Introduction to the Middle Way

Introduction

The Middle Way (majjhimā-paṭipadā), also known as the Path (magga, i.e. the fourth Noble Truth), embodies a set of principles for Buddhist practice: it is a complete code of Buddhist conduct. It comprises the practical teachings, based on an understanding of Buddhist theoretical teachings, which guide people to the goal of Buddhism according to natural processes. It is a way of actualizing the teachings in one’s own life, a method of applying natural laws and benefitting from them to the highest degree. To gain an initial understanding of the Middle Way, let us consider this teaching by the Buddha from the first sermon, the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta:

The Path as the Middle Way

Monks, these two extremes should not be followed by one who has gone forth into homelessness. What two? The indulgence in sensual happiness in sense pleasures, which is inferior, vulgar, low, ignoble, and hollow; and the pursuit of self-mortification, which is painful, ignoble, unbeneficial. The Tathāgata has awakened to the Middle Way, which does not get caught up in either of these extremes, which gives rise to vision, which gives rise to knowledge, which leads to peace, to direct knowledge, to enlightenment, to Nibbāna.

And what is that Middle Way (majjhimā-paṭipadā)…? It is this Noble Eightfold Path; that is, right view, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration.

V. I. 10; S. V. 421.

This teaching provides a complete summary of the meaning, essence, and purpose of the Middle Way. Note that it is a ’middle’ way, or ’middle’ path, because it does not get caught up in either of the two extremes (note, however, that this should not be understood to mean that the path lies between these two extremes):

-

Kāma-sukhallikānuyoga: indulgence in sensual pleasures; the extreme of sensual indulgence; extreme hedonism.

-

Atta-kilamathānuyoga: the extreme of self-mortification; extreme asceticism.

Occasionally, Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike give the expression the ’middle way’ a very broad meaning, to denote an action or thought that lies between two opposing actions or thoughts, or between actions and thoughts performed and held by two separate people or parties.

This kind of midpoint or middle way does not have any solid basis; one must wait until two opposing parties arise in order to determine the halfway point, which hinges on the degree of belief or practice of these two factions. The midway shifts according to the changing stances of the two sides. Sometimes this kind of middle way appears to be the same as the Middle Way in Buddhism (majjhimā-paṭipadā), but in fact it is counterfeit. {526}

The true Middle Way has definite criteria. The validity of the Middle Way rests with it having a clearly defined objective or goal. With the goal clearly defined, the path leading to this goal, or conduct that is apt, correct, and fruitful, is the Middle Way.

This is similar to shooting an arrow or a gun – it is necessary to have a clear target. Accurate or correct shooting is any action expedient to having the arrow or bullet reach the target. The ’middle way’ in this context is shooting precisely and directly at the target.

All deviating shots, veering off to any number of directions, are flawed and inaccurate. In contrast to these errant shots, one sees that there is only one target, which is directly in the middle and clearly defined, and the path leading to the target likewise is a middle path.

The correct path has its own true goal, which is not determined by trajectories of the errant shots. The Middle Way has the definite goal of liberation – the end of suffering.

The Path (magga) – the system of thought, action, and conduct that is consistent with and effective in regard to this goal – is thus the ’Middle Way’ (majjhimā-paṭipadā).

Because the Middle Way has a clearly defined goal, or because the Middle Way is dependent on having such a goal, a Dhamma practitioner must know this goal in order to walk on the Path – one must know in which direction one is going. For this reason the Middle Way is a path of wisdom and begins with right view: it begins with an understanding of one’s problems and of one’s destination. It is a path of understanding, reason, and acceptance, and requires courage to face the truth.

When people possess this knowledge and courage, they are able to manage their lives on their own, to live a correct and virtuous life independently, without relying on external sacred, supernatural, or divine powers. And when people have developed confidence based on their own wisdom, they need not get caught up in and worried about things they believe to exist outside of the normal human sphere. This confidence is one attribute of the Middle Way.

When one understands one’s problems and the way to the goal, a traveller on the Path gains the additional understanding that the Middle Way gives value to one’s life. There is more to life than succumbing to worldly currents, being enslaved by material enticements, or wishing solely for delicious sensual pleasures, by allowing one’s happiness, virtue, and value to be utterly dependent on material things and the fluctuations of external factors. Instead, one cultivates freedom and self-assurance, and one recognizes one’s own inherent value.

Besides not inclining towards the extreme of materialism, to the point of enslavement and dependency on material things, the Middle Way also does not incline towards spiritual extremes. It does not teach that all things are exclusively dependent on effort and mental attainments, to the point that one abandons material things and neglects one’s body, resulting in a form of self-mortification. {527}

Conduct in accord with the Middle Way is characterized by non-oppression, both towards others and oneself, and by an understanding of phenomena, both material and mental. One then practises with accurate knowledge, in tune with causes and conditions, and conducive to bearing fruit in accord with the goal. One does not practise simply to experience pleasurable sense impressions or out of some naive belief that things must be done in a particular way.1

If someone alludes to a middle way or to walking a middle path, one should ask whether he or she understands the problems at hand and the goal to which this path leads.

The principles of the Middle Way can be applied to all human work and activity. Generally speaking, all human systems, traditions, academic fields of study, institutions, and everyday activities, like formal education, aim to solve problems, reduce suffering, and help people realize higher forms of virtue. A proper relationship to these systems, traditions, etc. requires an understanding of their objective, which is to relate to them with wisdom and right view, in accord with the Middle Way.

It is commonly apparent, however, that people often practise incorrectly and do not understand the true objectives of these systems, procedures, and activities.

Incorrect practice deviates in one of two ways: some people use these systems and activities as an instrument or opportunity for self-gratification, for instance in politics they use this system as a way to seek material gain, fame, and power. They perform their function and increase their formal knowledge in order to enrich themselves and to achieve influential positions, to maximize their own comfort and pleasure. They do not act in order to achieve the true objective of that work or field of knowledge. Rather than having right view, they are subject to wrong view (micchā-diṭṭhi).

Another group of people are resolutely dedicated to work or study. They raise money, muster inner strength, and sacrifice time with great devotion, but they do not understand the true purpose of the activity – they do not know, for example, what problems should be solved by performing it. They end up wasting their time, money, and energy, causing themselves trouble and fatigue in vain. This is another way of lacking right view. {528}

The first group of people set their own objectives in order to gratify craving. They do not act in accord with the true objective of the activity or work. The second group of people simply act without understanding the real purpose of their actions. These two groups fall into two extremes. They do not walk the Middle Way and they generate more problems for themselves.

Only when they are able to follow the Middle Way, acting with knowledge conforming to the true objective of that particular activity, are they able to successfully solve problems and eliminate suffering.

In sum, if one does not begin with right view, one does not access the Middle Way; if one does not follow the Middle Way, one is not able to reach the end of suffering. (See Note The Middle Way)

The Path as a Practice and Way of Life for both Monks and Laypeople

Occasionally, people may use the expression ’middle way’ to denote effort that is neither overly rigid nor overly slack, or work or training that is performed neither with laziness nor by forceful straining. Although in these contexts the expression ’middle way’ may share some attributes with the Middle Way, it is not absolutely correct. Even those people who follow the Middle Way may apply an overly forceful amount of effort, or not enough effort, and thus not realize the fruit of practice. In these circumstances, the Buddha used the expression viriya-samatā to refer to correct effort (this term means correct, balanced, or consistent effort; samatā = samabhāva = evenness, balance, suitability, moderation, consistency); see: Vin. I. 181; A. III. 374-5.

Sometimes, when people are sure of walking the correct path, fully confident and prepared, they are encouraged to muster all of their strength and energy, even if they must surrender their life in the process. For example, the Buddha himself was fearlessly determined on the night of his awakening (A. I. 50). One should not confuse this subject with the Middle Way.

Monks, I do not praise the wrong path, whether for a layperson or for one gone forth. Whether it is a layperson or one gone forth who is practising wrongly, because of undertaking the wrong way of practice he does not attain the right path which is wholesome. And what is the wrong path? It is: wrong view … wrong concentration.

I praise the right path, both for a layperson and for one gone forth. Whether it is a layperson or one gone forth who is practising correctly, because of undertaking the right way of practice he attains the right path which is wholesome. And what is the right path? It is: right view … right concentration.2

S. V. 18-19.

Monks, just as the river Ganges flows, slopes and inclines towards the ocean, so too a monk who develops and cultivates the Noble Eightfold Path aspires, slopes and inclines towards Nibbāna.

S. V. 41.

Master Gotama, just as the river Ganges flows, slopes, inclines towards, and merges with the ocean, so too Master Gotama’s assembly with its homeless ones and its householders aspires, slopes, inclines towards, and merges with Nibbāna.

M. I. 493-4.

These passages on right and wrong practice reveal how the Buddha intended the Middle Way to be applicable to all people, both renunciants and laity; it is a teaching to be realized and brought to completion by everyone – monks and householders alike. {529}

The Path as a Spiritual Practice Connected to Society

Ānanda, having good friends, having good companions, and a delight in associating with virtuous people is equivalent to the entire holy life. When a monk has a good friend3 … it is to be expected that he will develop and cultivate the Noble Eightfold Path.

