanī) |

| Miln. | Milindapañhā |

| Nd1. | Mahāniddesa (Khuddakanikāya) |

| Nd2. | Cūḷaniddesa (Khuddakanikāya) |

| Nd1A. | Niddesa Aṭṭhakathā – Mahāniddesavaṇṇanā (Saddhammapajjotikā) |

| Nd2A. | Niddesa Aṭṭhakathā – Cūḷaniddesavaṇṇanā (Saddhammapajjotikā) |

| Nett. | Nettipakaraṇa |

| NettA. | Nettipakaraṇa Aṭṭhakathā |

| PañcA. | Pañcapakaraṇa Aṭṭhakathā |

| Paṭ. | Paṭṭhāna (Abhidhamma) |

| PaṭA. | Paṭṭhāna Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthadīpanī) |

| Ps. | Paṭisambhidāmagga (Khuddakanikāya) |

| PsA. | Paṭisambhidāmagga Aṭṭhakathā (Saddhammapakāsinī) |

| Ptk. | Peṭakopadesa |

| Pug. | Puggalapaññatti (Abhidhamma) |

| PugA. | Puggalapaññatti Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthadīpanī) |

| Pv. | Petavatthu (Khuddakanikāya) |

| PvA. | Petavatthu Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthadīpanī) |

| S. | Saṁyuttanikāya (5 vols.) |

| SA. | Saṁyuttanikāya Aṭṭhakathā (Sāratthapakāsinī) |

| Sn. | Suttanipāta (Khuddakanikāya) |

| SnA. | Suttanipāta Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthajotikā) |

| Thag. | Theragāthā (Khuddakanikāya) |

| ThagA. | Theragāthā Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthadīpanī) |

| Thīg. | Therīgāthā (Khuddakanikāya) |

| ThīgA. | Therīgāthā Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthadīpanī) |

| Ud. | Udāna (Khuddakanikāya) |

| UdA. | Udāna Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthadīpanī) |

| Vbh. | Vibhaṅga (Abhidhamma) |

| VbhA. | Vibhaṅga Aṭṭhakathā (Sammohavinodanī) |

| Vin. | Vinaya Piṭaka (5 vols.) |

| VinA. | Vinaya Aṭṭhakathā (Samantapāsādikā) |

| VinṬ. | Vinaya Aṭṭhakathā Ṭīkā (Sāratthadīpanī) |

| Vism. | Visuddhimagga |

| VismṬ. | Visuddhimagga Mahāṭīkā (Paramatthamañjusā) |

| Vv. | Vimānavatthu (Khuddakanikāya) |

| VvA. | Vimānavatthu Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthadīpanī) |

| Yam. | Yamaka (Abhidhamma) |

| YamA. | Yamaka Aṭṭhakathā (Paramatthadīpanī) |

Foreword by Ven. Ajahn Jayasaro

Buddhadhamma is the crowning achievement of Phra Brahmagunabhorn (P. A. Payutto), widely acknowledged as the most brilliant Thai scholar of Buddhism in living memory. The venerable author’s masterpiece, it is by some distance the most important Buddhist academic work to have been published in Thailand during the twentieth century.

Buddhadhamma consists of a rich and comprehensive presentation of the teachings of Theravada Buddhism. As a book dedicated to revealing the Middle Path of the Buddha in all its profundity, it is fitting that the text steers a skilful course between an unquestioning acceptance of ancient commentarial interpretations and a too wide-ranging rejection of their value. On controversial issues, such as Dependent Origination for example, the author fairly summarises the various positions on the debate and leaves it to the reader to decide amongst them. The arrangement of the material in the book is a departure from the norm, but it is a well-considered departure, one that provides the author with a satisfying frame on which to beautifully mount the many jewels of the Buddha’s teachings.

The venerable author’s use of language in this book has earned him wide renown in Thailand. It can, however, offer considerable challenges to a translator. Although the book is free of the elliptical phrases found in the works of many forest monks, the style is dense and given to unusual combinations of words that are stimulating in the original but occasionally overpowering in a literal translation. The translator of this book, Robin Moore, an old friend of mine and ex-fellow monk, has done a fine job in making the English version as accessible as possible, while maintaining an admirable fidelity to the text. It has been a labour of love on his part, and I salute him on behalf of all grateful readers.

Buddhadhamma has been my constant companion for over thirty years and is the book I would choose to have with me on a desert island. I would like to express my appreciation that finally an English translation will make this excellent book available to many more people.

Ajahn Jayasaro

Janamara Hermitage

June 2016

Foreword by the President of the Buddhadhamma Foundation

The Buddhadhamma Foundation is non-profit charitable organization, established by a group of devout Buddhists in 1987. Somdet Phra Buddhaghosacariya (P. A. Payutto) had no part in the establishment of this foundation or in any other matters pertaining to it.

The goal and objective of the Buddhadhamma Foundation is the widespread propagation of the Buddha’s teachings, so that people may benefit from them and apply them to solve problems, both personal and social, in everyday life, in accord with the Buddha’s directive to his disciples:

Bhikkhus, wander forth for the welfare and happiness of the manyfolk, for the compassionate assistance of the world.

Caratha bhikkhave cārikaṁ bahujanahitāya bahujanasukhāya lokānukampāya.

The inspiration for the establishment of the Buddhadhamma Foundation was the book Buddhadhamma, written by Ven. P. A. Payutto. Besides this text, the venerable author has written many books on how to apply the Buddha’s teachings to address problems and work out solutions in various domains, e.g.: education; society; economics; politics; government; jurisprudence; culture; history; health; medicine; family life; adolescence; self-development; Dhamma practice; mind development; sangha administration; remedying problems in the sangha; etc.

