Wise Reflection

Forerunners of the Middle Way

Initial Stage of Practice 2:

Yoniso-manasikāra

The Role of Reflection in a Wholesome Way of Life

For people to find true happiness they must live their lives correctly and relate to things properly, including their own personal lives, their society, technology, and their natural environment. Those people who live their lives correctly experience a personal happiness inherently conducive to the happiness of others.

The expression to live one’s life correctly, or to relate to all things properly, is a general or undetailed reference to spiritual practice. For a clearer description one must separate and distinguish correct practice into various minor activities, and examine many aspects of a person’s life. It is useful therefore to describe the different parts of spiritual practice, which together comprise the entirety of living one’s life correctly. Hereby, one defines the subtleties of living correctly, revealing the different aspects of proper practice.

From one perspective, to live one’s life is to struggle for survival, to try and escape from oppressive and obstructive forces, and to discover wellbeing. In brief, this aspect to life is the solving of problems or the ending of suffering. Those people who are able to solve and escape from problems correctly reach true success in life and live free from suffering. Therefore, to live correctly and with success can be defined as an ability to solve problems.

From another perspective, to live one’s life is to engage in various activities, manifesting as different forms of physical and verbal behaviour. When such activity is not expressed outwardly, then it manifests internally, as mental behaviour. This refers to acts of body, speech and mind, which are technically referred to as volitional physical actions (kāya-kamma), verbal actions (vacī-kamma), and mental actions (mano-kamma). Collectively, they are referred to as kamma by way of the three ’doorways’ (dvāra).

From this perspective life consists of engaging in these three kinds of actions. Those people who perform these three actions correctly live their lives well. Therefore, to live correctly and with success can be defined as knowing how to act, speak, and think – to be skilled at performing physical actions (including one’s work and profession), speaking (or communication in general), and thinking. {608}

From yet another perspective, an analysis of human life reveals that it consists of various forms of cognition, of experiencing objects of awareness or sense stimuli, which are collectively referred to as ’sense objects’ (ārammaṇa). These sense impressions pass through or manifest by way of the six sense bases (āyatana): the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, and mind. The receiving of these sense impressions consists of seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, contacting tactile impressions, and cognizing mind objects: i.e, to see, to hear, to smell, to taste, to feel physical feelings, and to think.

The response and attitudes of people in regard to cognition of these sense stimuli have a crucial bearing on their lives, conduct, and fortune. If they respond to sense impressions solely with delight and aversion, with likes and dislikes, the chain of distress is set in motion. If they respond in the manner of recording information, however, and see things according to the truth – see things according to cause and effect – they will go in the direction of wisdom and towards a true solution to problems.

A factor that is no less vital than the response and attitudes towards sense impressions is the ability to select sense objects. For example, one may incline towards and choose to listen to and watch those things which gratify desire, or one may choose to listen to and observe those things that support wisdom and enhance the quality of the mind.

From this perspective to live correctly and successfully can be defined as knowing how to receive and select sense impressions – to be skilled at seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, contacting tactile objects, and thinking.

There is one more perspective to take into consideration. One way to describe human life is to highlight the engagement and relationship to phenomena in order to derive benefit from these things.

For most people the consumption or enjoyment of sense pleasures plays a very significant role. When engaging with people or things in their surroundings, whether this be their society or the natural environment, most people seek to derive some kind of benefit or advantage from them in order to satisfy their wishes or to gratify their desires. In other words, when they wish to satisfy desires they go out and engage with these people and things.

The preceding factor – of looking at life as a process of cognition – contains two aspects: that of pure cognition, say of seeing and hearing, and that of engagement, say of looking and listening. The skill of receiving and selecting sense impressions (e.g. a skill at seeing or hearing) is related to this factor of engagement.

To engage with or to consume things properly is a vital factor in determining and shaping a person’s life and degree of happiness. Therefore, to live correctly and successfully can be defined as being skilled in engaging with and relating to things. In the context of society this refers to knowing how to relate and associate with other people. In the context of material things and the natural environment this refers to knowing how to use and consume things properly.

In sum, a correct and successful way of life encompasses several subsidiary forms of behaviour and consists of various aspects, notably:

-

From the perspective of escaping from problems, one is skilled at solving them.

-

From the perspective of performing actions, one is skilled at thinking, speaking (or communicating), and performing physical deeds.

-

From the perspective of receiving sense impressions, one is skilled at seeing, listening, smelling, tasting, contacting tactile impressions, and thinking.

-

From the perspective of engagement or consumption, one is skilled at using and consuming things, and at relating to other people. {609}

To practise these various aspects of life properly is referred to as ’living one’s life correctly’, ’knowing how to live’, or ’being skilled at conducting one’s life’. According to Buddha-Dhamma, a life lived in such a manner is considered a virtuous life.

These various aspects of life, or aspects of spiritual practice, can be summed up by the phrase: ’knowing how to think’ or ’being skilled at reflection’. They all involve the process of thinking, which is a vital factor for living one’s life correctly. Thinking plays an important role on many levels, including:

-

In the context of cognition, thinking is the meeting point, where various information and data gathers and assembles. It is where data is analyzed, shaped, and applied.

-

In the context of volitional actions, thinking is the starting point, which leads to outward verbal and physical expressions – to speech and physical action. Moreover, it is the command centre, which determines or controls speech and physical deeds, according to one’s thoughts.

-

In the relationship between these two forms of behaviour, thinking is the centre point – it is the link between cognition and volitional actions. When one experiences things by way of the sense bases, and then gathers, processes, and analyzes this sense data, thinking dictates the consequent outward expressions of speech and physical actions.

In sum, correct thinking or the skill of reflection is the seat of administration in regard to correct living in its entirety. It is the leader, guide and director for all other aspects of right practice. When one is able to think correctly, one is also able to speak correctly, act correctly, and solve problems correctly. One is skilled at seeing, hearing, eating, using material things, consuming things, and associating with others – one is skilled at living. A skill in thinking and reflection leads to a virtuous life.

A decisive factor determining a person’s skill in regard to volitional action is spiritual balance. Generally speaking, in this context the terms ’skill’ and ’balance’ have the same meaning. To act skilfully is to act in a correct, even way, giving rise to desired results according to one’s intentions and objectives. One acts in a way that is accurate, coherent, direct, and consistent, enabling one to reach one’s goal in the most optimum way, without creating any kinds of harm or faults.

In the context of reaching one’s goal, the Buddhist teachings give great emphasis to the characteristics of faultlessness, freedom from affliction, and suitability, the meanings of which are encompassed in the word ’spiritual balance’. Thus the term ’skill in conducting one’s life’ can be defined as ’living a balanced life’: to live with moderation and in a suitable way in order to attain the goal of life in a truly blameless and joyful manner.

The technical term for a life of balance, for suitable practice, or for a virtuous life is the ’middle way’ (majjhimā-paṭipadā), which refers to the Path (magga): the Noble Eightfold Path. The Middle Way is the virtuous, sublime life, free from harm and affliction, leading to utter safety and complete happiness.

Buddha-Dhamma teaches that in order to live correctly or to lead a virtuous life one must pass through a process of spiritual training and study. One can say that the Path arises as a result of spiritual training. Just as skilful reflection is the guiding principle of a virtuous life or of the Path, so too, cultivating one’s skills in the area of thinking is the leading factor in formal spiritual training (sikkhā). {610}

Within the process of spiritual training, developing a skill in reflection leads to correct understanding, correct ideas, and even correct beliefs, which are collectively referred to as ’right view’ (sammā-diṭṭhi), which is the mainstay of a virtuous life in its entirety. The cultivation of right view is the gist of wisdom development, which is at the heart of spiritual training.

A skill in reflection involves many methods of thinking and analysis. Developing such skill in reflection is a unique form of spiritual training and cultivation.

The Role of Reflection in Spiritual Training and Wisdom Development

Before discussing the various methods of thinking, let us review the role of thinking in spiritual training, especially in the area of wisdom development, which is the core of such training.

Commencement of Training

The essence of spiritual training is self-development, with wisdom development at its core. The key elements of such training are correct understanding, opinions, ways of thinking, attitudes, and values, which benefit one’s life and society and conform to truth. In short, this refers to ’right view’ (sammā-diṭṭhi).