S. V. 2-3.

Monks, just as the dawn is the forerunner and precursor of the rising of the sun, so too, having a virtuous friend is the forerunner and precursor for the arising of the Noble Eightfold Path for a monk.

S. V. 29-30.

These passages show the importance of the relationship between people and their social environment, which is a vital factor influencing and supporting Buddhist practice. They show that in Buddhism one’s way of life and spiritual practice is intimately connected to society.

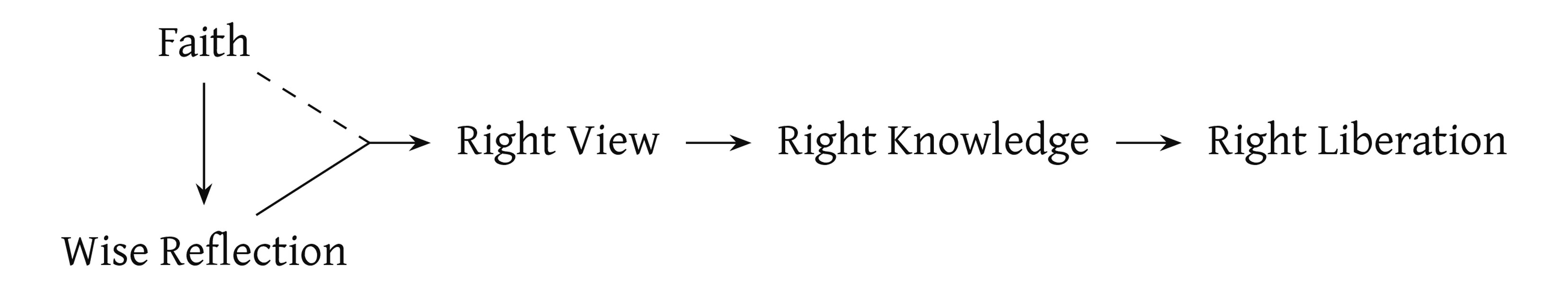

Monks, just as the dawn is the forerunner and precursor of the rising of the sun, so too, the fulfilment of wise reflection (yoniso-manasikāra) is the forerunner and precursor for the arising of the Noble Eightfold Path for a monk. It is to be expected of a monk who has brought wise reflection to completion that he will develop and cultivate the Noble Eightfold Path.

S. V. 31.

This passage introduces the notion that, although social factors are vital, one should not overlook the importance of spiritual factors inherent in an individual. Both internal and external factors can be the impetus for spiritual practice and conducting one’s life correctly. In fact, these two factors are mutually supportive.

This passage emphasizes that correct spiritual practice, or a virtuous life, results from the integration of these two factors. And progress on the Path towards the highest goal of life is most successful when these two factors serve and aid one another.

Note, however, that the teachings often give more emphasis to the social factor of having virtuous companionship than to the internal factor of wise reflection. There are passages, as the one above, which equate the value of having good friends as equivalent to the entire practice of the Buddhist teachings, referred to here as the ’holy life’ (brahmacariya). This is because most people must rely on social factors in order to initiate right practice and a virtuous life, or to begin on the noble path.

Moreover, wholesome social factors act as both the trigger for enabling wise reflection and for the support for augmenting and advancing wise reflection. {530}

There are very few exceptions to this rule, namely, those extraordinary persons who can progress safely on the Path relying solely on their own inherent spiritual endowment. They are able to commence with wise reflection without outside influence and to constantly summon wise reflection without relying on social factors.4 These passages are thus intended for the majority of people, who possess an average degree of spiritual faculties.

This subject of social factors in relation to internal factors is very important and will be addressed at more length in subsequent chapters.

The Path as a Way to End Kamma

This Noble Eightfold Path is the way leading to the cessation of kamma, that is, right view … right concentration.

A. III. 414-5; S. IV. 133.

The Middle Way here is the way leading to the cessation of kamma. It is very important, however, not to interpret this to mean the following: that it simply refers to the passing away of the body, to dying;5 or that it refers to ending kamma by not producing kamma or not doing anything at all, which is the doctrine of the Jains, as described in the chapter on kamma; or that it refers to abandoning activity and living in a state of passivity.

The ending of kamma requires activity and earnest endeavour, but it is action in accord with the Middle Way, in accord with a proper method of action, as opposed to errant behaviour.

And the expression ’cessation of kamma’ does not mean inactivity and complacency, but rather an end to the actions of unawakened persons and the start to actions of noble beings.

Ordinary people act with craving and grasping; they attach to personal ideas of what is good and bad and to things providing some form of personal advantage. The actions of such people are technically referred to as ’kamma’, which is classified as either good or bad.

The end of kamma refers to ceasing to act with an attachment to personal views of right and wrong and with a hunger for personal gain. When personal attachments to right and wrong are absent, the subsequent actions are not referred to as ’kamma’, because kamma requires taking sides, requires for things to be either good or evil.

The actions of awakened beings, on the other hand, are in harmony with the pure reason and objective of that particular activity; they are not tied up with any craving or grasping.

Awakened persons do no wrong, because no more causes or conditions exist which would compel them to misbehave; no greed, hatred, or delusion remains in their minds which would drive them to seek personal gain. They only perform good actions, acting solely with wisdom and compassion. The term ’good’ here, however, is used according to the understanding of general people. Awakened beings do not attach to the ideas of personal goodness, or to goodness as some mark of personal identity.

Generally speaking, when ordinary people perform good deeds, they do not act purely in accord with the true objective of such deeds, but tend to expect some kind of personal reward as a result. On a subtle level this may be a wish for personal prestige, or even a sense of internal wellbeing that ’I’ have done good. {531}

Awakened persons, however, perform good acts purely in accord with the purpose, objective, and necessity of such an action. Their actions are thus technically not referred to as ’kamma’.

The Path is a way of practice for bringing an end to volitionally produced actions (kamma); when kamma ceases only pure actions (referred to as ’doing’ – kiriyā), following the guidance of wisdom, remain.

This is the distinction between the mundane and the transcendent courses of action. The Buddha and the arahants teach and act for the welfare of all people without their actions constituting kamma. In the vernacular, their actions are referred to simply as ’acts of goodness’.

The Path as a Practical Tool

Monks, suppose a man in the course of a long journey saw a great expanse of water, whose near shore was frightening and dangerous and whose far shore was safe and free from danger, but there was no ferryboat or bridge crossing to the other shore. Then he thought: ’There is this great expanse of water, whose near shore is frightening and dangerous…. Suppose I collect grass, pieces of wood, branches, and leaves and bind them together into a raft, and supported by the raft and making an effort with my hands and feet, I got safely across to the far shore.’

And then the man collected grass … and leaves and bound them together into a raft … and got safely across to the far shore. Then, when he had got across and had arrived at the far shore, he might think thus: ’This raft has been very helpful to me, since supported by it … I got safely across to the far shore. Suppose I were to hoist it on my head or load it on my shoulders, and then go wherever I want.’ Now, monks, what do you think? By doing so, would that man be doing what should be done with that raft?’

[The monks replied, ’No, venerable sir’, and the Buddha continued:]

By doing what would that man be doing what should be done with that raft? Here, monks, when that man got across and had arrived at the far shore, he might think thus: ’This raft has been very helpful to me…. Suppose I were to haul it onto the dry land or tie it up at the water’s edge, and then go wherever I want.’ Now, monks, it is by so doing that that man would be doing what should be done with that raft.

The Dhamma is similar to a raft, which I have revealed to you for the purpose of crossing over, not for the purpose of grasping. When you thoroughly understand the Dhamma, which is similar to a raft as I have illustrated, you should abandon even good states, not to mention bad states.

M. I. 134-5.

Monks, purified and bright as this view is, if you adhere to it, are enthralled by it, cherish it, and treat it as a possession, would you then understand the Dhamma that has been taught as similar to a raft, being for the purpose of crossing over, not for the purpose of grasping?6

M. I. 260-61.

These two passages caution against grasping at virtuous qualities (including grasping at the truth or at what is right), by which a person fails to benefit from their true value and objective. Moreover, they emphasize viewing all virtuous qualities and all Dhamma teachings as means or methods leading to a specific goal; they are neither arbitrary nor are they ends in themselves. {532}

When practising a particular Dhamma teaching, it is important to realize its objective, along with its relationship to other teachings. The term ’objective’ here does not only refer to the final goal, but also to the vital function of that particular teaching or spiritual quality: to know, for example, how cultivating a specific quality supports or generates other qualities, what its limits are, and once its function is complete, to know what other qualities take over responsibility.

This is similar to being on a journey, in which one must use different vehicles at various stages to pass over land, water, and air. It is insufficient to simply have a general idea of one’s destination. One needs to know how far each vehicle can travel, and having reached a location one knows which is the next vehicle to use.7

Spiritual practice lacking insight into these objectives, requirements, and interrelationships is limited and obstructed. Even worse it leads people off the right track, it misses the target, and it is stagnant, futile and fruitless. Aimless spiritual practice causes misunderstandings and harmful consequences. It undermines such important spiritual qualities as contentment and equanimity.