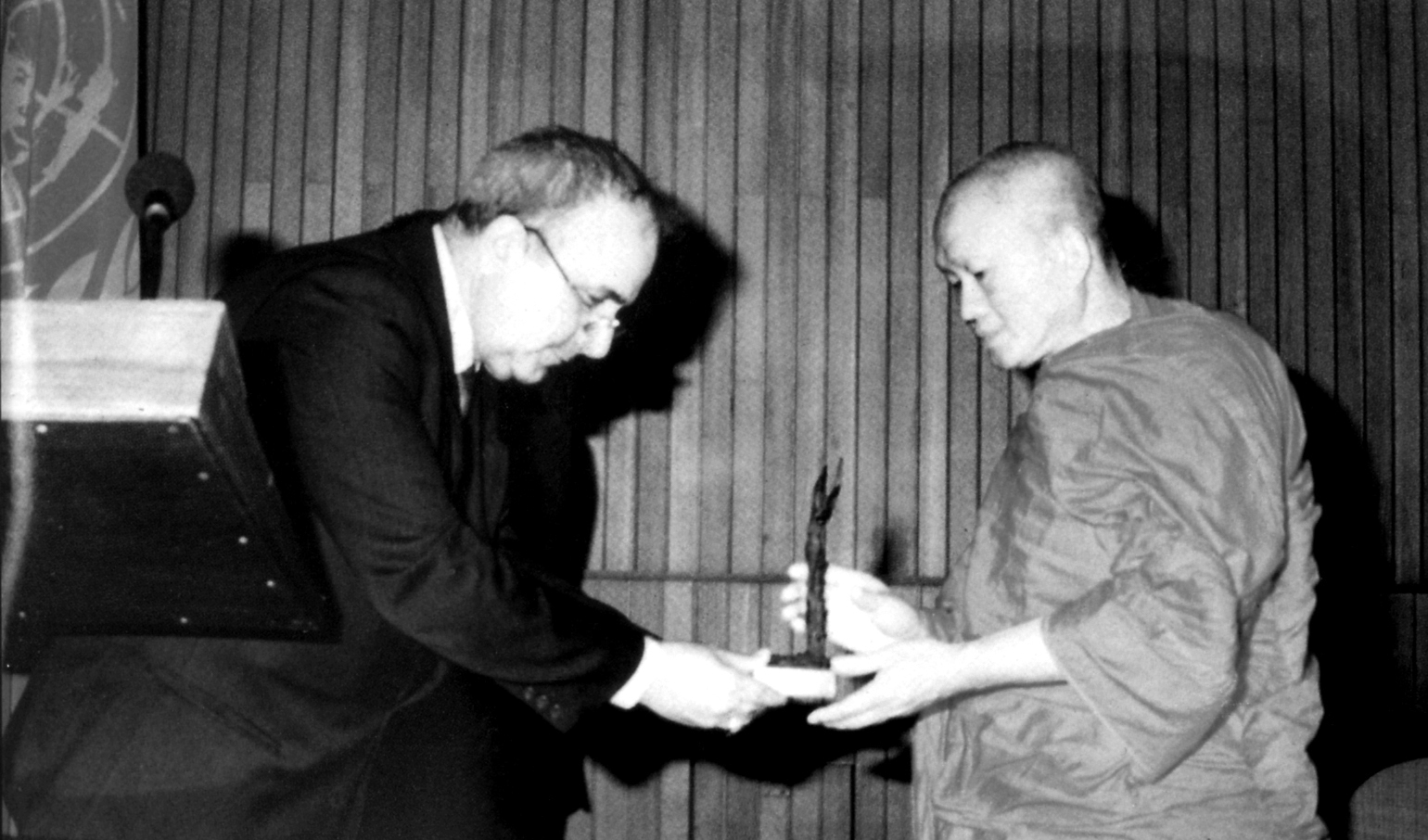

For his accomplishments Somdet Phra Buddhaghosacariya has been given honorary doctorate degrees from fifteen leading universities in Thailand, and in 1994 he received UNESCO’s Prize for Peace Education in Paris. The Buddhadhamma Foundation thus primarily focuses on propagating the Buddhist works written by Somdet Phra Buddhaghosacariya (P. A. Payutto).

Buddhadhamma was compiled by Ven. P. A. Payutto by drawing on the essence of the Buddha’s awakening, i.e. the Four Noble Truths. Ven. P. A. Payutto writes in a detailed, systematic, integrated, and logical way, revealing with clarity long-hidden truths to the reader. As a consequence, knowledge arises about the interconnected nature of human life and spiritual practice, from basic stages up to the final goal of life. One discovers the nature of human life, the attributes of life, the goal of life, and the means for living a worthy life. Through wise reflection one develops greater awareness and a transformation occurs in how one conducts one’s life, leading to fulfilment and success.

To finish, I would like to thank Somdet Phra Buddhaghosacariya for his kindness in permitting the Buddhadhamma Foundation to carry out this English translation of Buddhadhamma. I am delighted that Mr. Robin Moore has shown such commitment and donated his time to finish this translation in such a thorough and circumspect way. I also wish to express my appreciation to Mr. Bancha Nangsue, who has completed the computer and graphic work for this book with great diligence and determination. The foundation expresses its deep gratitude to all the other people (whose names are not mentioned here) who have provided support for this project and have helped to bring about its success.

The Buddhadhamma Foundation is happy for this English edition of Buddhadhamma to be shared and disseminated, both as a printed publication and over the internet, with the stipulation that this is not done in exchange for any form of profit or monetary reward. If anyone wishes to publish or share this book, please contact the Buddhadhamma Foundation first for permission.

I would like to offer this work in homage to the Triple Gem: the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha.

On this occasion, I wish to dedicate any goodness generated from the publication of this book to my late parents Mr. Rung Rueng and Mrs. Kulap Thanapura, and to my two children who have also passed away.

Yongyut Thanapura

President of the Buddhadhamma Foundation

1 June 2017

Contact:

Buddhadhamma Foundation

87/126 Thetsaban Songkhro Road

Khwaeng Lat Yao, Khet Chatuchak

Bangkok, 10900

Thailand

(Please send correspondence by registered mail.)

Tel: +66 (0)92-992-6962

Email: buddhadhammafoundationthai1987@gmail.com

Email: yongyutthanapura@gmail.com

Foreword by the Translator

It is said that a journey of a thousand miles begins with the first step. The first step, however, may be initiated by many different causes. The journey of completing this translation of Buddhadhamma in a sense began accidentally, or at least serendipitously.

In November 1994, after completing my 7-year training as an anāgārika (white-robed novice) and newly-ordained bhikkhu (nāvaka) in the monasteries situated in the UK led by Ven. Ajahn Sumedho (Tahn Chao Khun Rājasumedhācāriya), I asked permission from the elders in the UK to spend some time in Thailand, the spiritual home of the branch monasteries connected to the Luang Por Chah tradition. My request was granted and I was given a oneway ticket.

With only a rudimentary understanding of the Thai language, I went first to Wat Pah Nanachat in Ubon Ratchathani, where Ven. Ajahn Jayasaro was currently the acting abbot. Coincidentally, during the first month while I was there, the community was blessed with a rare visit by Ven. Phra Payutto, who spent several days giving teachings in English. I had of course heard of Tahn Chao Khun Payutto, whose scholarship was renowned in the Western monasteries and whose books – in particular his Dictionary of Buddhism – was widely read. I also knew that he had lectured at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, where I had studied comparative religion as an undergraduate.

During those days at Wat Pah Nanachat he gave a talk on happiness. Although I hadn’t ever heard anyone emphasize the central importance of happiness in Buddhist practice at all levels of the Path, it wasn’t so much the subject of the talk as the manner of the presentation that moved me so deeply. Than Chao Khun radiated happiness – he seemed to embody the joy of one who has tasted the fruits of happiness and who wishes to impart the accompanying knowledge with others. It is not an exaggeration to say that I was moved to tears. Although this was an inchoate form of bliss, based on devotion, it nonetheless infused me with energy and interest. His talk had served its purpose.

I spent most of the next six years walking tudong1 in Thailand as well as living in a remote branch monastery – Wat Phoo Jorm Gorm – by the Mekong River bordering Laos. As a monk, and even before that, I always had a strong academic leaning. Rather than using a standard course book or language teacher, I learned Thai primarily by carrying small Dhamma books (by Ajahn Buddhadasa, Tahn Chao Khun Paññānanda, Luang Por Chah, etc.) on my travels. For long periods of time these books were my companions. In 2001 I felt the need to deepen my theoretical or academic understanding of Buddhism, in part because as an 11-vassa monk (and thus officially a ’Thera’ or ’Ajahn’) I was expected to provide more formal teachings to the lay community.

I decided to ask permission from Ven. Phra Payutto to live with him at Wat Nyanavesakavan in Nakhon Pathom province. Ajahn Jayasaro took me to meet him. Rather than granting permission immediately, Tahn Chao Khun looked at me and asked: ’What are you going to do here?’ Obviously this was no place to simply eat and lay back. I replied that I wanted to read the Tipiṭaka in Thai. Tahn Chao Khun seemed satisfied with this answer.

Not long after moving to Wat Nyanavesakavan, I asked Tahn Chao Khun about the Buddhadhamma translation project. I knew that Mr. Bruce Evans (formerly Puriso Bhikkhu) had spent several years working on this book during the 90’s. Two of the chapters – on Dependent Origination and on Kamma – had been published and very well received. But for some reason, the project had come to a standstill. Tahn Chao Khun asked me whether I would be willing to look at the unfinished manuscript and see whether it could be polished up and made ready for publication. Very soon, however, it became apparent that editing or rewriting someone else’s work, at least in this case, was significantly more difficult than translating the entire text from scratch.

And so the journey began. At first it seemed like walking through a garden filled with exotic flowers, set on gentle foothills. I had no specific destination in mind. It was simply a matter of replacing my original goal of reading the Tipiṭaka with this new activity. I would joke with people, saying that it would take me several lifetimes to complete the entire translation.

In 2003 I returned to the UK and acted as abbot of Hartridge Buddhist Monastery in Devon. In my spare time I would work on the translation, until, in 2007, I completed chapter 3 (I chose not to work sequentially on the text, but rather selected subjects that were of particular interest to me at the time). This was published as a separate volume titled The Three Signs: Anicca, Dukkha and Anattā in the Buddha’s Teachings. The book was sponsored by Khun Sirichan Bhirombhakdi and her two daughters.