When one understands things correctly, one’s thoughts, speech, and physical actions – that is, all of one’s actions – will be correct, virtuous, and beneficial, leading to the end of suffering.

Conversely, if one has incorrect understanding, values, attitudes, and ways of thinking – collectively referred to as ’wrong view’ (micchā-diṭṭhi) – all of one’s actions, including one’s thoughts, speech, and physical actions, will also be incorrect. Instead of solving problems and ending suffering, one will create more suffering, accumulate problems, and increase trouble.

Right view can be separated into two levels:

-

First, those kinds of views, thoughts, opinions, beliefs, preferences, and values which are connected to an awareness of one’s actions and the effects of such actions, or which foster a sense of personal accountability. One sees things correctly in the light of Dhamma teachings. The precise term for this kind of view is ’knowledge of being an owner of one’s deeds’ (kammassakatā-ñāṇa). It is mundane right view (lokiya-sammādiṭṭhi) and pertains to the level of moral conduct.

-

Second, those views and ways of thinking which help to discern how all conditioned things exist in accord with the law of causality. It is an understanding of things according to how they really are. One is not biased by preferences and aversions or swayed by how one wants things to be or not be. It is a knowledge in harmony with natural truth and is technically referred to as ’knowledge consistent with truth’ (saccānulomika-ñāṇa). It is right view aligned with transcendent understanding and pertains to the level of absolute truth.

Likewise, there are two kinds of wrong view (micchā-diṭṭhi): those views, notions, and values which deny a sense of personal accountability – a refusal to admit one’s own responsibility; and an ignorance of the world as it really is – the formation of deluded images according to how one personally wants the world to be. {611}

In any case, the internal spiritual training of an individual begins with and continues as a result of an engagement with his or her external environment; it is dependent on external influences which act as a source of motivation or as conditioning factors. If one receives teachings, advice, and transmissions from correct sources, or if one is able to select, discern, contemplate and engage with things properly, right view (sammā-diṭṭhi) will arise and true training will ensue.

Conversely, if one receives incorrect teachings, advice and transmissions, or if one in unable to reflect on, consider, and gain insight into one’s experiences, wrong view (micchā-diṭṭhi) will arise and one will train incorrectly or not train at all.

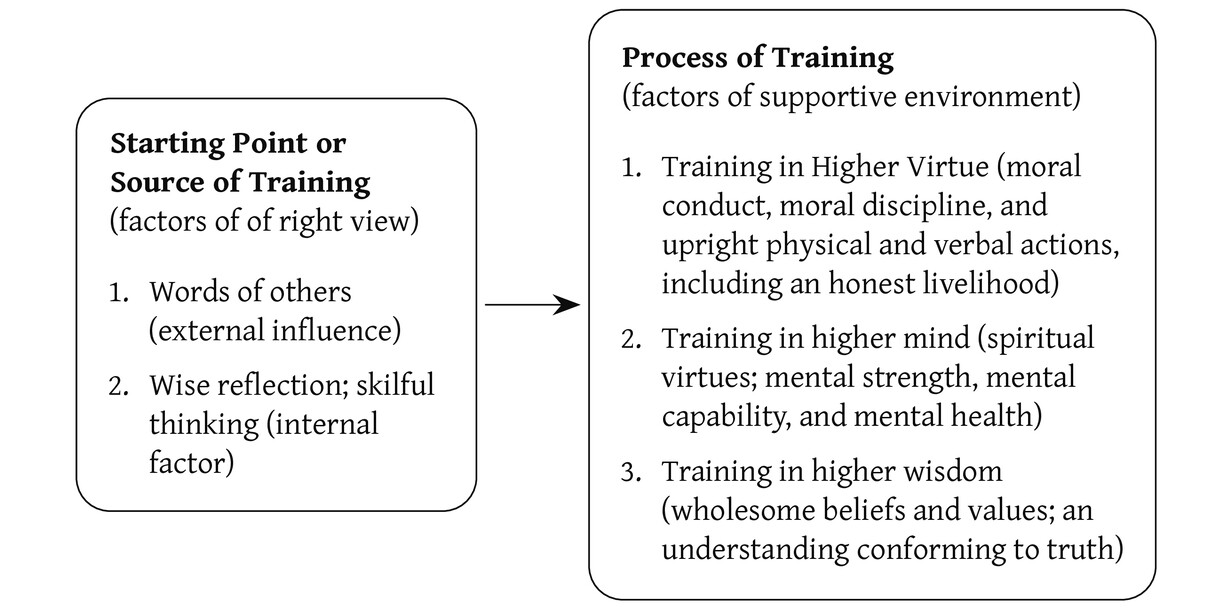

To review, there are two basic sources of spiritual training, which are called the ’prerequisites of right view’:

-

The external factor of the instruction of others (paratoghosa): the words or utterance of others. This refers to social influences and transmissions, for example from parents, teachers, friends, associates, books, the media, and one’s culture. These outside influences provide correct information and teachings and they encourage one to go in a wholesome direction.

-

The internal factor of wise reflection (yoniso-manasikāra): to be skilled at reflection; to apply proper methods of thinking and reasoning.

Similarly, there are two sources to wrong training or to a lack of spiritual training, which are the prerequisites of wrong view: incorrect, unwholesome instruction by others and an absence of wise reflection – an inability to reflect wisely.

Process of Training

As mentioned above, the essence of spiritual training is right view. When right view is firmly established, spiritual training proceeds effectively.

This process is divided into three major stages, which collectively are referred to as the three trainings or the threefold training:

-

Training in higher virtue (adhisīla-sikkhā): training in the area of conduct, moral discipline, and uprightness in physical actions, speech, and livelihood. It can be simply referred to as ’virtue’ (sīla).

-

Training in higher mind (adhicitta-sikkhā): the training of the mind, the cultivation of spiritual qualities, and the development of mental strength, mental aptitude, and mental health. It can be simply referred to as ’concentration’ or ’mental collectedness’ (samādhi).

-

Training in higher wisdom (adhipaññā-sikkhā): the development of wisdom, giving rise to a knowledge of things as they truly are, a discernment of the causal nature of things, which enables one to solve problems in line with cause and effect; a thorough understanding of phenomena, to the extent that one is able to liberate the mind from all clinging and attachment, eliminate mental defilement, and bring an end to suffering – to live with a mind that is free, pure, joyous and bright. It can be simply referred to as ’wisdom’ (paññā).

The formulation of these three trainings is directly connected to the teaching referred to as the Noble Path (ariya-magga): the ’supreme way’, the ’noble method for solving problems belonging to the noble ones’, or the ’path leading to the cessation of suffering and to the state of awakening’.

The Noble Path contains eight essential factors or eight aspects of practice:

-

Right view (sammā-diṭṭhi): correct views, ideas, opinions, beliefs, attitudes and values; to see things according to causes and conditions; to see things in harmony with truth or with reality. {612}

-

Right thought (sammā-saṅkappa): thoughts, considerations, and motives which do not harm oneself or others, are not corrupted by defilement, and are conducive to wellbeing and happiness, for example: thoughts of renunciation, well-wishing, kindness, and benefaction; pure, truthful and righteous thoughts; thoughts free from selfishness, covetousness, anger, hatred, and malice.

-

Right speech (sammā-vācā): honest and upright speech; speech that is not abusive, deceitful, divisive, slanderous, coarse, trivial, or pointless; speech that is polite and gentle, promoting friendship and harmony; rational, beneficial speech.

-

Right action (sammā-kammanta): righteous, beneficial actions; non-oppressive, non-harmful actions; actions that build good relationships, promote cooperation, and lead to a peaceful society. Specifically, this refers to actions that are not involved in or contributive to killing or physical injury, to violating the belongings of others, or to violating the rights of others in regard to their spouse or cherished items and people.

-

Right livelihood (sammā-ājīva): earning a living in righteous ways, which do not cause trouble or harm to others.

-

Right effort (sammā-vāyāma): righteous effort, that is: to strive to prevent and avoid unarisen evil, unwholesome qualities; to strive to abandon and eliminate arisen evil, unwholesome qualities; to strive to establish and foster unarisen wholesome qualities; and to strive to cultivate, increase, and perfect arisen wholesome qualities.