The Path as the Holy Life

Bhikkhus, you should wander forth for the welfare and happiness of the manyfolk, for the compassionate assistance of the world, and for the wellbeing, support and happiness of gods and human beings…. You should proclaim the Dhamma … you should make known the holy life.

Vin. I. 20-21.

’The holy life, the holy life. What now, friend, is the holy life, and who is a follower of the holy life, and what is the final goal of the holy life?’

’This Noble Eightfold Path is the holy life; that is, right view … right concentration. One who possesses this Noble Eightfold Path is called a liver of the holy life. The end of lust, the end of hatred, the end of delusion; this is the final goal of the holy life.’

S. V. 7-8, 16-17, 26-7.

What is the fruit of the holy life? The fruit of stream-entry, the fruit of once-returning, the fruit of non-returning, the fruit of arahantship; this is the fruit of the holy life.

S. V. 26.

So this holy life, monks, does not have gain, honour, and renown as its blessing, or the perfection of virtue as its blessing, or the attainment of concentration as its blessing, or knowledge and vision as its blessing. But it is this unshakeable deliverance of mind that is the goal of this holy life, its heartwood, and its end.8 {533}

M. I. 197; 204-205.

The term brahmacariya is generally understood in a very narrow sense, as living a renunciant life and the abstention from sexual intercourse, which is only one meaning of this term. (See Note Definitions of Brahmacariya)

The commentaries give twelve definitions for the term brahmacariya. The common definitions include: the entire Buddhist religion; practice according to the Eightfold Path; the four divine abidings (brahmavihāra); generosity (dāna); contentment with one’s own wife; celibacy; and exposition of the Dhamma (dhamma-desanā): MA. II. 204. DA. I. 177 provides ten definitions; ItA. I. 109 provides five definitions; KhA. 152 and SnA. I. 299 provide four definitions. The Cūḷaniddesa defines brahmacariya as the abstention from sexual intercourse (’unwholesome practice’ – asaddhamma) and adds: Apica nippariyāyena brahmacariyaṁ vuccati ariyo aṭṭhaṅgiko maggo – ’moreover, generally speaking, the Eightfold Path is called the holy life’ (Nd. II. 10, 48).

The Mahāniddesa defines cara as: vihara (’abide’, ’exist’); iriya (’movement’); vatta (’go’, ’revolve’); pāla (’protect’); yapa (’proceed’); yāpa (’nourish’, ’sustain life’). See, e.g.: Nd. I. 51, 159, 314.

Here are the substantiated meanings of these words (rūpa-siddhi): cariya (nt.) and cariyā (f.) stem from cara (root – dhātu) + ṇya (affix – paccaya) + i (added syllable – āgama). Cariya here is the same word used in the Thai compounds cariya-sikkhā (จริยศึกษา – moral education) and cariya-dhamma (จริยธรรม – virtuous conduct).

In fact, the Buddha used this term to refer to the entire system of living life according to Buddhist principles or to Buddhism itself. This is evident from the passages in which the Buddha sends forth his disciples in order to ’proclaim the holy life’, and also in the passage in which he states that the holy life will truly flourish when members of the four assemblies – the bhikkhus, bhikkhunis, laymen, and laywomen – both renunciants (brahmacārī) and householders (kāmabhogī – ’those who enjoy sense pleasures’; those who have families) – understand and practise the Dhamma well.9

Brahmacariya is made up of the terms brahma and cariya. Brahma means ’excellent’, ’superior’, ’supreme’, ’pure’.10 Cariya is derived from the root cara, which in a concrete sense means ’to travel’, ’to proceed’, ’to wander’, and in an abstract sense it means ’behaviour’, ’to lead one’s life’, ’to conduct one’s life’, ’to exist’. Here, we are interested in the figurative or abstract sense. (Note that occasionally brahmacariya is written as brahmacariyā.) (See Note Definitions of Brahmacariya for further analysis.)

As a compound word brahmacariya thus means: excellent conduct; excellent behaviour; pure, divine conduct (conduct resembling that of the Brahma gods); leading one’s life in an excellent way; living in an excellent way; or an excellent life.11

The term cariya-dhamma (จริยธรรม) is a newly established word in the Thai language. Although in Pali the word cariya occurs on its own, there is no contradiction to add the word dhamma. Cariya-dhamma here means ’upright conduct’, ’virtuous conduct’, or ’basis of conduct’. It refers to principles of behaviour or principles of conducting one’s life. Here, I will not discuss the wider academic notions of the term cariya-dhamma, but focus simply on its Buddhist connotations. {534}

Adopting this new term, one can define brahmacariya as excellent virtuous conduct – excellent cariya-dhamma. This excellent conduct, or ’supreme’ (brahma) conduct, refers specifically to the system of conduct revealed and proclaimed by the Buddha.

According to the Buddha’s words quoted above, the holy life – excellent conduct or Buddhist conduct – is equivalent to the Path (magga) or to the Middle Way (majjhimā-paṭipadā). Likewise, one who practises the holy life (brahmacārī) – one whose conduct conforms to Buddhist principles – lives according to the Path or practises in line with the Middle Way.

The Buddhist teachings state that the Path – the Middle Way – is a system of conduct, a system of practical application, a guideline for living a virtuous life, or a way for people to lead their lives correctly, which leads to the goal of freedom from suffering.

The following points provide a summary of brahmacariya: the holy life, excellent conduct, or conduct conforming to the middle way of practice:

Virtuous conduct

Virtuous conduct is connected to truth inherent in nature; it is based on natural laws. It is a matter of applying knowledge about natural, causal processes in order to benefit human beings, by establishing a system of practice or a code of conduct, which is effective and in harmony with these laws.

This harmony with nature can be viewed from two perspectives. First is to focus on the source, that is, to see that virtuous conduct is determined by natural truths. Second is to focus on the goal, to recognize the purpose and objective for such conduct. One practises the holy life in order to benefit oneself and all of humanity, to lead a virtuous life, to foster goodness in society, to lead to the welfare and happiness of all people.

In relation to society, for example, by wishing for people to live together peacefully, one advocates and establishes principles of behaviour, say on how to interact with others or how to act in relation to one’s natural environment. These principles are established according to the truth of human nature, which has certain requirements and attributes dependent on other people and on the environment.

In terms of individuals, by wishing for people to be peaceful, bright, happy, and mentally healthy, one teaches them how to control and direct their thoughts and how to purify their minds. These methods of generating wellbeing are established according to the universal nature of the human mind, which is subject to causal, immaterial laws inherent in nature. Wishing for people to experience the refined happiness of jhāna and the highest levels of insight, one teaches them to train the mind, to reflect, to relate to things properly, and to develop various stages of wisdom. These methods of higher spiritual practice are established according to the laws governing the functioning of the mind and the laws of conditioned phenomena. {535}

The term cariya-dhamma, which is a synonym for brahmacariya, encompasses all of these kinds of spiritual practice, which can be divided into many different levels or stages. Cariya-dhamma can be defined as applying an understanding of reality to establish wholesome ways of living, so that people can realize the highest forms of wellbeing.

Brahmacariya

Brahmacariya – excellent conduct, the Path, or the Middle Way – is equivalent to the entire practical teachings of Buddhism. This term has a much broader definition than the Thai term sīla-dhamma (ศีลธรรม – ’morality’, ’ethical behaviour’).12 In regard to its general characteristics, subject matter, and objective, sīla-dhamma has a narrower meaning. Generally speaking, sīla-dhamma refers to external behaviour by way of body and speech, to non-harming, to abstaining from bad actions, and to mutual assistance in society.

In terms of its content or subject matter, this latter term tends to be limited to moral conduct (sīla): to restraint of body and speech, and to expressions of the divine abidings, for instance lovingkindness and compassion. Although it is connected to the mind, it does not include the development of concentration or the cultivation of wisdom in order to realize the truth of conditioned phenomena.

As to its objective, it emphasizes social wellbeing, peaceful coexistence, worldly progress – say in terms of material gain, reputation, and prestige – and being reborn in a happy realm. In short, it is linked to human and divine prosperity (sampatti), to ’mundane welfare’ (diṭṭhadhammikattha), and to the beginning stages of ’spiritual welfare’ (samparāyikattha).

Here, we see that sīla-dhamma is equivalent to sīla – the term dhamma is added simply for the sake of euphony.

Cariya-dhamma

In Thailand, the term cariya-dhamma still causes confusion for people. Some people understand this term as equivalent to sīla-dhamma – to general morality, while others bestow on it an academic or philosophical connotation. I will not go into these various definitions here.

Suffice it to say that similar to the term sīla-dhamma, which is equivalent to sīla, cariya-dhamma is equivalent to cariya (’conduct’, ’behaviour’) – the suffix dhamma does not alter its meaning.