In 2007, after having struggled with a debilitating physical illness over the entire nineteen years of my monastic life, I decided to disrobe and see if life as a layman would bring about an improvement of health. Whereas it appeared as if the translation project would come to an abrupt halt, or enter a period of long abeyance, things in fact took an opposite turn, impelling me, metaphorically, from the foothills into elevated heights, where rhododendron trees bloom and the tree line gives out to expansive, moraine-sculpted valleys. Only weeks after disrobing in the UK I received a phone call from Khun Sirichan, urging me to return to Thailand and continue with the Buddhadhamma project. She made it clear that, in her mind, it was irrelevant whether I was in robes or not – she wished to support me and enable this valuable enterprise to be sustained. And so a new chapter of my life began.

Once in Thailand, I continued on the translation in earnest. Fortuitously, Khun Yongyut Dhanapura, the president of the Buddhadhamma Foundation, heard about the work I was doing and proposed that I continue with this project under the auspices of this organization. This enabled me to have all the proper documentation to stay longterm in Thailand and also to receive a salary so that I could earn a living. Here the journey began its most regular and consistent interval. One step at a time, one page of translation a day.

Although the actual translation of the text was completed in November 2014, it has taken another two years to attend to all the necessary details involved in preparing the text for publication. Ven. Ajahn Jayasaro kindly read through the manuscript and we met regularly to make corrections and improvements. After this, the entire formal preparation for publication began – selecting fonts, font sizes, margins and spacing, hyphenations, index, bibliography, contents, etc.

The journey now comes to end, although I hope the book itself will have a life of its own and travel into the world. Although I don’t claim to have reached a summit – that honour rests with the author – I have reached a high saddle or plateau, circumambulating with devotion Tahn Chao Khun’s crowning achievement. As a bonus I have been afforded rare glimpses and insights into the Dhamma. The project would never have reached this stage without devotion and love – a faith and devotion in Tahn Chao Khun’s ability to elucidate the Buddha’s teachings and a love of truth and goodness. Those of you who read the chapter on desire will recognize this latter quality as chanda – the first factor of the four roads to success.

It was perhaps an audacious step to use Buddhadhamma as my sharpening stone in learning the skills of translation. I was not a proficient translator or writer when I began this project. In this light, I have most likely not done full justice to the original Thai book. It is possible that I may have translated some passages incorrectly. If as readers you have doubt about any of the material, I have inserted the page numbers of the Thai edition into the text, in curly brackets, so that you can compare the English with the original. I have confidence, however, that with the help of my editors, in particular Ven. Ajahn Jayasaro, the book contains no blatant distortions or discrepancies.

Besides attempting to capture the meaning of the original Thai text, it has also been a challenge to find a suitable style of translation. Developing such a style was part of the evolution of translating this book. I think it is fair to say that the way in which ideas are formally conveyed in the Thai language differs from the traditional method of English compositions. One friend explained the distinction thus: Thai follows an inductive method whereas English traditionally follows a deductive method. Whether this is an accurate description or not, the text of the Thai edition of Buddhadhamma often follows what I would describe as a series of concentric circles, returning repeatedly to a similar premise. Using this same method in the English translation seemed inappropriate. If one is not used to this style, one can easily feel that, rather than adding layers of meaning and elucidation, one is encountering unnecessary repetition or redundancy. I have therefore reorganized the text accordingly, on many levels: paragraphs, chapter sections, and even entire chapters have been shifted. When key changes were made I consulted with the author to receive his approval. In any case, I can state with conviction that I have neither removed any important text or added my own interpolations.

One major task involved locating equivalent scriptural references used in the footnotes. This was not difficult with references to the Pali Canon, since the BUDSIR program (version 7) developed by Mahidol University contains a quick and easy to use search option for finding the corresponding Pali Text Society page numbers, matching the page numbers in the Thai Pali Tipiṭaka. The challenge was greatly multiplied, however, when faced with references to the commentaries, sub-commentaries, and other non-canonical texts. In most cases, I would have to copy the relevant Pali passage using the BUDSIR program, which does not give the PTS page numbers, and then try to match it by typing Pali terms in Roman script and pasting them into the Chaṭṭha Saṅgāyana Tipiṭaka program (version 4.0), which does provide pages numbers, or sometimes only headings, to the PTS editions. The BUDSIR program is based on the Siam Raṭṭha Pāli Tipiṭaka (supplemented by the Thai translation called the Royal Tipiṭaka) which is the source of the references in Buddhadhamma (see bibliography). It is quite possible that there are errors with some of these footnote references. If readers spot any errors I would be grateful if you contact me so that I can make corrections for future printings. In the case where numbers are in brackets this indicates that I was unable to find an equivalent PTS (or other Roman alphabet) page number. Again, hopefully these will be updated in the future.

So many people have been supportive and helpful with this project that it is impossible to name everyone. The most important people are as follows:

First and foremost, my gratitude extends to Ven. Phra Payutto, who, besides being a constant inspiration and beacon of wisdom and compassion, has bestowed so much trust and confidence in my ability to complete this project at a required quality and standard. Although, due to his many other responsibilities and limitations on the physical level, he has not been able to read through the entire English translation, he has always answered my questions and doubts punctually when they arose. Although I may have been able to reflect some of his depth of wisdom and intellectual brilliance, it is beyond my powers to transport his beaming smile and radiant kindness to the reader. Those of you who have had the good fortune to meet him know what I’m talking about.

Second, I give my thanks to Ven. Ajahn Jayasaro, who has provided me with so much encouragement on many levels throughout the past fifteen years (and beyond that). He shares a similar devotion to Tahn Chao Khun Payutto, as well as a love for language. Our time poring over this manuscript has deepened my respect for and friendship with him.

Third, I thank Khun Sirichan Bhirombhakdi for acting as the catalyst in bringing me back to Thailand to continue this work until it reached completion. Sometimes we must hear the words ’I believe in you’ to overcome inertia or other mental obstacles.

Fourth, this project would not have been completed without the enthusiasm and support by Khun Yongyut Thanapura, president of the Buddhadhamma Foundation. It was through his initiative and longterm vision that this book has materialized.

My mother and stepfather – Karin and Jon Gunnemann, and my father and step-mother – Basil and Subithra Moore, have given me material and emotional support over the years, including a time when I was between jobs. Important editors and proofreaders over the years include: Ven. Gavesako Bhikkhu, Ven. Cittasaṁvaro Bhikkhu, Ron Lumsden, Max Mackay-James, and Martin Seeger. I thank Mr. Bruce Evans for letting me consult with his earlier translations of Buddhadhamma, a work he did with great dedication. Other people who have provided notable support include Mr. Sian Mah and Mrs. Chantana Ouysook.

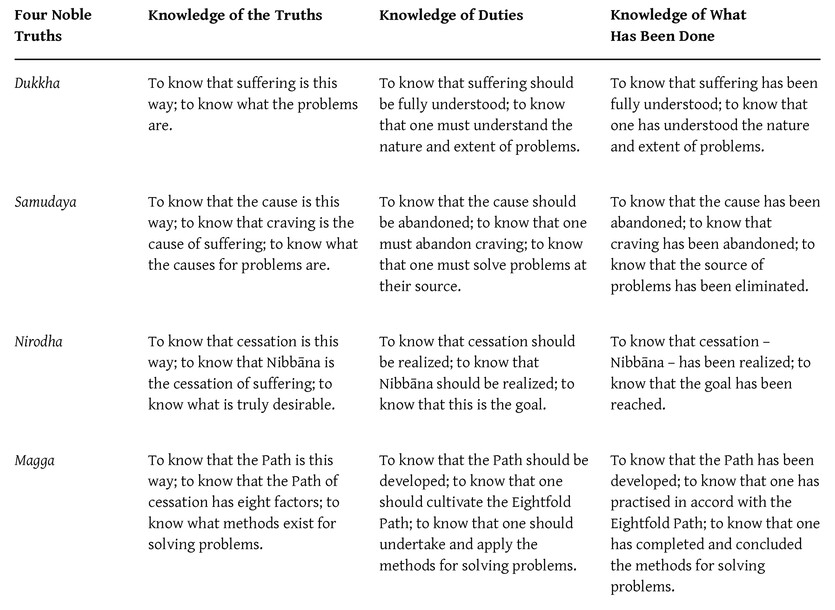

May these collective efforts help to bring light and peace to the world through the power of wisdom and understanding. The Buddha bequeathed the Dhammavinaya to us, to safeguard and uphold. This entails more than simply keeping copies of the Tipiṭaka in glass-fronted bookshelves. Although the realization of the Buddha’s teachings may be summarized as a fulfilment of the four duties vis-à-vis the Four Noble Truths, i.e. understanding suffering, removing its cause, realizing its cessation, and cultivating the Path, or more succinctly, knowing suffering and the end of suffering, many tools and skilful methods may be needed to accomplish this goal. The beauty of the Buddha’s teachings is that they provide us with a treasure chest of insights and guidelines. Another metaphor is that the Dhamma is a multifaceted diamond. No matter from what direction you pick it up, it offers invaluable glimpses of truth which may be used to cut through the shrouds of delusion. These teachings were expanded upon and elucidated by later commentarial authors. Ven. Phra Payutto’s gift and genius here is to present the canonical and post-canonical teachings in a lucid integrated whole, a watertight vessel for taking us to the other shore. The work to be undertaken is still ours to do, but the Path, and its many obstacles, has been clearly outlined and revealed.