-

Right mindfulness (sammā-sati): to be vigilant and attentive; to sustain attention on whichever necessary task one faces in the moment; to be circumspect about one’s activities; to recollect those virtuous, supportive, or required factors connected to a specific activity; to not be absentminded, careless, or negligent. Most notably, this refers to mindfulness fully attentive to one’s own physical activities, feelings, state of mind, and thoughts. One does not allow alluring or annoying sense impressions to lead one astray or to cause confusion.

-

Right concentration (sammā-samādhi): firmly established attention; the mind is focused on an activity or on an object of attention (ārammaṇa); the mind is one-pointed, calm, relaxed, pure, bright, and strong; it is malleable and engaged, ready for the effective application of wisdom; it is not distracted, disturbed, confused, stressed, rigid, or despondent.

The threefold training is designed to bear fruit according to the principles of practice inherent in the Noble Eightfold Path. This training generates and develops the eight Path factors. A Dhamma practitioner makes full use of these Path factors and gradually solves problems until he or she reaches the complete end of suffering. The relationship between the threefold training and the Eightfold Path is as follows:

-

Training in higher virtue: aspects of training giving rise to right speech, right action, and right livelihood. These three Path factors are cultivated to the point where one reaches the standard of a noble being in regard to moral conduct, discipline, and skilful social interaction. This is the basis for developing the power of mind.

-

Training in higher mind: aspects of training giving rise to right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. These three Path factors are cultivated to the point where one reaches the standard of a noble being in regard to spiritual qualities, power of mind, mental capability, and mental health. This is the basis for developing wisdom. {613}

-

Training in higher wisdom: aspects of training giving rise to right view and right thought. These two Path factors are cultivated to the point where one reaches the standard of a noble being in regard to wisdom. One’s mind is bright, joyous, and freed from all forms of grasping and affliction; one reaches true deliverance of mind by way of wisdom.

As mentioned above, right view – the mainstay of spiritual training – arises dependent on two factors (the prerequisites of right view), which are the source, origin and starting point of practice. Therefore, in the activities pertaining to spiritual training special emphasis should be given to these two factors. Indeed, the expression ’providing training’ relates precisely to these two factors. As for the three stages of training – sīla, samādhi, and paññā – they are used simply as reference points for creating a supportive environment and for ensuring that the direction of practice proceeds according to proper principles.

Based on this understanding one is able to outline spiritual training as shown on Figure Outline of Spiritual Training.

Basic Elements of Spiritual Training

From the above section we see that thinking or reflection comprises one of the two initial factors or sources of spiritual training. To gain a clear understanding of the vital role of thought, however, it should be explained in conjunction with the second factor, of the teachings by others:

Monks, there are these two conditions giving rise to right view: the words of others and wise reflection.1 {614}

A. I. 88.

In reference to external factors, I know not of any other single factor so conducive to great benefit as having a virtuous friend.

In reference to internal factors, I know not of any other single factor so conducive to great benefit as wise reflection.

A. I. 17.

These two prerequisites of right view can also be called the forerunners to spiritual training. They are the wellspring of right view, which is the starting point and key principle of spiritual practice in its entirety. Let us review these factors in more depth:

-

The words of others (paratoghosa): external motivation and influence; teachings, advice, instruction, transmission, schooling, proclamations, information, and news coming from external sources. This also includes imitating or emulating others’ behaviour and ideas. It is an external or social factor.

Examples of such sources of learning include: one’s parents, teachers, mentors, friends, companions, co-workers, bosses, and employees; famous and esteemed people; books, other forms of media, and religious and cultural institutions. In this context, it refers specifically to those external influences leading one in a correct, wholesome direction and providing correct knowledge, and in particular those enabling one to attain the second factor of wise reflection.

A person with suitable attributes and qualities, who is able to perform the function of instruction well, is called a virtuous friend (kalyāṇamitta). Generally speaking, for a virtuous friend to act effectively and succeed in instructing others, he or she must be able to instil confidence in the student or practitioner, and therefore the method of learning here is referred to as the ’way of faith’.

If the persons offering instruction, for example parents or teachers, are unable to establish a sense of trust in the pupil (or child, as the case may be), who subsequently develops greater interest and trust in another source of information and thinking, say in the words of a movie star transmitted via the media, and if this alternative information is bad or wrong, the process of learning or training is beset by danger. The end result may be a wrong form of learning or an absence of true learning.

-

Wise reflection (yoniso-manasikāra); skilful modes of thinking; systematic thinking; the ability to contemplate and discern things according to how they truly exist, for example the recognition that a specific phenomenon ’exist just so’. One searches for causes and conditions, inquires into the source of things, traces the complete sequence of events, and analyzes things in order to see things as they are and as conforming to the law of causality. One does not attach to or distort things out of personal craving and clinging. Wise reflection leads to wellbeing and an ability to solve problems. This is an internal, spiritual factor and may be referred to as the ’way of wisdom’.

Of these two factors, wise reflection is essential and indispensable. Spiritual training truly bears fruit and its goal is reached as a result of wise reflection. Indeed, it is possible for wise reflection to initiate spiritual training without the assistance of external influences. If one relies on the first factor of external instruction, it must lead to wise reflection for one’s training to reach completion. Intuition, insight, and the discovery and realization of truth is accomplished by way of wise reflection. {615}

Having said this, one should not underestimate the power of the first factor, of the instruction by others, because only a minute number of individuals do not need to rely on this factor – those who can progress solely by the application of wise reflection. These individuals, like the Buddha, are exceptional. Almost everyone in the world relies on the instruction by others to help show the way.

All forms of formal and systematic education, both in the past and in the present, and all forms of schooling in the field of the arts and sciences are matters pertaining to this factor of the ’words of others’ (paratoghosa). The wholesome transmission of knowledge by way of virtuous friends thus deserves the utmost care and attention.

A point that needs to be reiterated here is that in providing an education or skilful instruction, a virtuous friend needs to constantly keep in mind that this instruction must act as a catalyst for the arising of wise reflection in the students.

Thinking Conducive to Spiritual Training

Thinking is linked to and follows cognition. The process of cognition begins at the point where a sense base (āyatana) encounters a sense object (ārammaṇa). At this point consciousness arises (viññāṇa) – the awareness of a sense object – for example seeing a form, hearing a sound, or knowing a mental object. When this process is complete it is called ’cognition’, or literally, according to the Pali, as ’contact’ (phassa).

With cognition there arises some form of sensation (vedanā), say of pleasure and ease, suffering and discomfort, or a neutral feeling.2 At the same time, there arises perception (saññā) – the naming, designation, or recognition of the sense object. From here there follows thinking (vitakka) – thoughts, reflections and deliberations.

This process of cognition is the same, regardless of whether one encounters and experiences something externally, or whether one thinks of something and contemplates it in the mind.

Using the act of seeing as an example, this process can be illustrated as follows (similar to earlier at Figure The Cognitive Process (Simple Form) in Chapter 2. Six Senses).

Eye (āyatana) +

physical form (ārammaṇa) +

seeing (cakkhu-viññāṇa) =

contact (phassa) →

sensation (vedanā) →

perception (saññā) →

thinking (vitakka)

The act of thinking plays a very important role in determining a person’s personality and way of life, as well as shaping society as a whole. Thinking, therefore, is an essential factor in spiritual training. Thinking, however, is itself determined by various factors and conditions.

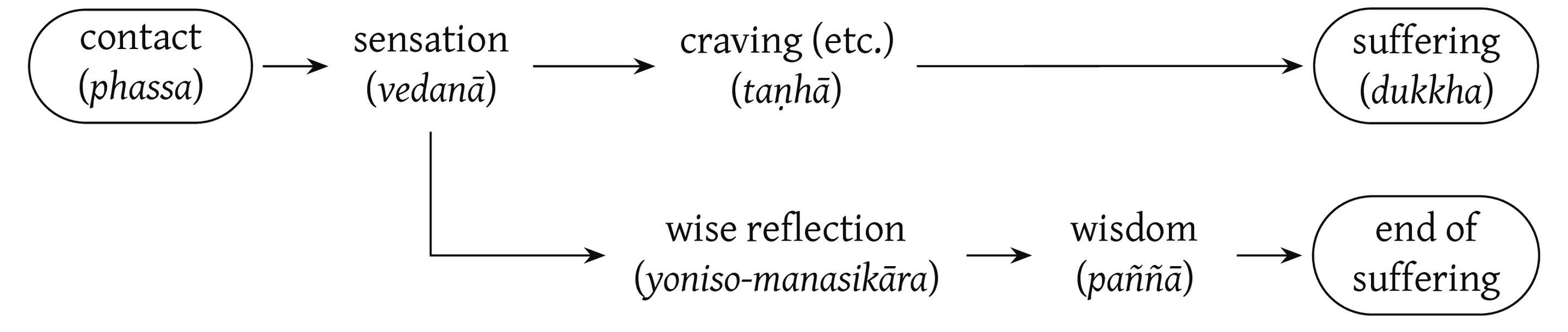

One factor which exerts a powerful influence on thinking is sensation (vedanā), in particular the feelings of pleasure and pain.