The term cariya-dhamma encompasses the entirety of Dhamma practice, beginning with basic moral conduct. The following factors are included in the principle of cariya-dhamma: moral conduct, developing good family relationships, social harmony, observing precepts in a monastery as a layperson, keeping the duties of a renunciant (samaṇa-dhamma) in the forest, gladdening the mind, fostering mental health, mental training, meditation, insight practice, etc.

As stated above, the term brahmacariya, which contains the term cariya, refers to the Path or to the Middle Way, but it emphasizes behaviour or the way in which one leads one’s life. In essence, the term brahmacariya refers to a system of conducting one’s life with virtue, or to the entire system of Dhamma practice in Buddhism, and it thus incorporates the term sīla-dhamma as used in the Thai language. It also includes the training of the mind, the instilling of virtue, and the development of knowledge and vision (ñāṇa-dassana), which is an aspect of higher wisdom. {536}

In sum, brahmacariya refers to a means of cultivating virtue by way of body, speech and mind, or from the perspective of the threefold training, it is the complete training in moral conduct (sīla), concentration (samādhi), and wisdom (paññā).

The goal of this excellent conduct is to realize every stage of Buddhist spiritual practice, until one has reached the highest goal of the holy life (brahmacariya-pariyosāna): the end of greed, hatred, and delusion, the realization of true knowledge (vijjā), liberation (vimutti), purity (visuddhi), and peace (santi). In sum, one realizes Nibbāna.

For brevity’s sake, brahmacariya is translated here as the ’holy life’ or as ’living an excellent life’. Excellent conduct is not something that can be formulated simply by the whims of influential people or by the consensus of a group or community, and it is not something that should be followed blindly. Establishing true excellent conduct, and having such conduct bear fruit, is dependent on knowledge of reality.

The Path as a Way of Achieving Life Objectives

Your Majesty, I told the bhikkhu Ānanda: ’Ānanda … having good friends, having good companions, and a delight in associating with virtuous people is equivalent to the entire holy life. When a monk has a good friend it is to be expected that he will develop and cultivate the Noble Eightfold Path….’ Therefore, great king, you should train yourself thus: ’I will be one who has good friends, who has good companions, and who delights in associating with virtuous people….’

When, great king, you have good friends, you should dwell by applying this vital principle: heedfulness in respect to wholesome states. When you are heedful and dwelling diligently, your retinue of harem women … your nobles and royal entourage … your soldiers … and even the townspeople and villagers will think thus: ’The king is heedful and dwells diligently. Come now, let us also be heedful and dwell diligently.’

When, great king, you are heedful and dwelling diligently, you yourself will be guarded and protected, your retinue of harem women will be guarded and protected, your treasury and storehouse will be guarded and protected.

One who desires great, burgeoning riches should take great care;

The wise praise diligence performing meritorious deeds.

The wise are heedful

and thus secure both kinds of good (attha):

The good visible in this very life

And the good of the future.

A wise person, by attaining the good,

Is called a sage.Appamāda Sutta: S. I. 87-9; cf.: A. III. 364.

The term attha (’good’) can also be translated as ’substance’, ’meaning’, ’objective’, ’benefit’, ’target’, or ’goal’. In this context it means the true purpose or goal of life, referring to the goal of the holy life or the goal of Buddhism. {537}

Most people know that the highest goal of Buddhism is Nibbāna, for which there exists the epithet paramattha, meaning ’supreme good’ or ’supreme goal’. It is normal that when teaching Dhamma there is great emphasis on practising in order to reach the highest goal.

Buddhism, however, does not overlook the secondary benefits or goals which people may realize according to their individual level of spiritual maturity, and these benefits are often clearly defined, as is evident in the passage above.

As far as I can ascertain, the older texts divide spiritual good (attha) into two categories, as seen in the passage above:

-

Diṭṭhadhammikattha: initial benefits; present good; good in this lifetime.

-

Samparāyikattha: profound benefits; future good; higher good.

In this case, the supreme good (paramattha) is included in the second factor of higher good (samparāyikattha): it is the apex of this second form of spiritual benefit.13 The authors of later texts, however, wished to give special emphasis to the supreme good and thus distinguished it as a separate factor, resulting in three levels of spiritual benefit or spiritual goals:14

-

Diṭṭhadhammikattha: present good; good in this lifetime; visible benefits. This refers to basic or immediate goals, to obvious, everyday benefits. It pertains to external or ordinary, mundane aims and aspirations, like material gain, wealth, prestige, pleasure, praise, social status, friendship, and a happy married life. It also includes the righteous search for these things, a correct relationship to them, the use of these things in a way that brings happiness to oneself and others, communal harmony, and the fulfilment of one’s social responsibilities which leads to communal wellbeing.

-

Samparāyikattha: future good; inconspicuous benefits; profound benefits, which are not immediately visible. It pertains to a person’s spiritual life or to the true value of human life; it refers to higher goals, which act as a surety when one passes away from this world, or are a guarantee for obtaining superior blessings – superior gains – greater than one normally realizes in the world. These benefits include: spiritual development and the increase of virtuous qualities; an interest in moral conduct, meritorious deeds, the cultivation of goodness, and actions based on faith and relinquishment; a confidence in the power of virtue; tranquillity and mental ease; the experience of refined happiness; and the exceptional attributes of jhāna. (Originally, the supreme benefit of awakening was also included in this term.)

A person who realizes these benefits is released from an attachment to material things. One does not overvalue these things to the point of grasping onto them, succumbing to them, or allowing them to be a cause for doing evil. Instead, one gives value to virtue, acts with a love of truth, cherishes a good quality of life, and delights in spiritual development. Reaching this stage produces results that can be used in conjunction with mundane benefits (diṭṭhadhammikattha), and which support oneself and others. For example, instead of using money for seeking sensual pleasures, one uses it to assist others and to enhance the quality of one’s life. {538}

-

Paramattha: supreme benefit; the true, essential good. This refers to the highest goal, the final destination: realization of the truth; a thorough knowledge of the nature of conditioned phenomena; non-enslavement by the world; a free, joyous, and spacious mind; an absence of oppression by personal attachments and fears; an absence of defilements, which burn and corrupt the mind; a freedom from suffering; a realization of internal happiness, which is completely pure and accompanied by perfect peace, illumination, and joy. In other words, this refers to liberation (vimutti): to Nibbāna.

The Buddha acknowledged the importance of all the aforementioned benefits or goals, recognizing that they are connected to an individual’s level of lifestyle, profession, surroundings, and proficiency, readiness, and maturity of spiritual faculties.

From the passage cited above, however, it is evident that according to Buddhism all people should reach the second stage of benefits or goals. It is good to have attained present, immediate benefits, but this is insufficient – one should not rest here. One should progress and realize at least some aspects of profound, spiritual benefits. A person who has obtained the first two levels of benefits, or has reached the first two goals, is praised as a paṇḍita – a person who lives wisely, whose life is not meaningless and void.

The Buddha gave comprehensive practical teachings on how to reach all of these benefits. On some occasions he gave a teaching on how to obtain four kinds of immediate, visible benefits:

-

Uṭṭhāna-sampadā: perseverance; to know how to apply wisdom to manage one’s affairs.

-

Ārakkha-sampadā: to know how to protect one’s wealth and possessions, so that they are safe and do not come to harm.

-

Kalyāṇamittatā: to associate with virtuous people, who support one’s spiritual practice and development.

-

Samajīvitā: to lead a balanced livelihood; to be happy without needing to live lavishly; to keep one’s income greater than one’s expenditures; to maintain savings; to economize.

Similarly, he gave a teaching on how to obtain four kinds of profound, spiritual benefits:

-

Saddhā-sampadā: to possess faith based on reason and in line with the Buddhist teachings; to be deeply inspired by the Triple Gem; to believe in the law of kamma; to be anchored in something virtuous.

-

Sīla-sampadā: to be endowed with moral conduct; to live virtuously and to make a living honestly; to maintain a moral discipline that is suitable for one’s way of life.

-

Cāga-sampadā: the accomplishment of relinquishment; to be generous and charitable; to be ready to help those in need.

-

Paññā-sampadā: to live wisely; to know how to reflect on things; to apply discriminative knowledge; to fully understand the world; to be able to detach the mind from unwholesome states according to the circumstances.15

In regard to the supreme benefit or goal (paramattha), because it is so difficult to understand and to realize, and also because it is the unique factor distinguishing Buddhism from all previous religious doctrines, it is natural that the Buddha gave it great emphasis. There are teachings by the Buddha on the supreme goal spread throughout the Tipiṭaka, and similarly in this text Buddhadhamma this theme has been touched upon frequently. {539}

As for the first two levels of benefits, they have been adequately taught by Buddhist scholars and teachers throughout the ages. The first level – of mundane, immediate benefits – has been taught to lay Buddhists as is suitable to their particular time period and location. Buddhists have readily adopted any teaching in this context that is effective and does not lead to a deviation from the Middle Way. Lay Buddhists themselves are able to elaborate on and adapt these practices as is appropriate to their circumstances.