Robin Moore

Green Park Home

August 2016

Introduction

People today frequently pose the question whether Buddhism is a religion, a philosophy, or simply a way of life. This query gives rise to all sorts of debates and opinions, which often just create confusion.

Although this book Buddhadhamma is written as a form of philosophical treatise, I will not engage in the aforementioned debate.1 My focus will simply be on what is stated in the Buddha’s teachings – on the gist of these teachings. As for the question whether Buddhism is a philosophy or not, it is up to various philosophical systems themselves to determine whether Buddhism fits their criteria. Buddhism remains what it is; it is unaffected by these judgements and interpretations. The only specification I wish to make here is that any teaching or doctrine on truth that is only intended as an intellectual exercise of logic or reason, and contains no corresponding elements for practical application in everyday life, is not Buddhism, especially the original and genuine teachings given by the Buddha himself, which are referred to as Buddha-Dhamma.

It is a difficult task to compile the Buddha’s teachings, especially on the premise that one is presenting the true or genuine teachings, even if one cites passages from the Pali Canon which are considered the words of the Buddha. This is because these teachings are copious and contain various dimensions or levels of profundity, and also because imparting them accurately depends on the intelligence and sincerity of the person presenting them. It may happen that two people with divergent opinions are both able to quote passages from the sacred texts supporting their own points of view. To determine the truth is dependent on how accurately one grasps the essence of these teachings, and on how consistent the link is between one’s theories and the evidence one uses to support them. In many cases the supporting evidence is not comprehensive enough, and thus it is inevitable that the presentation of Buddha-Dhamma often reflects the opinions and understanding of the person interpreting it.

To clarify one’s analysis of the teachings, it is helpful to examine the life and conduct of the Buddha, the supreme teacher, who is the origin and source of these teachings. {2} Although one may argue that the stories of the Buddha’s activities come from the same sources as the formal teachings, nonetheless they are very useful for reflection. Occasionally, the Buddha’s actions reflect his aims and wishes more clearly than the formal teachings in the scriptures.

From the evidence in the scriptures and from other historical sources, one can draw a rough sketch of the events and the social environment at the time of the Buddha as follows:

The Buddha was born in the Indian subcontinent about 2,600 years ago. He was born among the warrior caste (kṣatriyaḥ/katthiya), and named Prince Siddhattha. He was the son of King Suddhodana, the ruler of the Sakyan country, which lay at the northeast of the Indian subcontinent, adjoining the Himalayan mountain range. As a prince, and in accord with the wishes of the royal family, he was fully provided with worldly pleasures, which he enjoyed for twenty-nine years, during which time he was married and had a son.

At this time, absolute monarchies were in the ascendency and were trying to expand their empires by waging war. Many other states, especially the republics, who ruled by a general assembly based on unanimous decisions, were gradually losing their power. Some of these states were conquered and incorporated into larger states, while others that remained strong were under duress, aware that war could break out at any time. And the large, powerful nations were often at war with one another.

Trade and commerce were burgeoning, giving rise to a new group of highly influential wealthy merchants (seṭṭhi), whose prestige and authority began to extend even to the royal courts.

According to the teachings of Brahmanism, people were divided into four social classes or castes (vaṇṇa). People’s privileges and social standing, as well as their occupations, were determined by their caste. Although Hindu historians claim that the caste system at that time was not yet very strict, members of the class of manual workers (śūdra/sudda) were not entitled to listen to or to recite passages of the Vedas, the sacred texts of the brahmins. These restrictions became increasingly rigid and severe; śūdra who defied these injunctions and studied the Vedas were penalized with capital punishment. Moreover, outcastes (caṇḍāla) were not entitled to any form of formal education. The sole factor for determining one’s caste was birth, and the members of the brahmin class claimed to be superior to all others.

The brahmins safeguarded and upheld the traditions of Brahmanism. They developed ever greater arcane and mysterious teachings and rituals, which became increasingly irrational. Rituals were observed not simply for religious purposes, but also as a way for powerful rulers to demonstrate their importance. And the priests who conducted these rituals gained personal advantage and riches.

These ceremonies and rituals increased selfishness in those people seeking wealth and pleasure. At the same time, they caused distress for members of the downtrodden lower classes – the slaves, servants, and labourers – and they caused agony to those countless animals slaughtered as a sacrifice.2 {3}

During the same period, one group of brahmins doubted whether these religious rituals actually lead to eternal life, and they began to devote themselves to the contemplation of immortality and the path to its realization. In their search for truth, many of them separated themselves from society and resorted to the forests in seclusion. Such renunciants, who renounced the household life and went forth in search of the true meaning of life, were collectively referred to as samaṇa.

The brahmanical teachings during this time – the era of the Upanishads – was full of contradictions. Some religious factions affirmed the effectiveness of the established rituals, while other factions denounced these very same rituals. There were conflicting views on the subject of immortality and the soul (ātman). Some brahmins claimed that the ātman is equivalent to brahmin (Brahmā/Brahma; the godhead; the divine essence); they claimed that Brahma generates and permeates all things, and is ineffable, as is expressed in the phrase, neti neti (’not this, not that’). They believed that the ātman/brahmin unity is the supreme goal of spiritual practice. They engaged in religious debates on this subject, while at the same time jealously guarding knowledge on this matter within their own circles.

Meanwhile, another group of renunciants were disenchanted with the seeming meaninglessness of life, and practised in the hope of attaining exceptional states of mind or of reaching the deathless state. Some of them engaged in extreme forms of self-mortification, by fasting and undertaking strange and unusual ascetic practices, which ordinary people would not believe were possible. Others developed the concentrative absorptions (jhāna), reaching the fine-material attainments (rūpa-samāpatti) and the formless attainments (arūpa-samāpatti), while some became so proficient in the jhānas that they were able to perform marvels of psychic powers.

Included among the groups of renunciants were those who wandered from village to village, establishing themselves as teachers and expounding their various religious views by engaging in religious debate and dialectic.

The search for meaning and the propagation of various beliefs and teachings proceeded in an intense and energetic manner, leading to numerous ideologies and doctrines.3 As is mentioned in the scriptures, there were six major established doctrines at the time of the Buddha.4

To sum up, one group of people was growing in wealth and power, revelling in sensual pleasures and seeking increased riches. At the same time, many other people were neglected, and their social standing and quality of living was declining. Another group of people was separating itself from society, bent on discovering philosophical truths, but they too did not take much interest in the conditions of society.

Prince Siddhattha enjoyed worldly pleasures for twenty-nine years. Not only did his family provide him with such pleasures, they also prevented him from seeing firsthand the lives of the ordinary folk, which were full of suffering. This suffering, however, could not be concealed from him forever. The problems and afflictions of human beings – most notably aging, sickness, and death – preoccupied the prince and caused him to seek a solution. {4}

When the prince reflected on these social problems, he saw a group of privileged people who pursued their own personal comforts, competing with one another and indulging in pleasure, without any care or concern for the suffering of others. They were enslaved by material things. In times of happiness, they were engrossed in their own selfish pursuits; in times of affliction, they were obsessed with their own distress and despair. In the end, they grew old and sick, and died in vain. Another group of people, the disadvantaged, had no opportunity to prosper and were desperately abused and oppressed. They too aged, grew ill, and died in a seemingly meaningless way.