Ordinarily, when people contact sense impressions and experience feelings, unless other factors enter to correct or intercept the process, these feelings determine the way a person thinks:

-

If the feelings are pleasurable or comforting one delights in them; one wishes to acquire or consume the object (this is craving – taṇhā – in an affirmative sense).

-

If the feelings are painful or oppressive one is averse to them; one wishes to escape from or eliminate the object (this is craving in an adversative sense). {616}

At this point a person creates elaborate thoughts and ideas about the sense object acting as the source of that feeling. The object becomes the focus of a person’s thinking, accompanied by saññā – memories and perceptions of this object. These proliferations of thought follow the course of the person’s likes and aversions. The determining factors for thought are a person’s accumulated proclivities, prejudices, habits, disposition, and mental defilements (collectively referred to as mental formations – saṅkhāra). He or she thinks within the confines and limitations and along the line of these mental formations. Expressions of speech and physical actions may then follow in the wake of these thoughts.

Even if these thoughts are not expressed as outward actions, they still have an impact on a person’s mind. They limit and constrict the mind and create various forms of mental distress, agitation, disturbance, depression, and confusion. Thoughts related to specific subjects can create mental bias and distortion, resulting in a failure to see things according to the truth, while some thoughts may be tainted by greed or hostility.

In the case that one experiences neutral sensations – neither pleasurable nor painful – if one is not skilled at reflection and allows oneself to remain under their influence, one’s thinking will be aimless and incoherent or completely stifled. This is an unfavourable and unwholesome situation, leading to problems and greater suffering.

The main factors of this process can be illustrated thus:

Contact (phassa) →

sensation (vedanā) →

craving, both affirmative and adversative (taṇhā) →

suffering (dukkha)

For most people this process of compounding problems occurs almost continually. In a single day it may occur repeatedly and countlessly. The life of a person lacking spiritual training tends to be dominated and determined by this way of thinking. It requires no intelligence, understanding, or special capability. It is the most basic way in which a human being operates. And the more a person has accumulated the habit of thinking in this way, the easier this process unfolds automatically, as if stuck in a pre-established rut.

Because this process functions without any guidance by mindfulness and wisdom, it generates ignorance (avijjā). Rather than being conducive to solving problems, it creates more problems and increases suffering. It is antithetical to spiritual training. Technically, it is thus referred to as the ’mode of conditionality leading to suffering’.

The basic attribute of this way of thinking is that it serves to gratify craving. In sum it can be referred to as the ’process of thinking that panders to craving’, ’thinking that causes problems’, or simply as the ’cycle of suffering’.

The beginning of spiritual training begins with the application of mindfulness and wisdom. Here, a person no longer allows this aforementioned process of thinking or mode of conditionality to function unabated and unchecked. One uses mindfulness, wisdom, and other spiritual factors to interrupt or reduce the flow of this way of thinking, resulting in a severance of the cycle or a transformation and altered course of thinking. One begins to be liberated – to no longer be enslaved by this process of thinking. {617}

At first, an altered course of thinking may result from views or traditional ways of thinking transmitted by external sources, say by other people or social institutions, to which one adheres out of faith. Generally speaking the most such external instruction can do is to deter or restrain one from blindly following a course of thinking pandering to craving, or perhaps it can provide one with an alternative fixed pattern of thinking. But it does not necessarily lead to a progressive, independent way of thinking. If the instruction is exceptional, however, it can generate the kind of faith that leads people to think for themselves.

An example of instruction that leads to a strictly prescribed, unyielding form of faith, and is not a vehicle for further contemplation, is to have others believe that everything in the world is governed and controlled by some divine being or occurs randomly or by accident. If one believes in such teachings, all one has to do is wait for the will of God or leave everything up to fate. One need not investigate or reflect on things.

Conversely, an example of instruction that generates a kind of faith leading to contemplation is to have others believe that all things exist according causes and conditions. If one believes this then no matter what happens one will investigate and probe into the underlying causes and conditions, and one will develop an increased knowledge and understanding.

Wholesome thinking and contemplation induced by a faith in external instruction begins with wise reflection (yoniso-manasikāra). In other words, skilful instruction generates a faith leading to wise reflection.

With the arising of wise reflection, spiritual training has begun. From this point a person applies and develops wisdom, which helps to solve problems and is the path to the cessation of suffering. In a nutshell, thinking that supports and promotes wisdom is spiritual training.

Wise reflection plays an especially important role by preventing feeling (vedanā) from producing craving (taṇhā). When one applies wise reflection, one experiences feeling but without it leading to craving. And when there is no craving, one does not create fanciful ideas (’mental proliferation’) subject to the power of craving.

When one severs thinking processes pandering to craving, skilful, systematic reflection leads to the path of wisdom development and to the end of suffering. The two kinds of thinking can be illustrated as shown on Figure Two Kinds of Thinking.

In any case, for ordinary people, even if they have begun a spiritual training, these two ways of thinking arise alternately, and one way of thinking may interfere with the other. For example, the first process may unfold until it reaches craving, but then wise reflection steps in to cut off the process and steer it in a new direction. Or the latter process may reach the stage of wisdom, yet craving in a new guise hijacks the process. It can thus occur that the fruits of wisdom are corrupted to serve the interests of craving. {618}

When those persons who have completed spiritual training think, they apply analytical reflection (yoniso-manasikāra). When they are not thinking they abide mindfully in the present moment, that is, they are attentive to those activities in which they are engaged.

To say that one applies analytical reflection when one thinks also implies that one applies mindfulness (sati), because wise reflection is a source of nourishment for mindfulness. When thinking proceeds in a systematic, purposeful way, attention does not stray or drift aimlessly. Mindfulness then functions to keep attention on the tasks at hand.

Analytical reflection is thus a key factor in spiritual training, connected to the essential stage of wisdom development. It is required for living a virtuous life, helping to solve problems and acting as a refuge for people.

In the gradual process of wisdom development, wise reflection is part of a stage beyond faith, because at this stage a person begins to think independently from others.

Within the system of spiritual training, wise reflection is an internal factor, connected to the development and application of thought. It can be defined as a proper method of thinking, methodical thinking, or analytical thinking, and it has the following attributes: it prevents one from looking at things superficially; it leads to self-reliance; and it leads to liberation, freedom from suffering, true peace, and pure wisdom, which are the highest goals of Buddhism.

The preceding material has presented a general introduction to the two initial factors of spiritual training: the utterances of others (paratoghosa), which can also be described as having a virtuous friend (kalyāṇamitta), which is an external factor and a matter dealing with faith; and wise reflection (yoniso-manasikāra), which is an internal factor and a matter dealing with wisdom.

From here on in this chapter the focus will be solely on wise reflection, to elucidate the methods of thinking distinctive to Buddha-Dhamma. {619}

Importance of Wise Reflection

Monks, just as the dawn is the forerunner and precursor of the rising of the sun, so too, the fulfilment of wise reflection (yoniso-manasikāra) is the forerunner and precursor for the arising of the Noble Eightfold Path for a monk. It is to be expected of a monk who has brought wise reflection to completion that he will develop and cultivate the Noble Eightfold Path.

S. V. 31.

Monks, just as the dawn’s silver and golden light is the precursor to the rising of the sun, so too, for a monk wise reflection is the forerunner and precursor for the arising of the seven factors of enlightenment. When a monk is accomplished in wise reflection, it is to be expected that he will develop and cultivate the seven factors of enlightenment.

S. V. 79.

Monks, just as this body is sustained by nutriment, subsists in dependence on nutriment, and cannot subsist without nutriment, so too the five hindrances are sustained by nutriment, subsist in dependence on nutriment, and cannot subsist without nutriment. And what is [their] nutriment?: … a frequent lack of wise reflection….