In the above sutta passage the Buddha emphasizes the quality of heedfulness (appamāda) as a factor which helps to realize all of the aforementioned benefits. Appamāda can be defined as: an absence of indifference, passivity, or neglect; attentiveness, diligence, and ambition; being well-prepared and vigilant; hastening to do that which should be done, adjust that which should be adjusted, and do that which is good. A heedful person knows that diligence is a fundamental spiritual quality, which leads to both immediate and future benefits.

There is the added stipulation here that heedfulness must be firmly established on an association with virtuous people, on having good friends, and on involving such people in one’s activities. Moreover, the Buddha explains heedfulness here to mean ’diligence in regard to wholesome states’ – to engaging in virtuous activities and ’performing meritorious deeds’ (puñña-kiriyā).

The term puñña-kiriyā provides an interesting link to a related subject. When the Buddha on certain occasions spoke about secondary benefits or goals, he reduced his emphasis in relation to the supreme goal. When the focus of the teaching was lowered to one of the secondary goals, the level of practice that he recommended was also lowered or relaxed.

This is the case not only in specific, isolated circumstances; it is true also when he presented general, wide-ranging systems of practice.

We see this in a teaching the Buddha gave in reference to these three stages of benefits. Here, instead of the practice being formulated according to the gradual teaching of the threefold training – of sīla, samādhi, and paññā – as is usual in those teachings focusing primarily on the supreme goal, the system of practice is restructured as the general teaching referred to as ’meritorious action’ (puñña-kiriyā) or the ’bases of meritorious action’ (puññakiriyā-vatthu).

In this teaching, there are likewise three factors, but with different names.16 They are as follows:

-

Dāna: giving, relinquishment, generosity. The reasons for giving are various: to help others who are poor, destitute, or in need; to show goodwill in order to create trust, establish friendship, and develop communal harmony; and to honour virtue, by praising, encouraging and supporting good people. The things given are also various: personal possessions, material objects, and requisites for sustaining life; technical knowledge, advice, guidance on how to live one’s life, or the gift of Dhamma; the opportunity to participate in wholesome activities; and the gift of forgiveness (abhaya-dāna).

-

Sīla: virtuous conduct and earning one’s living honestly; moral discipline and good manners. {540} The main emphasis here is on not harming others and living together peacefully, by maintaining the five precepts: not killing or injuring other beings; not violating other people’s property or possessions; not violating those who are cherished by others – not offending others by dishonouring them or destroying their families; not harming or undermining others by wrong or offensive speech; and not causing trouble for oneself by taking addictive drugs which impair mindfulness and clear comprehension – spiritual qualities that act as restraints, preventing harm and preserving virtue.

In addition to the five precepts one may undertake a training in abstaining from certain luxuries and pleasing sense objects, in living simply and being less dependent on material things, by keeping the eight or ten precepts at suitable times. Alternatively, one may undertake various forms of public service and assistance (veyyāvacca-kamma).

-

Bhāvanā: cultivation of the mind and of wisdom; to undergo mental training in order to develop virtuous qualities, to strengthen and stabilize the mind, and to generate wisdom which truly discerns conditioned phenomena; to have a correct worldview or perspective on life.

The cultivation referred to here is of both concentration and wisdom, which in the threefold training is distinguished as samādhi-bhāvanā (or citta-bhāvanā) and paññā-bhāvanā. Here, the distinction between these two is not emphasized and they are thus combined as a single factor. This factor encompasses a wide range, including right effort (sammā-vāyāma) – the effort to abandon mental defilements and to nurture wholesome qualities – which is part of the samādhi group in the Eightfold Path, and both right view (sammā-diṭṭhi) and right thought (sammā-saṅkappa) – especially the cultivation of lovingkindness, the source of both personal and social wellbeing – which are part of the wisdom group in the Eightfold Path.

The practices recommended in the scriptures for developing this combination of concentration and wisdom include: seeking wisdom and clearing the mind by listening to the Dhamma (dhamma-savana; this includes reading Dhamma books); reciting or teaching the Dhamma; discussing the Dhamma; revising and correcting one’s beliefs, views, and understanding; developing lovingkindness; and general methods of restricting and subduing mental defilements.

It is evident that when the Buddha altered the focus of his teachings to more basic aspects of life or to secondary spiritual achievements, he adjusted the way one should live one’s life, or the system of Dhamma practice, accordingly.

In this simplified system of practice he emphasizes physical and verbal actions, human interactions, and social relationships, which are easy to observe. The two factors of generosity (dāna) and virtuous conduct (sīla) focus on mental development and refinement through the use of basic, external actions as the means of practice. One applies these two factors in order to eliminate coarse defilements.

Practice on the levels of concentration (or the ’higher mind’ – adhicitta) and of wisdom (or ’higher wisdom’ – adhipaññā), on the other hand, deals directly with internal, spiritual matters and is both subtle and difficult. This system of ’meritorious action’ (puñña-kiriyā) does not emphasize this level of practice and thus combines these two factors; moreover, it points out less refined aspects of concentration and wisdom which can be practised and developed in everyday life.

Later generations of Buddhist teachers have tended to use this teaching on meritorious action as appropriate for laypeople. The system of the threefold training is the standard system and encompasses the entire Buddhist practice. The bhikkhu sangha, which symbolizes a community applying the complete model of practice, should act as the leader in undertaking the system of the threefold training.

Besides dividing benefits or goals (attha) vertically as described above, the Buddha also classified benefits horizontally, in order of a person’s responsibilities, or in order of social interactions. Here too it is a threefold division: {541}

Monks, suppose there is a lake whose water is unmuddied, clear, and pristine. A person with good eyesight standing on the bank could see snails, clams, stones, pebbles, and shoals of fish, swimming or stationary, in that lake. Why is that? Because the water is not cloudy. Just so, a monk whose mind is unclouded understands his own benefit (attattha), the benefit of others (parattha), and the benefit of both (ubhayattha). It is possible for him to realize excellent states surpassing those of ordinary people, that is, knowledge and vision (ñāṇa-dassana), which is capable of leading to awakening. Why is that? Because his mind is unclouded.

A. I. 9.

When a person is impassioned with lust,17 overwhelmed and possessed by lust … when a person harbours hatred, is overwhelmed and possessed by hatred … when a person is bewildered through delusion, overwhelmed and possessed by delusion, then he plans for his own harm, for the harm of others, and for the harm of both; and he experiences in his mind suffering and grief. When lust … hatred … delusion has been abandoned, he neither plans for his own harm, nor for the harm of others, nor for the harm of both.

When a person is impassioned with lust … harbours hatred … is bewildered through delusion, he will behave badly by body, speech and mind. When lust … hatred … delusion has been abandoned, he does not behave badly by body, speech or mind.

When a person is impassioned with lust … harbours hatred … is bewildered through delusion, he does not understand as it really is his own welfare, others’ welfare, or the welfare of both. When lust … hatred … delusion has been abandoned, he understands as it really is his own welfare, others’ welfare, and the welfare of both.

Lust, hatred and delusion cause a person to be blind, visionless, and foolish; they restrict wisdom, cause affliction, and are not conducive for Nibbāna. Seeing the harm in lust … in hatred … in delusion, I teach the abandoning of lust … hatred … delusion….

Indeed, this Noble Eightfold Path, that is, right view … right concentration, is the path, is the way of practice, to abandon lust, hatred and delusion.18

A. I. 216.

Monks, considering personal wellbeing, you should accomplish it with care. Considering others’ wellbeing, you should accomplish it with care. Considering the wellbeing of both, you should accomplish it with care. {542}

S. II. 29.

Here are definitions for these three kinds of benefits (attha):19

-

Attattha: personal benefit; the realization of personal goals, that is, the three goals (attha) mentioned earlier, which have to do with oneself, which are accomplishments specific to an individual. This factor emphasizes self-reliance at every stage of spiritual practice, so as not to be a burden on others or a hindrance to the community. Instead, one is fully prepared to help others and to engage in activities effectively. The mainstay for realizing this benefit is wisdom. There are many teachings for achieving this benefit, for example the ’ten virtues which make for protection’ (nāthakaraṇa-dhamma; ’virtues which make for self-reliance’). Broadly speaking, this factor refers to bringing the practice of the threefold training to completion in regard to personal responsibilities.

-

Parattha: the benefit of others; fostering self-reliance in others; helping others to realize wellbeing or to achieve spiritual goals, that is, the three goals (attha) mentioned earlier, which have to do with other people, which are accomplishments of those apart from oneself. The mainstay for realizing this benefit is compassion. The teachings promoting this benefit include the Four Principles of Service (saṅgaha-vatthu) and the teachings on the responsibilities of a virtuous friend (kalyāṇamitta).

-

Ubhayattha: the benefit of both parties or the shared benefit; the three goals (attha) mentioned earlier, which are realized by both oneself and others, or by oneself and one’s community, for example advantages accrued by way of shared belongings or by way of communal activity. In particular, this benefit refers to a social environment and way of life that is conducive for all members of a community to practise in order to realize personal benefits and to act for others’ benefit. The mainstays for realizing this benefit are moral discipline (vinaya) and communal harmony (sāmaggī). The teachings relevant to this subject include the Six Virtues Conducive to Communal Life (sārāṇīya-dhamma), the Seven Conditions of Welfare (aparihāniya-dhamma), along with general teachings on necessary conduct supportive to society.