Seeing his pleasures and delights as pointless, the prince became disillusioned with his own life. Although at first his search was unsuccessful, he began to look for a solution, for a way to discover lasting and meaningful happiness. His life full of temptations and distractions was not conducive to his reflections. In the end he recognized that the renunciant life is uncomplicated, free from worry, and conducive to spiritual knowledge. He considered that this way of life would probably help him solve these universal human problems, and he may very well encounter renunciants who could teach him valuable lessons.

This line of thinking prompted the prince to relinquish the princely life and go forth as a renunciant. He wandered around studying with various teachers, learning the methods of spiritual endeavour (yoga) and developing meditation, until he reached the concentrative attainments (jhāna-samāpatti) – including the highest formless attainments (arūpa-samāpatti) – and became proficient at psychic powers (iddhi-pāṭihāriya). Eventually, he practised extreme austerities.

In the end he came to the conclusion that none of the methods belonging to these other renunciants were able to solve his conundrum. When he compared his present life to his earlier life in the palace, he realized that both were expressions of extremes. He decided to follow his own reflections and investigations, until he finally reached complete awakening.5 Later, when he proclaimed to others the truth, the Dhamma,6 that he had discovered, he referred to it as the middle truth (majjhena-dhamma) or the middle teaching (majjhena-dhammadesanā), and he referred to the system of practice that he laid down for others as the middle way (majjhimā-paṭipadā; the ’middle path of practice’).

The Buddhist perspective is that both a life of greed and indulgence – abandoning oneself to the stream of mental defilements – and a life of complete retreat from the world – giving up all involvement in and responsibility for society, and afflicting oneself with hardship – are incorrect and extreme forms of practice. Neither of these can lead people to a truly meaningful way of life.

After his awakening the Buddha returned to the wider society and began to teach the Dhamma in an earnest and devoted manner for the wellbeing of the manyfolk. He devoted himself to this task for the remaining forty-five years of his life.

The Buddha realized that sharing the teachings and helping others would be most effective through the renunciant form. He thus encouraged many members of the upper classes to renounce their wealth, go forth into the renunciant life, and realize the Dhamma. These individuals then participated in the work of self-sacrifice, devoting themselves to benefiting others, by wandering around the country and meeting with people of all social classes. {5}

The monastic community itself is an important medium for solving social problems. For example, every person, regardless of which caste or social class he or she comes from – even from the class of outcastes – has the same rights and privileges to be ordained, to train, and to reach the highest goal.

Merchants and householders, who are not yet prepared to fully renounce their possessions, may live as male and female lay disciples, supporting the monastic sangha’s activities and duties, and assisting other people by sharing their wealth.

The true objective and extent of activities by the Buddha and his disciples is summed up by the Buddha’s injunction, which he gave when he sent out the first generation of disciples to proclaim the teachings:

Bhikkhus, wander forth for the welfare and happiness of the manyfolk, out of compassion for the world, for the benefit, welfare and happiness of gods and humans.

Tv Kd 1 / Vin i 20-21, Mahākhandhaka

The Pāsādika Sutta offers a summary of how the Buddhist teachings are connected to society and how they benefit various groups of people:

The ’holy life’ (brahmacariya = the Buddhist religion) is only considered to have reached fulfilment, to be of benefit to the manyfolk, and to be firmly established – what is referred to as ’well-declared by devas7 and human beings’ – when the following factors are complete:

-

The Teacher (satthā) is distinguished, experienced, mature, and advanced in seniority.

-

There are bhikkhu elder disciples with expert knowledge, who are well-trained and fearless, who have realized the unsurpassed safety from bondage, who are able to teach the Dhamma to others effectively, and who successfully refute (opposing) doctrines correctly and in line with the Dhamma. Moreover, there are bhikkhus of middle-standing and newly ordained monks who have the same abilities.

-

There are bhikkhuni8 disciples – nuns who are senior, of middle-standing, and newly ordained – who have the same abilities.

-

There are male lay disciples, both those who live a celibate life and those who live at home and enjoy the pleasures of the senses, who have the same abilities.

-

There are female lay disciples, both those who live a celibate life and those who live at home and enjoy the pleasures of the senses, who have the same abilities.

Even lacking female householders with such virtuous qualities means that Buddhism is not yet prospering and complete.9

This sutta reveals how the Buddhist teachings are intended for everyone, both renunciants and householders. Buddhism embraces all of society. {6}

Primary Attributes of Buddha-Dhamma

The two main attributes of Buddha-Dhamma may be summarized as follows:

-

It reveals ’middle’ (i.e. ’objective’) principles of truth, and is thus referred to as the middle truth (majjhena-dhamma) or the middle teaching (majjhena-dhammadesanā). It reflects the truth in strict line with cause and effect and according to laws of nature. It has been revealed solely for the benefit of practical application in real life. It does not promote an attempt to realize the truth by creating various theories and dogmas based on philosophical conjecture and inference, which are consequently adhered to, debated and defended.

-

It lays down a system of practice referred to as the ’middle way’ (majjhimā-paṭipadā), which acts as a guideline for those undergoing spiritual training. These practitioners gain a clear insight into their lives, steer away from credulity, and aim for those fruits of practice accessible in this lifetime, namely: happiness, purity, enlightenment, peace, and liberation. In practical application the Middle Way is connected to other factors, such as one’s life as a renunciant or life as a householder.

Buddhism is a religion of action (kamma-vāda; kiriya-vāda), a religion of effort (viriya-vāda).10 It is not a religion of supplication nor is it a religion based on hope.

The practical benefits of the teachings are available to everyone no matter what his or her situation, beginning with the present moment. Regardless of a person’s station in or condition of life, everyone can access and utilize these teachings as is suitable to his or her circumstances, both in terms of understanding the Middle Truth and of walking the Middle Way. If one is still anxious or concerned about life after this world, one is encouraged to devote oneself through proper conduct to generating the desired favourable conditions now, until one gains confidence and dispels all worries and fears about the future life.11

Every person is equally eligible according to nature to reach the fruits of spiritual practice. Although people’s spiritual abilities differ, everyone should have equal opportunity to develop these wholesome results of practice according to his or her ability. Although each one of us must generate these results through individual effort – by reflecting on one’s full responsibility in these matters – we are all important agents for assisting the spiritual practice of others. For this reason, the Buddha stressed the two chief principles of heedfulness (appamāda) and virtuous friendship (kalyāṇamittatā). On the one hand, one takes full responsibility for one’s own life, and on the other hand one recognizes the supreme value of wholesome external influences.

The Buddha focused on several major tasks. One of these was his attempt to eliminate naive and superstitious beliefs around misguided religious ceremonies, in particular the practice of animal sacrifice (not to mention human sacrifice), by pointing out their harmful effects and overall fruitlessness. {7}

There were several reasons why the Buddha gave so much emphasis to abandoning the practice of sacrifices. First, these practices caused people to seek help from divine intervention. Second, they caused great hardship and affliction for other people and living creatures. Third, they increased selfishness and craving for material rewards. Fourth, they brought about a preoccupation with the future, rather than a wish to improve the present state of affairs. To counteract these detrimental practices, the Buddha emphasized generosity and service to society.

The second thing that the Buddha tried to abolish was the caste system, which used people’s birth as a way to restrict their privileges and opportunities, both in society and in regard to spiritual development. He established the monastic community, which welcomes people from all social classes into a system of equality, just as the ocean receives all rivers, as one unified and whole body of water.12 This then led to the institution of monasteries, which later became vital centres of education and the spreading of culture, to the point that Hinduism followed suit and created their own monastic institutions about 1,400-1,700 years after the Buddha.13

According to the principles of Buddha-Dhamma, both women and men are equally able to realize the highest goal of Buddhism. Not long after the Buddha had established the bhikkhu sangha, he also established the bhikkhuni sangha, despite social conditions being unfavourable to a female monastic order. The Buddha was fully aware of how difficult it would be to create a suitable form for women to live the renunciant life. He exercised great care in its establishment at a time when extreme restrictions around spiritual practice were placed on women by the religions of the Vedic period, to the extent that one may say the door had been closed to them.