Monks, just as this body is sustained by nutriment, subsists in dependence on nutriment, and cannot subsist without nutriment, so too the seven factors of enlightenment are sustained by nutriment, subsist in dependence on nutriment, and cannot subsist without nutriment. And what is [their] nutriment?: … a repeated application of wise reflection.3

S. V. 64-7.

Monks, by careful attention (yoniso-manasikāra), by careful right striving (yoniso-sammappadhāna), I arrived at unsurpassed liberation, I realized unsurpassed liberation. You too, by careful attention, by careful right striving, shall arrive at unsurpassed liberation, shall realize unsurpassed liberation. {620}

Vin. I. 23; S. I. 105.

Monks, I say that the destruction of the taints is for one who knows and sees, not for one who does not know and see. Who knows and sees what? Wise attention and unwise attention.4 When one attends unwisely, unarisen taints arise and arisen taints increase. When one attends wisely, unarisen taints do not arise and arisen taints are abandoned.

M. I. 7.

Monks, whatever states there are that are wholesome, partaking of the wholesome, pertaining to the wholesome, they are all rooted in wise reflection, converge upon wise reflection, and wise reflection is declared to be the chief among them.

S. V. 91.

See here, Mahāli, greed … hatred … delusion … unwise reflection … wrongly directed attention is the cause, the condition, for evil actions, for the existence of evil. Non-greed … non-hatred … non-delusion … wise reflection … rightly directed attention is the cause, the condition, for virtuous actions, for the existence of virtuous actions.

A. V. 86-7.

No other thing do I know which is so responsible for causing unarisen wholesome states to arise and arisen unwholesome states to wane as wise reflection. In one who reflects wisely wholesome states not yet arisen will arise and unwholesome states that have arisen will wane.

A. I. 13.

No other thing do I know which is so conducive to great benefit …

A. I. 16.

… which is so conducive for the stability, non-decline, and non-disappearance of the true Dhamma as wise reflection.

A. I. 18.

In regard to internal factors, no other thing do I know which is so conducive to great benefit as wise reflection.

A. I. 17; cf.: S. V. 101.

For a monk who is still in training, who has not yet realized the fruit of arahantship, and who aspires to the unsurpassed security from bondage I do not see any other internal factor that is so helpful as wise reflection. A monk who applies wise reflection is able to eliminate the unwholesome and to cultivate the wholesome.

It. 9-10.

I do not see any other thing so conducive for generating unarisen right view or for increasing arisen right view as wise reflection. In one who reflects wisely unarisen right view will arise and arisen right view will increase.

A. I. 31.

I do not see any other thing so conducive for generating unarisen enlightenment factors or for bringing arisen enlightenment factors to completion as wise reflection. In one who reflects wisely unarisen enlightenment factors will arise and arisen enlightenment factors will be brought to completion. {621}

A. I. 14-15.

No other thing do I know on account of which unarisen doubt does not arise and arisen doubt is abandoned as much as on account of wise attention.

A. I. 4-5.

For one who attends properly to signs of impurity, unarisen lust will not arise and arisen lust will be abandoned…. For one who attends properly to the liberation of the mind by lovingkindness, unarisen hatred will not arise and arisen hatred will be abandoned…. For one who attends properly to [all] things, unarisen delusion will not arise and arisen delusion will be abandoned.

A. I. 201.

When one attends wisely, unarisen sensual desire … ill-will … sloth and torpor … restlessness and worry … doubt does not arise and arisen sensual desire … doubt is abandoned. At the same time the unarisen enlightenment factor of mindfulness … the unarisen enlightenment factor of equanimity arises and the arisen enlightenment factor of mindfulness … equanimity comes to fulfilment.

S. V. 85.

There are nine things that are greatly supportive and which are rooted in wise reflection: when one possesses wise reflection, joy arises; when one is joyful, delight arises; when one experiences delight, the body is relaxed and tranquil; when the body is relaxed, one experiences happiness; for one who is happy, the mind is concentrated; when the mind is concentrated, one knows and sees according to the truth; when one knows and sees according to the truth, one becomes disenchanted; with disenchantment one becomes dispassionate; by dispassion one is liberated.

D. III. 288.

Definition of Wise Reflection

The compound term yoniso-manasikāra is made up of the two words yoniso and manasikāra.

Yoniso is derived from the word yoni (’origin’, ’place of birth’, ’womb’) and is variously translated as ’cause’, ’root’, ’source’, ’wisdom’, ’method’, ’means’, or ’path’. (See Note Yoniso: A Means and a Path)

Manasikāra is translated as ’mental activity’, ’thinking’, ’consideration’, ’reflection’, ’directing attention’, or ’contemplation’. (See Note Synonyms of Manasikāra)

As a compound the term yoniso-manasikāra is traditionally defined as ’skilfully directing attention’. The commentaries and sub-commentaries elaborate on this definition and explain the nuances of this term by presenting various synonyms, as follows:5

-

Upāya-manasikāra: ’methodical reflection’; to think or reflect by using proper means or methods; systematic thinking. This refers to methodical thinking that enables one to realize and exist in harmony with the truth, and to penetrate the nature and characteristics of all phenomena. {622}

-

Patha-manasikāra: ’suitable reflection’; to think following a distinct course or in a proper way; to think sequentially and in order; to think systematically. This refers to thinking in a well-organized way, e.g. in line with cause and effect; to not think in a confused, disorderly way; to not at one moment be preoccupied by one thing and then in the next moment jump to something else, unable to sustain a precise, well-defined sequence of thought. This factor also includes the ability to guide thinking in a correct direction.

-

Kāraṇa-manasikāra: ’reasoned thinking’; analytical thinking; investigative thinking; rational thinking. This refers to inquiry into the relationship and sequence of causes and conditions; to contemplate and search for the original causes of things, in order to arrive at their root or source, which has resulted in a gradual chain of events.

-

Uppādaka-manasikāra: ’effective thinking’; to apply thinking in a purposeful way, in order to yield desired results. This refers to thinking and reflection that generates wholesome qualities, e.g.: thoughts that rouse effort; an ability to think in a way that dispels fear and anger; and contemplations which support mindfulness or which strengthen and stabilize the mind.

Yoniso is most often defined in the commentaries solely as upāya (’means’, ’method’): MA. V. 81; SA. I. 88; AA. I. 51; AA. II. 38; AA. IV. 1; KhA. 229; NdA. II. 343; DhsA. 402; VismṬ.: Sīlaniddesavaṇṇanā, Paccayasannissitasīlavaṇṇanā; VismṬ.: Anussatikammaṭṭhānaniddesavaṇṇanā, Maraṇassatikathāvaṇṇanā.

It is defined as both upāya and patha (’path’) at: [AA. 2/157]; AA. III. 394; ItA. I. 62; NdA. II. 463; Vism. 30. It is defined as upāya, patha and kāraṇa (’means’, ’doing’) at: DA. II. 643. It is defined as kāraṇa at SA. II. 268, 321; [SA. 3/390]. It is defined as paññā in the Nettipakaraṇa (see the Nettipakaraṇa; see also the later text the Abhidhānappadīpikā: verse 153).

Noteworthy synonyms for manasikāra include:

āvajjanā: paying attention, adverting the mind;

ābhoga: ideation, thought;

samannāhāra: consideration, reflection; and

paccavekkhaṇa: consideration, reflection, reviewing.

See: DA. II. 643; MA. I. 64; ItA. I. 62; Vism. 274.

There are many other synonyms, including:

upparikkhā: examination, investigation (S. III. 42, 140-41);

paṭisaṅkhā: reflection, consideration (A. II. 39-40);

paṭisañcikkhaṇā: thinking over, reflection (A. V. 184); this term is equated with yoniso-manasikāra at: S. II. 70 and S. V. 389;

parivīmaṁsā: thorough consideration, examination (S. II. 81).

The term sammā-manasikāra (D. I. 12-13; D. III. 30; DA. I. 104; DA. III. 888; MA. I. 197) has a meaning very close to that of yoniso-manasikāra, but it is seldom used and its meaning is not considered to be strictly defined.