These two triads of benefits or goals (attha) can thus be combined as a single group:

-

Attattha: personal benefit can be divided into three levels:

-

Diṭṭhadhammikattha: immediate benefit; basic or visible goals.

-

Samparāyikattha: future benefit; higher or profound goals.

-

Paramattha: supreme benefit; highest goal.

-

-

Parattha: the benefit of others can be divided into the same three levels:

-

Diṭṭhadhammikattha: immediate benefit; basic or visible goals.

-

Samparāyikattha: future benefit; higher or profound goals.

-

Paramattha: supreme benefit; highest goal.

-

-

Ubhayattha: the benefit of both oneself and others, or collective goals; every sort of benefit or objective (according to the three levels above: immediate, future, and supreme) that is supportive for developing and realizing personal wellbeing and the wellbeing of others. {543}

This section pertaining to the various benefits of life is naturally linked to the previous section on living the holy life. We can thus recapitulate the meaning of the holy life (brahmacariya), or Buddhist conduct (cariya), thus: a system of spiritual practice based on an understanding of natural truths, which is conducive to fulfilling worthy aspirations of human life, and which fosters both a way of life and a social environment supportive of realization.

In short, it is a way of life based on truth, leading to worthy goals and nurturing a healthy environment for realizing these goals.

The Path as the Threefold Training or as the Practice for Generating Noble Beings

Monks, there are these three trainings. What three? The training in higher virtue, the training in higher mind, and the training in higher wisdom.

And what is the training in higher virtue? Here, a monk in this Dhamma and Discipline is virtuous, restrained by the restraint of the Pāṭimokkha, perfect in conduct and resort, seeing danger in the slightest faults. He undertakes and trains in the various training rules. This is called the training in higher virtue.

And what is the training in higher mind? Here, secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unwholesome states, a monk enters and dwells in the first jhāna, which is accompanied by initial and sustained thought, with rapture and happiness born of seclusion. With the subsiding of initial and sustained thought he enters and dwells in the second jhāna, which has internal clarity and unification of mind, is without initial and sustained thought, and has rapture and happiness born of concentration. With the fading away as well of rapture, he dwells equanimous, mindful and clearly comprehending, experiencing happiness with the body; he enters and dwells in the third jhāna of which the noble ones declare: ’He is equanimous, mindful, one who dwells happily.’ With the abandoning of pleasure and pain, and with the previous passing away of joy and sadness, he enters and dwells in the fourth jhāna, which is neither painful nor pleasant and includes the purification of mindfulness by equanimity. This is called the training in higher mind.

And what is the training in higher wisdom? Here, a monk understands as it really is: ’This is suffering. This is the origin of suffering. This is the cessation of suffering. This is the way leading to the cessation of suffering.’ This is called the training in higher wisdom.

A. I. 235-6.

Friend Visākha, the three divisions of training principles are not included in the Noble Eightfold Path, but the Noble Eightfold Path is included in the three divisions of training principles. Right speech, right action, and right livelihood – these qualities are included in the division of virtue (sīla-khandha). Right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration – these qualities are included in the division of concentration (samādhi-khandha). Right view and right intention – these qualities are included in the aggregate of wisdom (paññā-khandha). {544}

M. I. 300-301.

The Noble Path and the Threefold Training

From the Eightfold Path to the Threefold Training

The threefold training is considered a complete system of practice, which encompasses the entirety of the Eightfold Path and distils the essence of the Path for the purpose of practical application. It is thus used as the standard teaching for describing Dhamma practice.

It is fair to conclude that the Eightfold Path contains the full essence of Dhamma practice, and the threefold training expresses the entirety of Dhamma practice in a practical way. Moreover, the threefold training draws upon the essential principles contained in the Path and elaborates upon them, providing comprehensive details of practice.

The Path (magga), or the Noble Eightfold Path (ariya-aṭṭhaṅgikamagga), can alternatively be translated as the ’Eightfold Path of Noble Beings’, ’Eightfold Path Leading One to Become a Noble Being’, ’Eightfold Path Discovered by the Noble One (the Buddha)’, or the ’Supreme Path Comprising Eight Factors’. The eight factors are as follows:

-

Right view (sammā-diṭṭhi; right understanding).

-

Right thought (sammā-saṅkappa).

-

Right speech (sammā-vācā).

-

Right action (sammā-kammanta).

-

Right livelihood (sammā-ājīva).

-

Right effort (sammā-vāyāma).

-

Right mindfulness (sammā-sati).

-

Right concentration (sammā-samādhi).

The term ’eightfold path’ leads some people to misunderstand that there are eight separate paths which must be travelled in succession: once one has completed one path one then begins another until all eight are complete. They think that one must practise these eight factors separately and in chronological order. But this is not the case.

The term ’eightfold path’ clearly refers to a single path with eight factors. This is similar to a perfectly built road, which possesses many different elements and components, for example: layers of earth, stones, gravel, sand, concrete, and tarmac to build up the road’s surface; the road’s borders; the lanes; banks where the road curves; light signals; road signs indicating direction, distance and location; road maps; and street lamps.

Just as a road is composed of these different parts and someone driving on it relies on all of them together, so too, the Path comprises eight factors and a Dhamma practitioner must apply all of them in an integrated fashion. {545}