The Buddha taught the Dhamma using vernacular language – the language used by the common people – so that everyone, regardless of his or her station in life or level of education, would be able to benefit. This was in contrast to Brahmanism, which insisted on the sacredness of the Vedic texts and used various means to reserve higher religious knowledge within a narrow, elite group. Specifically, the brahmins used the Sanskrit language, the knowledge of which was confined to their own group, to transmit and guard the texts. Later, some individuals asked the Buddha for permission to preserve and transmit the Buddhist teachings in the Vedic language, but he rejected this proposal and had the monks continue to use the language of the common people.14

Furthermore, the Buddha absolutely refused to waste time debating on matters of truth through philosophical speculation – on matters which cannot be empirically proven by way of rational discussion. If people came to him with such questions, the Buddha would remain silent. He would then lead the person back to everyday, practical matters.15 Those things to be understood by way of speech he would share with others by speaking; those things to be understood by way of sight he would reveal to others to see. He would use the most direct and appropriate method according to the circumstances.

The Buddha used many different methods when teaching the Dhamma, so that everyone may benefit. His teachings contain many layers: those aimed for householders and members of mainstream society, and those aimed for individuals who have relinquished the household life. There are teachings focusing on material benefits and others focusing on deeper, spiritual benefits. {8}

Because the Buddha taught within a brahmanic culture and was surrounded by various religious belief systems, he was required to engage with spiritual terms used by these other traditions. As the Buddha wished for his teachings to reach the greatest number of people within a short period of time, he applied a unique approach in regard to these terms. Rather than directly refuting or discrediting people’s beliefs associated with these terms, he questioned or challenged the true meanings of these terms. He did not use an aggressive approach; instead, he promoted a natural form of transformation through understanding and spiritual development.

To accomplish this the Buddha used some of these already established spiritual terms and gave them new meanings in line with Buddha-Dhamma. For example, he defined the term brahma/brahmā (’Brahma,’ ’divine,’ ’sublime,’ ’sacred’) as referring to one kind of celestial (yet mortal) being; in other contexts it was used in reference to parents. He altered the concept of worshipping the six cardinal directions into the notion of maintaining and honouring one’s social relationships. He changed the meaning of the sacred brahmanic fire worship, by the three kinds of sacrificial ceremonies, into fulfilling a responsibility vis-à-vis three kinds of individuals in society. And he transformed the factor determining a person as a brahmin (brāhmaṇa; ’one who is sacred,’ ’one who has divine knowledge’) and as noble (ariya; ’cultured,’ ’civilized’) from a person’s birth into a person’s conduct and spiritual development.

Occasionally, the Buddha encouraged his disciples to draw upon wholesome and beneficial aspects of other religious traditions. He acknowledged and approved of any teaching that is correct and connected to virtue, considering that such righteousness and virtue is a universal aspect of nature. In the case that specific principles of practice by these other traditions had varying interpretations, the Buddha explained which ones are correct and which ones are false. He sanctioned only the practice of what is correct and wholesome.

The Buddha pointed out that faulty or harmful practices observed by other religious traditions were sometimes a result of a decline or degeneracy within these traditions themselves. The original teachings espoused by these traditions were sometimes virtuous and correct. He occasionally described these original wholesome teachings. Examples of this include his historical explanations on the notions of ’religious austerity’ (tapa), the offering of sacrifices (yañña), the principles of leadership in regard to social assistance, and the duties of a brahmin (brāhmaṇa-dhamma).16

In the centuries following the Buddha’s death, after his teachings had spread to different areas, numerous disparities arose in people’s understanding of Buddha-Dhamma. This occurred for various reasons: those people who transmitted the teachings had different levels of training, understanding, and aptitude, and they interpreted the teachings in different ways; people began to mix in beliefs from other religious traditions; local cultures exerted an influence on people’s ideas and understanding; and some aspects of the teachings grew in prominence while other aspects fell into obscurity, due to the interest, predisposition, and skill of those individuals who safeguarded the teachings. These disparities resulted in the breaking off into various schools (nikāya), as is evident today in the division between Theravada Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism, along with numerous other subsidiary schools and lineages. {9}

Although the Theravada tradition is known for its precision and accuracy in preserving the original standards and teachings, it could not escape some changes and alterations. The authenticity and validity of some teachings, even those that are contained in the scriptures, are debated among members of the current generation, who often seek proof in order to either substantiate their own opinions or repudiate the views of others. Discrepancies are especially evident in the views and practices upheld by the general public. In some cases, these views and practices seem to stand in direct opposition to the original teachings, or they have almost developed into another religious ideology, perhaps even one refuted by the original teachings.

Take for example the understanding in Thailand of the word kamma (Sanskrit: ’karma’). Most Buddhists in Thailand when they encounter this word think of the past, in particular of deeds from past lives. They focus on the harmful effects in the present of bad deeds from past lives and on the negative results of previous evil actions. In most cases, their understanding is shaped by a collection of such thoughts. When compared to the true definitions of kamma in the scriptures, one can see how remote some of these ideas are from genuine Buddha-Dhamma.17

In this book the author18 is attempting to present Buddha-Dhamma in a way that is as true and accurate as possible. Because it is considered superfluous to this task, these divergent views, definitions, and practices are not discussed.

The source of the material for this book is the collection of Buddhist scriptures, which, unless otherwise specified, refers to the Tipiṭaka (Pali Canon). It is generally accepted that this text is the most accurate and complete compilation of the Buddha’s teachings. The author has selected those teachings in the Pali Canon which are deemed most authentic and accurate, by applying the principles of compatibility and coherence in respect to the overall body of Theravada scripture. As an added assurance in this undertaking, the author considers the Buddha’s conduct as a complement to the formal Dhamma teachings.

Having selected these guidelines, the author is confident that he has accurately explained and presented the true essence of Buddha-Dhamma.

On a fundamental level, however, the accuracy of this presentation depends on the extent of the author’s wisdom and intelligence, as well as any unacknowledged bias or prejudice. Let us simply conclude that this is one attempt to present the Buddha’s teachings in the most accurate way, based on specific methods of scholarship in which the author has the most confidence. {10}

One may separate Buddha-Dhamma into two parts, as matters of truth (sacca-dhamma) and matters of conduct (cariya-dhamma): as theory and practice. The former is defined as those teachings pertaining to reality, to manifestations of truth, to nature, and to the laws and processes of nature. The latter is defined as those teachings pertaining to principles of practice or behaviour, to benefiting in a practical way from one’s knowledge of reality or one’s understanding of the laws of nature. Sacca-dhamma is equated with nature and natural truths; cariya-dhamma is equated with knowing how to act in response to such truths. Within this entire teaching, no significance is given to supernatural agents – to any alleged forces over and above nature – for example of a creator God.

In order to do justice to the entire range and scope of Buddha-Dhamma as an integrated system, one should describe both of these aspects. That is, one should first reveal the theoretical teachings, followed by an analysis of how to apply these teachings in an effective and valuable way.

For this reason, the chapters in this book, each of which deals with a specific aspect of truth, also contain guidelines on how to apply these truths in a practical way. For example, at the end of the second chapter dealing with different kinds of knowledge, there is a section on the practical meaning and benefit of such knowledge. Moreover, the main body of Buddhadhamma follows this format: the first main section pertains to specific laws of nature, and is titled ’The Middle Teachings.’ The second main section pertains to a practical application of such laws in everyday life, and is titled ’The Middle Way.’

Although the presentation in this book may seem unorthodox, it corresponds to an original style of teaching. It begins with those aspects of life that are problematic, and it then traces back to the source of such problems. The analysis continues to a deeper inspection of the causes of suffering, the ultimate goal of spiritual practice, and the practical methods for solving problems and for realizing the goal. Indeed, the presentation is consistent with the Four Noble Truths.19

Part 1: Middle Teaching

Section 1: Nature of Human Life

‘Venerable sir, it is said, “the world, the world.” In what way, might there be the world or the description of the world?’

‘Where there is the eye, Samiddhi, where there are forms, eye-consciousness, things to be cognized by eye-consciousness, there the world exists or the description of the world. Where there is the ear … the mind, where there are mental phenomena, mind-consciousness, things to be cognized by mind-consciousness, there the world exists or the description of the world.’