These four definitions describe various attributes of the kind of thought referred to as ’wise reflection’ (yoniso-manasikāra). At any one time, wise reflection may contain all or some of these attributes. These four definitions may be summarized in brief as ’methodical thinking’, ’systematic thinking’, ’analytical thinking’, or ’thinking inducing wholesomeness’. It is challenging, however, to come up with a single definition or translation for yoniso-manasikāra. Most translations will only capture limited nuances of this term and are not comprehensive. The alternative is to give a lengthy definition, as presented above.

The difficulty of translating this term notwithstanding, there are prominent attributes of this way of thinking which can be used to represent all the other attributes and which can be translated in brief, for example: ’methodical thinking’, ’skilful thinking’, ’analytical thinking’, and ’investigative thinking’. Once one has gained a thorough understanding of this Pali term, it is convenient to rely on a concise translation like ’wise reflection’, ’systematic reflection’, or ’careful attention’. (See Note Traslation of Yoniso Manasikāra)

Traslation of Yoniso Manasikāra

There are many English translations for yoniso-manasikāra, some of them literal translations, e.g.: proper mind-work, proper attention, systematic attention, reasoned attention, attentive consideration, reasoned consideration, considered attention, careful consideration, careful attention, ordered thinking, orderly reasoning, genetical reflection, critical reflection, analytical reflection, etc. [Trans.: in this text, when encountering the terms ’wise reflection’ and ’systematic reflection’, know that I am referring to yoniso-manasikāra.]

Earlier, I mentioned the relationship between the internal factor of wise reflection and the external factor of instruction by others or virtuous friends. Here, let us focus more closely on how a virtuous friend, by relying on the principle of faith, can help those people who are unskilled at thinking for themselves and applying wise reflection.

In respect to the first three attributes of wise reflection described above, virtuous friends are only able to point out or throw light on specific truths, but practitioners must contemplate and gain understanding by themselves. When it comes to the stage of true understanding, faith is inadequate.6 In regard to these three attributes, faith is thus extremely limited. {623}

In respect to the fourth attribute (reflection generating wholesome qualities), however, faith plays a powerful role. For example, some people are weak and easily daunted or think in irrational and harmful ways. If a virtuous friend is able to establish faith in such people, this will be very helpful for them. He or she may inspire and encourage them by using skilful means. Having said this, there are some people who are naturally endowed with wise reflection and are able to think for themselves. In discouraging or distressing situations they are able to effectively motivate themselves and think of ways to address the problem.

On the contrary, if one has evil friends or applies unwise attention, despite finding oneself in good circumstances and encountering good things, one is likely to think or act in bad ways. For instance, when discovering a pleasant, secluded place, a bad person may think of it as a suitable place to commit a crime. In a similar vein, some people are highly suspicious – when they see someone else smile, they think that they are being ridiculed or insulted.

If one allows this course of thinking to proceed unimpeded, unwise attention will nourish and strengthen such unwholesome states of mind. For example, a person who habitually sees things in a negative light will begin to see others as adversaries. Similarly, a person who is habitually afraid and sees others as thinking ill of him may develop a mental disorder of paranoia.7

Depending on either wise reflection or unwise reflection, the same subject matter may result in very different behaviour for different people. For example, one person may think of death with improper attention and consequently experience fear, depression, apathy, or confusion. Another person may think of death with wise reflection and thus appreciate the need to abstain from unwholesome actions. He or she will be calm, heedful, and ardent, hastening to perform good deeds.8

In terms of insight into reality, wise reflection is not wisdom itself, but rather a condition for the arising of wisdom, that is, wise reflection generates right view. The Milindapañhā describes the difference between reflection and wisdom thus:9

-

First, animals such as goats, sheep, cows, buffalo, camels, and donkeys possess a form of reflection (manasikāra – ’mental application’), but they do not possess wisdom (nor is their reflection ’analytical’ – yoniso).

-

Second, manasikāra has the characteristic of contemplation and reflection, whereas wisdom (paññā) has the characteristic of severing. Manasikāra gathers together and submits ideas to wisdom, which is then able to eliminate mental defilement, similar to a man grasping an ear of rice by his left hand, enabling him to successfully harvest it with a sickle held in his right hand.

Based on this interpretation, yoniso-manasikāra is a kind of mental engagement (manasikāra) leading to an application and development of wisdom.10 {624}

The Papañcasūdanī states that unwise attention (ayoniso-manasikāra) is the root source of the round of rebirth (vaṭṭa), causing beings to accumulate problems and to swim around in suffering. This text also explains that, when it is allowed to prosper, unwise attention increases both ignorance (avijjā) and the craving for becoming (bhava-taṇhā). With the arising of ignorance the cycle of Dependent Origination begins, starting with ignorance acting as the condition for volitional formations (saṅkhāra), and completed with the arising of the whole mass of suffering. The beginning of the cycle of Dependent Origination can also be designated by the arising of craving (taṇhā), starting with craving acting as a condition for grasping, and similarly completed with the mass of suffering.

Conversely, wise reflection is the root cause for the cycle of ’turning away’ (vivaṭṭa), enabling one to escape from the whirlpool of suffering and to truly solve problems. With the arising of wise reflection a person begins to practise according to the Eightfold Path, with right view as the leading factor. Right view here is equivalent to true knowledge (vijjā). With the arising of true knowledge, ignorance ceases. With the end of ignorance the cessation cycle (nirodha-vāra) of Dependent Origination is set in operation, leading gradually to the cessation of suffering.11 These processes can be illustrated thus:

Round of rebirth (vaṭṭa):

Unwise reflection (ayoniso-manasikāra):

Ignorance (avijjā) →

volitional formations (saṅkhāra) …

aging, death, sorrow, lamentation =

the arising of suffering.Craving (taṇhā) →

grasping (upādāna) …

aging, death, sorrow, lamentation =

the arising of suffering.

Cycle of ’turning away’ (vivaṭṭa):

Wise reflection (yoniso-manasikāra) →

cultivation of the Path (magga-bhāvanā):

right view (sammā-diṭṭhi) =

true knowledge (vijjā) →

the cessation of ignorance →

the cessation of volitional formations …

the cessation of suffering.

The term yoniso-manasikāra has a wide range of meaning, including thinking concerned with moral issues and thinking in line with virtuous and truthful principles which one has studied and understood. Basic levels of contemplation which do not require a profound degree of wisdom include: thoughts of amicability, thoughts of lovingkindness, thoughts of generosity and assistance, and thoughts of generating inner strength, determination, and courage. Some contemplations, however, require refined and subtle degrees of wisdom, for example an analysis of subsidiary factors or an investigation into causes and conditions.

Because the meaning of wise reflection is so comprehensive, everyone is capable of applying it, especially elementary levels of contemplation. All people need to do is direct their course of thinking in a wholesome direction, corresponding to teachings they have received and ideas they have nurtured. This basic form of wise reflection helps to generate mundane right view and is greatly influenced by faith, which comes about through the words of others (paratoghosa), including one’s education, culture, and the presence of virtuous friends. Faith acts as an anchor for the mind and an internal force. When a person cognizes a sense object or encounters a particular situation, the course of his or her thinking is directed by the force of faith, as if faith has already dug a channel for thinking to go. {625}

For this reason the Buddha stated that (correct) faith is the nourishment for wise reflection.12 External instruction from virtuous friends, which uses faith as a channel, is able to gradually increase understanding and introduce a person to new ideas, for example by way of consultation and by asking questions to clear up doubts.

When it is applied repeatedly and nourished by faith, proper reflection develops and becomes more agile, deepening wisdom. When one contemplates and sees that the teachings one has received are truly correct and beneficial, one becomes more confident and faith increases. In this way, wise reflection enhances faith.13 It urges people to make greater effort in their studies, until eventually their own reflections lead them to realization and deliverance.

Here, a person’s spiritual practice relies on an integration between internal and external factors. Wholesome influence from external sources is implied in the phrase: ’Be your own refuge, with no one else as your refuge.’14 The Buddha did not reject external influences. Indeed, external influences and the quality of faith are extremely important, but the key determining factor lies within, that is, wise reflection.

The more one is able to apply wise reflection, the less one relies on external factors. Similarly, if someone does not apply wise reflection at all, any amount of help from virtuous friends is in vain.

As most students of Buddhism know, mindfulness (sati) is a vital factor that is required for every activity. The problem arises, however, of how to establish mindfulness in time and, once it is established, how to sustain it in a consistent, continuous way so that it is not broken and does not slip away.