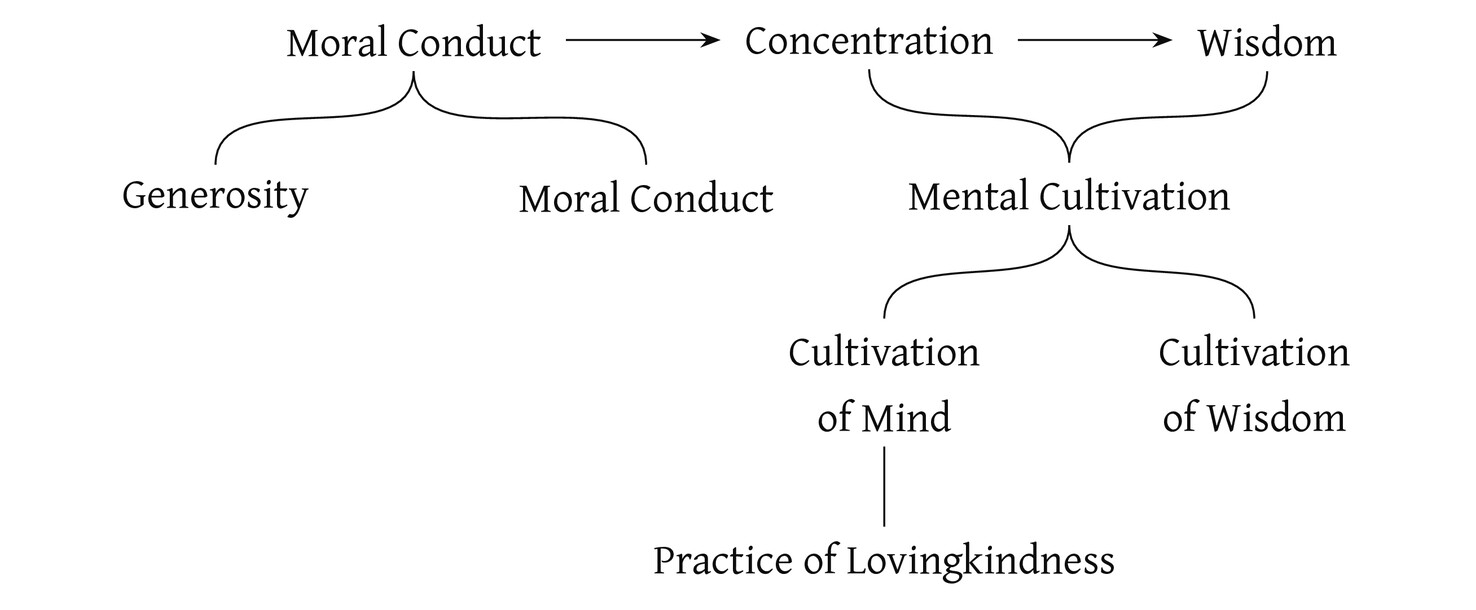

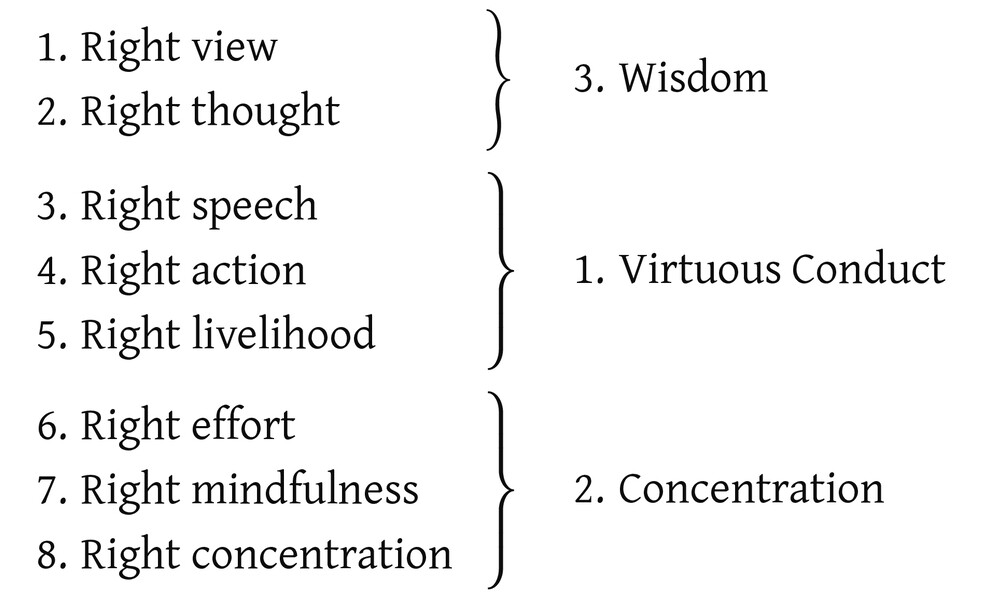

For ease of understanding the Buddha classified the eight Path factors into three groups or ’aggregates’ (khandha; dhamma-khandha). These are called the morality group (sīla-khandha), the concentration group (samādhi-khandha), and the wisdom group (paññā-khandha), or simply: virtuous conduct (sīla), concentration (samādhi), and wisdom (paññā). (See Note Three Groups)

Here, right speech, right action, and right livelihood are included in the morality group, just as one may distinguish the compressed earth, gravel, sand, etc., which make up the road’s surface, as one group. Right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration are included in the concentration group, as one may classify the road’s border, embankments, lanes, and curves – those things regulating the road’s course and direction – as another group. Finally, right view and right thought make up the wisdom group, just as one may include traffic lights, signs, and street lamps into a third group. This is illustrated as follows:

See the passage cited above: M. I. 300-301; cf.: A. I. 124-5, 295; A. III. 15-6; A. V. 326-7; see also the classification of five groups or aggregates (including those things beyond moral conduct, concentration and wisdom, making for two more factors: the liberation aggregate – vimutti-khandha – and the knowledge and vision of liberation aggregate – vimuttiñāṇadassana-khandha) at: D. III. 279; A. III. 134-5, 271; AA. V. 4; NdA. I. 90.

This classification of the three groups (the ’three dhamma-khandha’) – sīla-khandha, samādhi-khandha, and paññā-khandha – is a way of grouping similar qualities together.

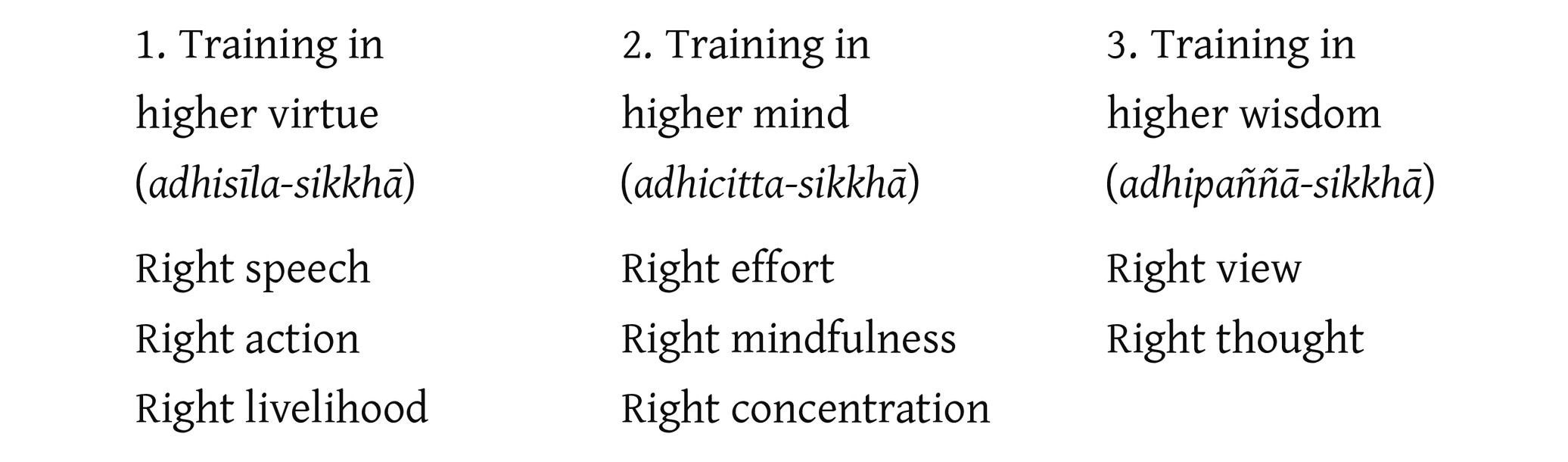

In regard to practical application, these Path factors are classified in a similar way, and as a group they are given the name the ’threefold training’ (tisso sikkhā). Individually, they are referred to as the training in higher virtue (adhisīla-sikkhā), the training in higher mind (adhicitta-sikkhā), and the training in higher wisdom (adhipaññā-sikkhā).

Both of these two groups can be referred to simply as sīla-samādhi-paññā. (Roughly speaking, adhisīla equals sīla, adhicitta equals samādhi, and adhipaññā equals paññā.)20 These trainings can be illustrated as follows: {546}

Whereas the classification of the three aggregates simply groups together similar qualities, the threefold training aims to show the sequence of how these qualities are applied in practice.

The word sikkhā can be translated as ’training’, ’study’, ’discipline’, ’paying careful attention to’, ’practice’, or ’cultivation’. (See Note Generating and Developing) This term refers to the essential aspects of training and cultivating one’s physical conduct, speech, state of mind, and wisdom, leading gradually to the realization of the highest goal, to liberation: Nibbāna.

A very similar Pali word to sikkhā is bhāvanā, which is translated as: ’generating’, ’developing’, ’cultivation’, ’growth’, or ’practice’.

Occasionally, one finds a similar threefold division of bhāvanā: development of the body (kāya-bhāvanā), development of mind (citta-bhāvanā), and development of wisdom (paññā-bhāvanā) – see D. III. 219-20. The commentaries, however, say that this passage refers to physical, mental and wisdom development completed by arahants (DA. III. 1003). Normally, the completed development of arahants is divided into four factors, with the development of virtue (sīla-bhāvanā) constituting the second one, and in this context the term bhāvita is most often used: bhāvita-kāya, bhāvita-sīla, bhāvita-citta, and bhāvita-paññā.

Brief definitions for the three trainings are as follows:21

-

Training in higher virtue (adhisīla-sikkhā):22 training and study on the level of conduct and in line with a moral code, in order to be upright in body, speech, and livelihood.

-

Training in higher mind (adhicitta-sikkhā):23 training the mind, cultivating spiritual qualities, generating happiness, developing the state of one’s mind, and gaining proficiency at concentration.

-

Training in higher wisdom (adhipaññā-sikkhā): training in higher levels of wisdom, giving rise to thorough understanding, which leads to complete purification of the mind and liberation from suffering.

In order to give a complete definition of these three trainings one must combine an explanation of their purpose. The threefold training refers to the training of conduct, the mind, and wisdom, which leads to an end of suffering and to true happiness and deliverance. The essence of each training in the context of this path of liberation is as follows:

-

The essence of training in higher morality is to live in an upright way in society, supporting, protecting, and promoting a peaceful and virtuous coexistence. Moral conduct is a foundation for developing the quality of one’s mind and cultivating wisdom.

-

The essence of training in higher mind is to develop and enhance the quality and potential of the mind, which supports living a virtuous life and is conducive for applying wisdom in the most optimal way.

-

The essence of training in higher wisdom is to discern and understand things according to the truth, to penetrate the nature of conditioned phenomena, so that one lives and acts with wisdom. One knows how to relate to the world correctly and shares blessings with others, endowed with a bright, independent, and joyous mind, free from suffering.

The essence of the threefold training is not confined to an individual, but also has a bearing on or appeals to people’s responsibilities in the context of their communities and society: to establishing social systems, building institutions, arranging activities, and applying various methods in order for the essence of these trainings to be integrated in society, or for people to be grounded in the threefold training. (Here, a moral code acts as a basis for these social systems, which then links to the training in higher morality.) {547}

Broadly speaking, when the term sīla encompasses a moral code or discipline, the meaning of sīla includes creating an environment, both physical and social, which helps to prevent evil, unskilful actions and promotes virtuous actions. This is especially true in relation to setting up social systems and social enterprises, by establishing communities, organizations, or institutions, and by enacting a moral code and prescribing rules and regulations, for regulating the behaviour of people and promoting communal wellbeing. The technical word for such a moral code is vinaya.