Loko lokoti bhante vuccati kittāvatā nu kho bhante loko vā assa lokapaññatti vāti. Yattha kho samiddhi atthi cakkhu atthi rūpā atthi cakkhuviññāṇaṁ atthi cakkhuviññāṇa-viññātabbā dhammā atthi tattha loko vā lokapaññatti vā … atthi jivhā … atthi mano atthi dhammā atthi manoviññāṇaṁ atthi manoviññāṇa-viññātabbā dhammā atthi tattha loko vā lokapaññatti vā.

S. IV. 39-40

Where there is form, monks, by clinging to form, by adhering to form, there arises the view: ‘That which is the self is the world. Having passed away, I shall be permanent, lasting, eternal, not subject to change.’ When there is feeling … perception … volitional formations … consciousness … by clinging to consciousness … there arises the view: ‘That which is the self is the world. Having passed away, I shall be permanent, lasting eternal, not subject to change.’

Rūpe kho bhikkhave sati … vedanāya sati … saññāya sati … saṅkhāresu sati … viññāṇe sati, rūpaṁ … vedanaṁ … saññaṁ … saṅkhāre … viññāṇaṁ upādāya … abhinivissa evaṁ diṭṭhi upajjati so attā so loko so pecca bhavissāmi nicco dhuvo sassato avipariṇāmadhammo.

S. III. 182-83

Five Aggregates

The Five Constituents of Life

Introduction

From the perspective of Buddha-Dhamma, all things exist according to their own nature. They do not exist as separate fixed entities, and in the case of living creatures, they are not distinct and immutable ’beings’ or ’persons’, which one could validly take to be a legitimate owner of things or which are able to govern things according to their wishes.1

Everything that exists in the world exists as a collection of convergent parts. There exists no inherent self or substantial essence within things. When one separates the constituent parts from each other, no self or core remains. A frequent scriptural analogy for this is of a vehicle.2 When one assembles the various parts according to one’s chosen design, one assigns the conventional term ’wagon’ to the end product. Yet if one disassembles the parts, no essence of a wagon can be found. All that remains are the various parts, each of which is given its own specific name.

This fact implies that the ’self’ or ’entity’ of a vehicle does not exist separate from its constituent parts. The term ’car’, for instance, is simply a conventional designation. Moreover, all of the constituent parts may also be separated into further parts, none of which possesses a stable, fixed essence. So when one states that something ’exists’, one needs to understand it in this context: that it exists as a collection of inconstant constituent elements.

Having made this claim, the Buddhist teachings go on to describe the primary elements or constituents that make up the world. And because the Buddhist teachings pertain directly to human life, and in particular to the mind, this elucidation of constituent parts encompasses both mind and matter, both mentality (nāma-dhamma) and corporeality (rūpa-dhamma). Here, special emphasis is given to the analysis of the mind.

There are many ways to present this division into separate constituents of life, depending on the objective of the specific analysis.3 This chapter presents the division into the ’five aggregates’ (pañca-khandha), which is the preferred analysis in the suttas.

In Buddha-Dhamma, the human living entity – what is referred to as a ’person’ or ’living being’ – is divided into five groups or categories:4 {14}5

-

Rūpa (corporeality; body; material form): all material constituents; the body and all physical behaviour; matter and physical energy, along with the properties and course of such energy.

-

Vedanā (feeling; sensation): the feelings of pleasure, pain, and neutral feelings, arising from contact by way of the five senses and by way of the mind.

-

Saññā (perception): the ability to recognize and to designate; the perception and discernment of various signs, characteristics, and distinguishing features, enabling one to remember a specific object of attention (ārammaṇa).6

-

Saṅkhāra (mental formations; volitional activities): those mental constituents or properties, with intention as leader, which shape the mind as wholesome, unwholesome, or neutral, and which shape a person’s thoughts and reflections, as well as verbal and physical behaviour. They are the source of kamma (’karma’; intentional action). Examples of such mental formations include: faith (saddhā), mindfulness (sati), moral shame (hiri), fear of wrongdoing (ottappa), lovingkindness (mettā), compassion (karuṇā), appreciative joy (muditā), equanimity (upekkhā),7 wisdom (paññā), delusion (moha), greed (lobha), hatred (dosa), conceit (māna), views (diṭṭhi), jealousy (issā), and stinginess (macchariya). They are the agents or fashioners of the mind, of thought, and of intentional action.

-

Viññāṇa (consciousness): conscious awareness of objects by way of the five senses – i.e. seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, and feeling tangible objects – and awareness of mind objects.

There are several points to bear in mind in reference to the final four aggregates, comprising the mental aggregates (nāma-khandhā):8

Perception (saññā) is a form of knowledge.9 It refers to the perception or discernment of an object’s attributes and properties, including its shape, appearance, colour, and so on, as well as its name and conventional designations. For example, one knows that an object is ’green’, ’white’, ’black’, ’red’, ’loud’, ’faint’, ’bass’, ’high-pitched’, ’fat’, ’thin’, ’a table’, ’a pen’, ’a pig’, ’a dog’, ’a fish’, ’a cat’, ’a person’, ’him’, ’her’, ’me’, ’you’, etc.

Perception relies on the encounter or comparison between previous experience or knowledge and new experience or knowledge. If one’s current experience corresponds with previous experience – say one meets a familiar person or one hears a familiar sound – one has ’recognition’ (note that this is not the same as ’memory’). For example, Mr. Jones is acquainted with Mr. Smith. A month later, they meet and Mr. Jones recognizes Mr. Smith. {15}

If a new experience does not correspond with previous experience, people tend to compare it to previous experience or knowledge, looking at those aspects that are either similar or different. They then identify the object according to their labels or designations, determined by the similarities and differences. This is the process of perception – of designation and identification.

There are many layers to perception, including: perception in accord with common agreement and understanding, e.g.: ’green’, ’white’, ’yellow’, and ’red’; perception in accord with social conventions and traditions, e.g.: ’this is polite’, ’this is beautiful’, ’this is normal’, and ’this is abnormal’; perception according to personal preferences and conceptions, e.g.: ’this is attractive’, ’this is admirable’, and ’this is irritating’; perception based on multiple factors (perception of symbolism), e.g.: ’green and red symbolize this university’, and ’two rings of the bell designate mealtime’; and perception according to spiritual learning, e.g.: ’perception of impermanence’ and ’perception of insubstantiality’.

There is both common, everyday perception and subtle, refined perception (that is, perception that is intricately connected to the other aggregates). There is perception of matter and perception of the mind. The various terms used for saññā, such as ’recognition’, ’remembering’, ’designation’, ’assignation’, ’attribution’, and ’ideation’ all describe aspects of this aggregate of perception.

Simply speaking, perception is the process of collecting, compiling, and storing data and information, which is the raw material for thought.

Perception is very helpful to people, but at the same time it can be detrimental. This is because people tend to attach to their perceptions, which end up acting as an obstruction, obscuring and eclipsing reality, and preventing them from penetrating a deeper, underlying truth.

A useful and practical division of perception (saññā) is into two kinds: ordinary perceptions, which discern the attributes of sense objects as they naturally arise; and secondary or overlapping perceptions. The latter are sometimes referred to by specific terms, in particular as ’proliferative perception’ (papañca-saññā): perception resulting from intricate and fanciful mental proliferation driven by the force of craving (taṇhā), conceit (māna), and views (diṭṭhi), which are at the vanguard of negative mental formations (negative saṅkhāra). This division highlights the active role of perception and shows the relationship between perception and other aggregates within mental processes.

Consciousness (viññāṇa) is traditionally defined as ’awareness of sense objects’. It refers to a prevailing or constant form of knowing. It is both the basis and the channel for the other mental aggregates, and it functions in association with them. It is both a primary and an accompanying form of knowledge.

It is primary in the sense that it is an initial form of knowledge. When one sees something (that is, visual consciousness arises), one may feel pleasure or distress (= feeling – vedanā). One then identifies the object (perception – saññā), followed by various intentions and thoughts (volitional formations – saṅkhāra). For example, one sees the sky (= viññāṇa) and feels delighted (= vedanā). One knows the sky to be bright, beautiful, the colour of indigo, an afternoon sky (= saññā). One is delighted by the sky and wishes to admire it for a long, uninterrupted period of time. One resents the fact that one’s view is obstructed, and one wonders how one can find a place to watch the sky at one’s leisure (= saṅkhāra).