In this context, there are teachings which explain how wise reflection nourishes mindfulness, assisting the establishment and the uninterrupted flow of mindfulness.15

If one possesses systematic, coherent, and effective reflection, one is able to sustain mindfulness consistently. If one is unable to reflect properly, however, or if one’s thinking is ineffectual or aimless, mindfulness will keep slipping away and one will be unable to sustain it. It is neither correct nor possible to truly compel or constrain mindfulness. The correct course is to nourish mindfulness and to generate its supportive conditions. If these conditions are present, mindfulness arises – this is part of a natural process. One thus needs to act in accord with this process.

The function of wise reflection is to cut off ignorance and craving (or in an affirmative sense, it summons wisdom and wholesome qualities).

Generally speaking, when a person encounters a sense object, the process of thinking begins immediately. At this point two distinct forces vie with one another:

-

If ignorance and craving are able to seize control of thinking, the thought process will be subject to these factors and shaped by mental formations based on likes and dislikes and on pre-established concepts and ideas.

-

If wise reflection is able to bar and cut off ignorance and craving, it will lead thinking in a correct direction, resulting in a thought process free from these negative factors. The corrupted thought process is replaced by the process of knowing and seeing (ñāṇa-dassana) or of true knowledge and liberation (vijjā-vimutti). {626}

Generally speaking, when ordinary, unawakened beings encounter a sense object, their thinking follows the course of ignorance and craving. They overlay the experience with their likes and dislikes, or with their pre-established ideas. This is the point at which thoughts connected to that experience or sense object begin to be shaped and moulded by ignorance and craving, a process which occurs because of a person’s accumulated habitual tendencies.

To be influenced by ignorance and craving in one’s thinking is to see things as one wants them to be or not to be. One’s thinking is bound by personal attachments and aversions. This results in an incorrect discernment of things, in prejudices based on preferences and aversions, in misunderstanding, and in distorted conceptions. Moreover, it is a cause for confusion, listlessness, loneliness, despondency, fear, gratification and subsequent disappointment, stress, and frustration, all of which are various forms of mental affliction.

Reflecting wisely entails seeing things according to the truth or according to causal relationships, not according to ignorance and craving. In other words, one sees things according to their own nature, not according to one’s wishes and desires.

When unawakened persons experience something, their thoughts immediately align themselves with likes and dislikes. The function of wise reflection is to cut off this process and to seize the active role. It then directs the course of thinking in a pure, systematic direction, by contemplating according to causes and conditions. The result is that one understands the truth and generates wholesome states, or at the very least one responds to things in the most appropriate way.

Wise reflection allows people to make good use of thinking, to be a master of their own thoughts, to call upon thinking in order to solve problems and to live at ease. This is the opposite to unwise reflection, which allows thoughts to manipulate and enslave the mind, to drag people into difficulty, oppress them in various ways, and take away their independence. Note also that in the course of wise reflection, mindfulness and clear comprehension are constant factors inherent in the process, because wise reflection constantly nourishes these factors.

In sum, wise reflection cuts off ignorance and craving. These two negative qualities always appear in tandem, although in some cases ignorance is prominent and craving unpronounced, while at other times craving is dominant and ignorance concealed.16 Given this fact, it is possible to present two definitions for wise reflection, according to the dominant role of either ignorance or craving: wise reflection is a form of thinking that cuts off ignorance; or it is a form of thinking that cuts off craving. The distinction is as follows:

-

When ignorance is dominant, thinking gets stuck on and revolves around a single theme in a confused and disconnected way. One does not know which direction to go, or else one’s thoughts are incoherent, disordered, and irrational, for example in the case of someone who is caught in fear.

-

When craving is dominant, thinking inclines in the direction of likes and dislikes, preferences and aversions, or attachment and revulsion. One is preoccupied with those things one likes or dislikes, and one’s thinking is shaped in accord with pleasure and displeasure.

This distinction notwithstanding, on a profound level ignorance is the source of craving, and craving reinforces ignorance. Therefore, if one is to eliminate all affliction and unwholesomeness completely, one must go to the source and eliminate ignorance. {627}

Ways of Reflecting Wisely

The ways of reflecting wisely here refers to the practical application of yoniso-manasikāra. Although there are many methods for applying wise reflection, technically speaking they are divided into two main categories:

-

Wise reflection aiming directly at the cutting off or elimination of ignorance.

-

Wise reflection aiming at cutting off or reducing craving.

Generally speaking, the first method is necessary for the final stages of Dhamma practice, because it gives rise to an understanding according to the truth, which is a requirement for awakening. The latter method is most often used during preliminary stages of practice, with the purpose of building a foundation for virtue or of cultivating virtue, in order to be prepared for more advanced stages. This method is limited to subduing mental defilement. Many methods of applying wise reflection, however, can be used for both benefits simultaneously: for eliminating ignorance and for reducing craving.

The chief methods for applying wise reflection contained in the Pali Canon can be classified as follows:

-

The method of investigating causes and conditions.

-

The method of analyzing component factors.

-

The method of reflecting in accord with the three universal characteristics (sāmañña-lakkhaṇa).

-

The method of reflecting in accord with the Four Noble Truths (reflection used to solve problems).

-

The method of reflecting on the relationship between the goals (attha) and the principles (dhamma) of things.

-

The method of reflecting on the advantages and disadvantages of things, and on the escape from them.

-

The method of reflecting on the true and counterfeit value of things.

-

The method of reflection in order to rouse wholesome qualities.

-

The method of reflection by dwelling in the present moment.

-

The method of reflection corresponding to analytic discussion (vibhajja-vāda). {628}

Investigation of Causes and Conditions

The method of investigating causes and conditions refers to a contemplation of phenomena in order to ascertain the truth, or to a contemplation of dilemmas in order to find a solution by examining various interrelated causal factors. It can also be described as the way of thinking in line with ’specific conditionality’ (idappaccayatā) or according to the teaching on Dependent Origination (paṭiccasamuppāda). This is a fundamental form of wise reflection, and it is sometimes referred to when describing the Buddha’s awakening.

This form of reflection is not restricted to beginning at the results and then investigating the causes and conditions. In the way of thinking in line with specific conditionality it is also possible to begin with a cause and then trace its results, or to select any point in the middle of a process and then track either forwards to the end result or backwards to the source.

In the Pali Canon this form of wise reflection is described as follows:

- 1. Reflections on mutual conditionality: here, a noble disciple reflects wisely on how all conditioned things are interdependent, enabling them to exist:

Monks, it would be better for the uninstructed worldling to take this body composed of the four great elements as a ’self’; but for him to take the mind as a ’self’ is truly unsuitable. For what reason? Because this body composed of the four great elements is seen standing for one year, for two years, for three, four, five, or ten years, for twenty, thirty, forty, or fifty years, for a hundred years, or even longer. But that which is called ’mind’ or ’mentality’ or ’consciousness’ arises as one thing and ceases as another by day and by night.

Monks, in regard to that collection of great elements, the instructed noble disciple attends closely and carefully to dependent origination thus: ’When this exists, that comes to be; with the arising of this, that arises. When this does not exist, that does not come to be; with the cessation of this, that ceases.’ In dependence on contact acting as a basis for pleasant feeling, a pleasant feeling arises. With the cessation of that contact acting as a basis for pleasant feeling, that pleasant feeling arising dependent on that contact … ceases and subsides. In dependence on contact acting as a basis for painful feeling, a painful feeling arises. With the cessation of that contact acting as a basis for painful feeling, that painful feeling … ceases and subsides. In dependence on contact acting as a basis for neutral feeling, a neutral feeling arises. With the cessation of that contact acting as a basis for neutral feeling, that neutral feeling … ceases and subsides.

Monks, just as heat is generated and fire is produced from the friction of two fire-sticks, but with the separation and laying aside of the sticks the resultant heat ceases and subsides; so too in dependence on contact acting as a basis for pleasant feeling, a pleasant feeling arises, and with the cessation of that contact acting as a basis for pleasant feeling, that pleasant feeling arising dependent on that contact … ceases and subsides….17 {629}

S. II. 96-7.

- 2. Inquisitive reflection or the posing of questions; e.g. the following contemplation by the Buddha:

Then it occurred to me: ’When what exists does clinging come to be? By what is clinging conditioned?’ Then, through careful attention, I knew by way of wisdom: ’When there is craving, clinging comes to be; clinging has craving as its condition.’