Strictly speaking, setting down a moral code (vinaya) is a preparation or an instrument for establishing people in virtuous conduct (sīla); technically, vinaya has not yet reached the stage of sīla. But as mentioned above, in relation to spiritual training, moral discipline is connected to and is a foundation for moral conduct. So, when speaking comprehensively, vinaya is included in the term sīla.

A moral code should be prescribed appropriate to the objectives of a particular community or society. For example, the monastic discipline (Vinaya) that the Buddha laid down for both the bhikkhu and bhikkhuni communities contains both precepts dealing with monks’ and nuns’ individual behaviour, and those dealing with communal issues: administration, looking into and considering legal issues, imposing penalties, appointing sangha officials, procedures for sangha meetings, proper decorum for both receiving visitors and for being a guest oneself, and the use of communal possessions.24

In the context of the wider society the Buddha suggested broad principles to be used by leaders and rulers, who should determine the details of behaviour in relation to their state or nation. An example is the teaching on the ’imperial observances’ (cakkavatti-vatta), which presents principles for a king or emperor to rule in a righteous fashion favourable to all members of the population, to prevent lawlessness, immorality and evil in the country, and to distribute wealth so that none of the citizens are left destitute.25

In contemporary parlance a disciplinary code (vinaya) fostering virtuous conduct (sīla) in society as a whole encompasses many aspects, including: the government, legislature, and judiciary; the economy, cultural traditions, social institutions; and other important aspects, like the policy around adult entertainment centres, places of ill-repute, addictive substances, crime, and professional standards.

Essentially, ’higher mind’ (adhicitta) or concentration refers to methods of developing tranquillity (samatha) and to various methods of (tranquillity) meditation, which many teachers and meditation centres have designed and established in the evolution of Buddhism, as is evident in the meditation systems described in the commentaries,26 which have been adapted over the ages. But in a general, comprehensive sense, higher mind or concentration encompasses all the methods and means to induce calm in people’s minds, to make people be steadfast in virtue, and to rouse enthusiasm and generate perseverance in developing goodness. {548}

From a broad perspective, similar to including vinaya in the term sīla, the training in higher mind includes a system of establishing virtuous friends (kalyāṇamitta), of providing for the seven favourable conditions (sappāya, see Note Favourable Conditions), and of enhancing the quality of the mind so that people progress in meditation and in mind development. This includes such things as: establishing places that are relaxing and refreshing; creating a cheerful, bright atmosphere in people’s living spaces, offices, and worksites; educating people to think in positive ways; instilling in people’s minds the qualities of lovingkindness and compassion, the desire to do good, and a wish for spiritual refinement; organizing activities that help generate virtue; encouraging people to adopt a spiritual ideal; and teaching people to strengthen the mind and increase its capability.

The sappāya (conditions that make for a sense of ease; suitable, supportive, and favourable factors; conditions favourable to meditation; conditions which strengthen and support concentration) appear in separate passages in the Tipiṭaka. The commentaries compile these factors into seven:

dwelling (āvāsa/senāsana);

resort; place for finding food (gocara);

speech; listening to teachings (bhassa/dhammassavana);

persons (puggala);

food (bhojana/āhāra);

climate, environment (utu); and

posture (iriyāpatha).

If these factors are unsuitable and unfavourable they are referred to as asappāya.

See: Vism. 127; VinA. II. 429; MA. IV. 161.

In a strict, literal sense, ’higher wisdom’ (adhipaññā) refers to the development of insight (vipassanā-bhāvanā), for which the systems of practice have evolved in a similar way to methods of practising concentration. But from a wider perspective, which takes into account the essence and objective of wisdom, this level of practice refers to all activities of developing one’s thinking and knowing, encompassing the entire spectrum of what is called ’study’ or ’training’. Such study relies on virtuous friends, especially one’s teachers, to transmit ’learning’ (suta; knowledge) and proficiency in the arts and sciences, beginning with vocational knowledge (which is a matter of virtuous conduct – sīla).

Vocational or academic knowledge in itself, however, does not qualify as adhipaññā. Teachers should establish faith in their students and encourage them to think for themselves; at the very least the students should develop right view in line with Dhamma. Over and above this, teachers can help students to see things according to the truth and to relate to the world correctly, to live wisely, to develop an effective practice that subdues defilements and dispels suffering, to benefit others, and to be happy.

Generally speaking, providing a training on this level is the function of schools or institutes of learning. Such places should support a training on all three levels: virtuous conduct, concentration, and wisdom; they should not focus exclusively on wisdom. This is because the training in higher wisdom is the highest stage of training, the completion of which relies on the first two stages as a foundation. Moreover, these three levels of training are mutually supportive. Only when these three stages of development are well-integrated is spiritual practice true and complete.

In everyday circumstances, the gradual and interrelated practice according to the threefold training is easy to illustrate. For example: when people live together peacefully they do not need to experience mistrust or fear; when one does not perform bad deeds the heart is at ease; when the heart is at ease one is able to reflect on and understand things effectively. When one does not perform bad deeds one is self-confident and the mind is settled; when the mind is settled one is able to contemplate things earnestly and directly. When one performs good deeds, say by helping someone else, the mind is joyful and clear; when the mind is clear one’s thinking too is clear and agile. When there are no issues of enmity and revenge between people, the mind is not overcast or in conflict; when the mind is not clouded or bad-tempered one contemplates things clearly, without bias and distortion. From such well-prepared foundations a person is able to develop more refined levels of spiritual practice. {549}

Householders Cultivate the Path by Developing Meritorious Actions

As mentioned earlier, when teaching the Dhamma in a suitable way for laypeople or householders, rather than apply the system of the Path in the form of the threefold training – sīla, samādhi and paññā – the Buddha reformatted the practice, as if establishing a simpler form of training. Here, he set down a new sequence of basic principles referred to as ’meritorious action’ (puñña-kiriyā) or the ’bases of meritorious action’ (puññakiriyā-vatthu). In this teaching, there are likewise three factors, but with different names: generosity (dāna), virtuous conduct (sīla), and mental cultivation (bhāvanā).

It is useful to understand that, similar to the threefold training, the teachings on meritorious action are also a form of study and training. Indeed, the essence of meritorious action is spiritual training.

Monks, there are these three grounds for meritorious action: … the ground for meritorious action consisting of generosity, the ground for meritorious action consisting of virtue, and the ground for meritorious action consisting of cultivation.

[One who desires the good] should train in acts of merit, which have far-reaching effects and end in bliss.

Let him practise generosity, righteous behaviour (samacariyā),27 and a heart of lovingkindness.

A wise person who cultivates these three qualities leading to happiness,

Attains a world of joy, free from misery.28

It. 51-52.

In this passage, after the Buddha mentions the three bases of meritorious action, he concludes by describing what one should do in regard to them, that is, ’one should train in acts of merit.’ Here, the Pali states: puññameva so sikkheyya. Combining these two terms results in the compound puñña sikkhā: ’training in merit’.

Training here refers to generating, developing, and becoming proficient in spiritual qualities, i.e. to advance on the Path in a way consistent with the teaching on the threefold training. Applying the threefold training as a standard, one can compare these teachings as shown on Figure Applying the Threefold Training.

As mentioned above, the teaching on meritorious actions for householders emphasizes a person’s external environment and elementary forms of spiritual practice. This is in contrast to the teachings aimed at the monastic sangha which emphasize a person’s inner life and higher levels of practice.

In the threefold training the beginning stages of practice are incorporated in the term sīla. The teaching on meritorious actions, however, stresses the way a person deals with material belongings and engages with society, and therefore the beginning stages are divided into two factors, with the management of material things – by way of generosity – reinforcing the second factor of virtuous conduct. For monks and nuns, the teaching begins with virtuous conduct; for householders it begins with generosity and virtue.

In other words, because monks and nuns do not have much to do with material things, generosity (dāna; ’giving’) plays a minor role. For this reason in the threefold training generosity is appended to or concealed within the factor of virtuous conduct. (On the allocation of material things in the monastic sangha look at the Vinaya.)

In regard to profound, internal factors the threefold training contains the two stages of concentration and wisdom. The monastic life is devoted to spiritual development, to the cultivation of higher mind (adhicitta) and higher wisdom (adhipaññā). The threefold training thus clearly separates spiritual training into these two factors. In contrast, the teaching on meritorious actions contains the single term ’cultivation’ (bhāvanā), and according to the passage above the focus here is on the practice of lovingkindness. {550}

The life of householders is directly involved with material possessions, and the search for and management of these possessions takes place in relation to society. If people do not manage their possessions well, they lose them, and both individuals and society is troubled. For this reason it is necessary to highlight the two factors of generosity and virtuous conduct, as two distinct meritorious actions. Although internal, spiritual practice is important, it needs to be managed in a way appropriate to people’s capabilities and available time and energy. Here, the two factors of mind training and wisdom development are combined in the single factor of ’cultivation’ (bhāvanā). And because the distinctive feature of the householder life is an interaction with the wider society, cultivation here focuses primarily on the practice of lovingkindness.