Consciousness is an accompanying form of knowledge in that one knows in conjunction with the other aggregates. When one feels happy (= vedanā), one knows that one is happy (= viññāṇa). (Note that the feeling of happiness is not the same as knowing that one is happy.) When one suffers (= vedanā), one knows that one is suffering (= viññāṇa). Perceiving something as pleasurable or painful (= saññā), one knows accordingly.10 And when one engages in various thoughts and intentions (= saṅkhāra), there is a continual concomitant awareness of this activity. {16} This prevailing stream of awareness, which is in a continual process of arising and ceasing, and which accompanies the other mental aggregates, or is part of every aspect of mental activity, is called ’consciousness’ (viññāṇa).

Another special characteristic of consciousness is that it is an awareness of particulars, a knowledge of specific aspects, or a form of discriminative knowledge. This may be understood by way of examples. When one sees say a striped piece of cloth, although one may not initially identify it as such, one discerns specific attributes, for example its colours, which are distinct from one another. Once consciousness discerns these distinctions, perception (saññā) identifies them, say as ’green’, ’white’, or ’red’. When one eats a particular kind of fruit, although one may not yet have identified the flavour as ’sweet’ or ’sour’, one already has an awareness of such distinctions. Similarly, although one may have not yet distinguished between the specific kinds of sourness, of say pineapples, lemons, tamarind, or plums, or between the specific kinds of sweetness, say of mangos, bananas, or apples, by tasting the flavour one is aware of its distinctive nature. This basic form of knowing is consciousness (viññāṇa). Once this awareness arises, the other mental aggregates begin to operate, for example one experiences the flavour as delicious or unsavoury (= vedanā), or one identifies the flavour as one particular kind of sweetness or sourness (= saññā).

The knowledge of specific aspects referred to above may be explained thus: when consciousness arises, for example when one sees a visual object, in fact one is seeing only specific attributes or facets of that object in question. In other words, one sees only those aspects or angles that one gives importance to, depending on the mental formations (saṅkhāra) which condition the arising of consciousness (viññāṇa).11

For example, in a wide expanse of countryside grows one sole mango tree. It is a large tree, yet it bears only a few pieces of fruit and in this season is almost barren of leaves, providing very little shade. On different occasions, five separate people visit this tree. One man is fleeing from a dangerous animal, one man is starving, one man is hot and looking for shade, one man is searching for fruit to sell at the market, and the last man is looking for a spot to tie up his cattle so that he may visit a nearby village.

All five men see the same tree, but each one sees it differently. For each man eye-consciousness arises, but this consciousness varies, depending on their aims and intentions in regard to this tree. Similarly, their perceptions of the tree will also differ, according to the aspects of the tree that they look at. Even their feelings (vedanā) will differ: the man fleeing from danger will rejoice because he sees a means to escape; the starving man will be delighted because the 3-4 mangos will save him from starvation; the man suffering from heat may be disappointed because the tree does not provide as much shade as it normally would; the man looking for fruit may be upset because of the paucity of fruit; and the man driving his cattle may be relieved to find a temporary shelter for them.

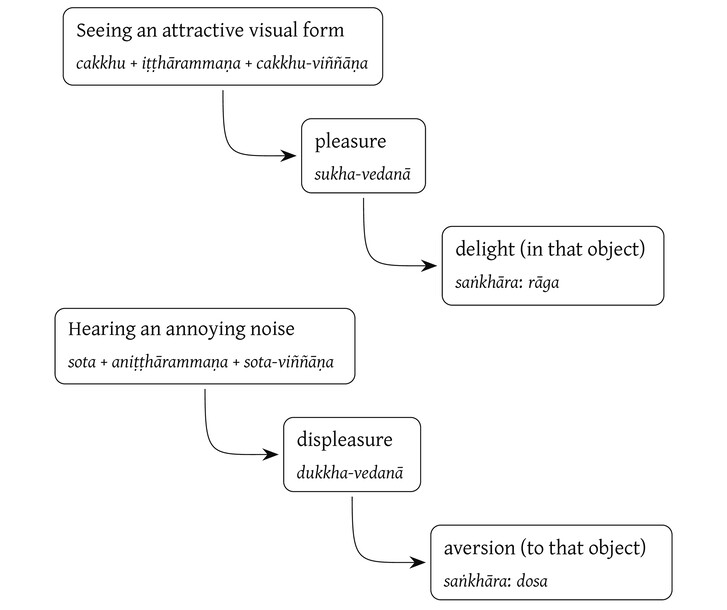

Feeling (vedanā) refers to the ’sensing’ of sense impressions, or of experiencing their ’flavour’. It refers to the feeling or sensation arising every time there is contact and cognition of sense objects. These feelings may be pleasurable and agreeable, painful and oppressive, or neutral. {17}

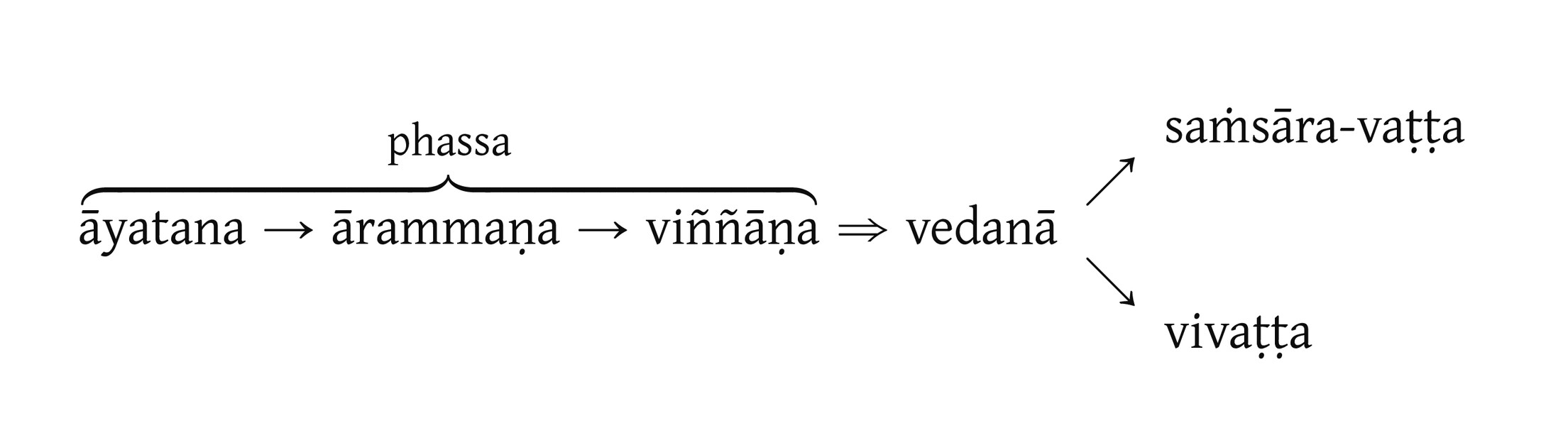

To avoid confusion with the aggregate of mental formations (saṅkhāra), it is important to note that feeling (vedanā) is an activity at the level of reception – it pertains exclusively to the immediate effect an object has on the mind.12 It does not pertain to the stage of intention or of acting in response to sense impressions, which is the function of mental formations (saṅkhāra). For this reason, such terms as ’like’, ’dislike’, ’delight’, and ’aversion’ usually refer to the activity of mental formations, which involves a subsequent level of activity. These terms normally refer to volitional activities or to reactions to sense impressions, as illustrated on Figure Feeling (Vedanā) and Mental Formations (Saṅkhāra) about mental processes.

Feeling (vedanā) plays a pivotal role in the lives of sentient creatures because it is both desired and sought after (in the case of pleasure), and feared and avoided (in the case of pain). Each time there is contact and cognition of a sense object, feeling acts as the juncture, directing or motivating the other mental factors. For example, if one contacts a pleasurable sense object, one pays special attention to it and perceives it in ways that reciprocate or make the most out of that sensation. One then thinks up strategies for repeating or extending one’s experience of this object.

Mental formations (saṅkhāra) refer to both the factors determining the quality of the mind (the ’fashioners’ of the mind), with intention (cetanā) as chief, and the actual volitional process in which these factors are selected and combined in order to shape and mould one’s thoughts, words, and deeds, resulting in physical, verbal, and mental kamma.