Then it occurred to me: ’When what exists does craving come to be? By what is craving conditioned?’ Then, through careful attention, I knew by way of wisdom: ’When there is feeling, craving comes to be; craving has feeling as its condition….’18

S. II. 10, 104.

For more on this form of wise reflection see Chapter 4 on Dependent Origination.

Analysis of Component Factors

The analysis of component factors, or the elaboration on a specific subject matter, is another form of reflection which aims to generate an understanding of things as they truly are.

This form of contemplation is most often used to recognize the true insubstantiality or selflessness of all things, in order to give up clinging to conventions and designations (sammati-paññatti). In particular, this refers to a contemplation of beings or people as existing merely as a collection of assorted aggregates (khandha), each of which exists dependent on subsidiary conditional factors. This form of reflection is conducive to seeing the ’selfless’ nature of things (anattā).

A clear discernment of the selfless nature of things, however, normally requires the simultaneous participation by the previous kind of reflection (investigative reflection) and/or the following kind of reflection (reflection in accord with the three characteristics; see below). Through careful analysis one sees how the five aggregates are interdependent and subject to related causes and conditions; they are not truly independent. Moreover, these aggregates and conditional factors all proceed according to natural laws, that is, they exist in a perpetual state of rise and decay; they are unstable, unenduring, and impermanent.

If one is unable to accurately see this rising and ceasing of phenomena – their conditionality and their oppression by various factors – by way of investigative reflection described above, which can be a difficult task, one can reflect on these attributes as universal characteristics of all things, which is encompassed in the third kind of contemplation below. In the Pali Canon this second kind of wise reflection is mentioned together with the third kind.

The commentaries, however, which are aligned with later Abhidhamma texts, prefer to distinguish this second kind of reflection, and they classify it is a mode of detailed analysis (vibhajja-vidhi).19 Furthermore, they tend to begin with a basic analysis by focusing on mentality and corporeality (nāma-rūpa), rather than immediately analyzing the five aggregates.

This kind of reflection is not restricted to analyzing and distinguishing various factors, but also includes classification and categorization. The emphasis, however, is given on analysis and it is thus referred to as vibhajja (’detailed analysis’). {630}

In the traditional practice of insight meditation as described in the commentaries, the basic analysis of mentality and corporeality is referred to as ’analysis of mind and body’ (nāmarūpa-vavatthāna) or ’contemplation of mind and body’ (nāmarūpa-pariggaha).20 Here, one does not look at people according to their conventional names and designations, of being ’them’ or ’us’, ’Mr. A’ or ’Mrs. B’. Instead one sees them as a combination of physical and mental phenomena. One determines each of the component factors in such a way: ’This is material form, this is mind’, ’material form has these specific characteristics, mental phenomena have these specific characteristics’, ’this factor has this kind of attribute and is thus classified as “form”, while this factor has another kind of attribute and is thus classified as “mind”.’

An analysis of human beings reveals only mind-and-body, or material and mental phenomena. Having trained in such discernment, or gaining skill at such reflection, when encountering living beings and other objects, one will see them as simply a collection of mental and physical elements. They are merely natural phenomena, which are empty of any kind of true substance or permanent self. One’s course of thinking helps to prevent one from being misguided or from overly attaching to conventional reality.

Examples in the Pali Canon of this kind reflection are as follows:

Just as, with an assemblage of parts,

The word ’wagon’ is used,

So, when the aggregates exist,

There is the convention ’a being’.S. I. 135.

Friends, just as when a space is enclosed by timber, twine, clay and thatch, it comes to be called a ’house’, so too, when a space is enclosed by bones and sinews, flesh and skin, it comes to be called a ’body’ (rūpa).

M. I. 190.

Monks, suppose that this river Ganges was carrying along a great lump of foam. A man with good sight would inspect it, examine it, and carefully investigate it.21 By inspecting it, examining it, and carefully investigating it, it would appear to him to be void, empty and insubstantial. For what substance could there be in a lump of foam?

So too, monks, whatever kind of material form there is, whether past, future, or present … far or near: a bhikkhu inspects it, examines it, and carefully investigates it. By inspecting it, examining it, and carefully investigating it, it would appear to him to be void, empty, insubstantial. For what substance could there be in material form?22

Form is like a lump of foam,

Feeling like a water bubble;

Perception is like a mirage,

Volitions like a plantain trunk,

And consciousness like an illusion,

So explained the Kinsman of the Sun.

However one may consider,

And carefully investigate [these five aggregates],

They are but void and empty. {631}S. III. 140-3.

Reflection in Line with Universal Characteristics

Reflection in line with universal characteristics, or reflective discernment of natural truths, refers to a clear understanding of things as they are: an understanding of how things exist, and must exist, according to their own nature. The focus of this reflection is on living beings and things that ordinary people are aware of, that is, conditioned things – things arising from and shaped by causes and conditions and subject to conditionality.

One of these natural truths is the law of impermanence, that all conditioned things, once they are arisen, must cease; they are inconstant, unstable, unenduring, and impermanent (anicca).

Likewise, all conditional factors, both internal and external, perpetually arise and cease. Their interaction with one another causes conflict and friction, which results in conditioned things being under stress. They are unable to maintain an original state of existence and they are subject to alteration and disintegration, a truth which is referred to as dukkha.

The very nature of conditioned phenomena means that they do not belong to anyone, they are not subject to anyone’s wishes or desires, and they cannot be truly owned or controlled by anyone. Similarly, they possess no ’soul’ or ’essence’, either internal or external, which is able to dictate or rule over them. They exist according to their own nature; they exist according to causes and conditions, not according to anyone’s will. This is referred to as the truth of ’nonself’ (anattā).

The reflection here entails an acknowledgement of how all things one engages with exist equally as natural phenomena; they are conditioned formations, existing dependent on conditional factors.

The reflection in line with universal characteristics can be divided into two stages:

-

The first stage includes a discernment and acknowledgement of the truth. At this stage one relates to things in harmony with nature. Such conduct is marked by wisdom and an inner freedom; one is not bound by things.

Even if one encounters unpleasant or undesirable circumstances, one is able to reflect on how these things, or these situations, proceed in line with a natural course and exist according to causes and conditions. By thinking in this way one begins to accept one’s situation; one is consequently released from suffering, or at the very least one’s suffering abates.

When one possesses greater mental agility, all one needs to do in such challenging situations is to establish mindfulness and call to mind: ’I will see things according to the truth, not how I want them to be.’ By doing this one’s suffering will decrease immediately, because one begins to be released – one does not subject oneself to stress. Indeed, one does not create a sense of self that is subject to stress.

-

The second stage includes managing and resolving things in line with causal factors. Here one acts with insight, wisdom, and freedom.

When one acknowledges the conditional nature of things and one wishes for things to be a particular way, one studies and understands the causes and conditions required for things to reach a desired result. One then acts and deals with things at their specific conditional factors. When one fulfils the necessary conditions, irrespective of whether one desires the result or not, it will occur automatically. Similarly, if these necessary conditions are lacking, the result will fail, regardless of one’s desires. In sum, one deals with things by way of knowledge and in line with conditional factors, not through willpower or desire. {632}

In terms of Dhamma practice, all one needs to do is acknowledge one’s wishes, determine the relevant causes and conditions, and then deal with matters at the point of these conditional factors. By practising in this way one extricates oneself from problems; one is not bound. One does not allow one’s desires to lead one into oppression (one does not allow one’s desires to create a fixed sense of identity). One both acts directly in line with causes and conditions, and allows things to proceed according to such causes and conditions. This way of practice is both the most effectual and is also free from suffering.

This second stage of reflection in line with universal characteristics is related to the fourth kind of reflection described below, that is, the fourth kind of reflection takes over from the third.

In the traditional practice of insight development (vipassanā), which was developed into a formal system described in the commentaries, the teaching on the seven forms of purity (visuddhi) is used as the master template.23 In this context, the commentaries use the list of different forms of knowledge (ñāṇa) described in the Paṭisambhidāmagga as a set of criteria,24 and maintain the basic contemplation of phenomena, of separating them into ’mind-and-body’ (nāma-rūpa).