The Buddhist Teachings on Desire

Introduction

People sometimes express the following doubts and criticisms about Buddhism:

’Buddhism teaches one to abandon craving and to be free from desire. If people are without desire and don’t seek personal gains and wealth, how can the nation develop? Buddhism opposes progress.’

’Nibbāna is the goal of Buddhism and the practice of Dhamma is for reaching Nibbāna, but Buddhists should not desire Nibbāna, because if they do then they have craving and their practice is incorrect. If people have no desire, how can they practise? Buddhist teachings are contradictory and they teach to do the impossible.’

These doubts and criticisms seem to touch upon the entire scope of the Buddhist teachings, from the everyday life of householders to the practice for realizing Nibbāna, from the mundane to the transcendent. But in fact, they do not have a direct bearing on Buddhism at all. They stem from a confused understanding, both of human nature and of the Buddhist teachings.

These misunderstandings are prevalent even amongst Buddhists. They are connected to matters of language and terminology. In particular, people have heard that Buddhism teaches one to abandon taṇhā (’craving’), which is often translated as ’desire’. For whatever reason, they are not able to distinguish between these various terms and end up equating craving with desire; they believe that all forms of desire are forms of craving. Moreover, they believe that Buddhism teaches to abandon all desire – to be devoid of desire.

Furthermore, other Pali terms with similar connotations may have been translated in other ways (i.e. not as ’desire’). When the discussion of desire comes up, people may then forget to refer to these other terms for comparison.

For a clear understanding of Buddhism, this misunderstanding needs to be rectified. To begin with, craving (taṇhā) is a form of desire, but not all desire manifests as craving. There exists a positive form of desire, which is essential for Dhamma practice and spiritual cultivation.

Before examining this subject in more detail, let us examine some of the mechanisms of human activity. {972}

Mechanisms of Human Activity

One doubt frequently expressed is based on the belief that people’s actions must always be accompanied by desire; people act according to desire. If there were no craving or desire as a catalyst, people would not act. Surely, they would remain inert, listless, and apathetic.

To begin to reply to this doubt, all human actions, even the action to refrain from acting, requires some movement or activity in the mind. To be alive entails such movement and activity. Here, we can examine the mechanisms functioning behind such activity.

Human beings are not like the leaves and branches of trees, which sway in the breeze, affected solely by external conditions. Humans act prompted by internal conditions. When the physical body is healthy and ready for activity, the mind begins to be aware of what lies in front and behind, above and below, nearby and far away, along with the surrounding location of various objects. In short, one has an understanding of the possible avenues for movement and activity.

With this initial understanding, one must then decide which direction to move and how to act. The mental factor that controls or dictates this decision-making process is intention (cetanā).

Here, in this process, intention is affected by an impetus or motivation, which one can call ’desire’. When one desires to go somewhere, obtain something, or perform an action, intention chooses to fulfil this desire.

What is desire? On a basic level, desire stems from likes and dislikes. Whatever agrees with one’s eyes, ears, tongue, mind, etc., one wishes to obtain and consume. Whatever is disagreeable to the senses one wishes to escape from or get rid of. Intention makes decisions according to these likes and dislikes. This form of desire, based on preferences and aversions, is referred to as ’craving’ (taṇhā).

In sum, there are various factors involved in this activity: knowledge (paññā; ’intelligence’, ’wisdom’) helps to reveal and discern the various objects in one’s surrounding environment; craving (taṇhā) wishes to obtain or get rid of particular objects; and intention (cetanā) chooses to act according to these desires.

Yet there is another element to this process. Living beings possess deeper, more fundamental needs and desires when it comes to action or non-action. They wish to exist, to survive, to be safe, to be healthy and happy, and to live in an optimal state. They wish to exist in a state of fulfilment.

Here one may ask whether such fulfilment is found by merely relying on a knowledge of one’s surrounding sense objects, a craving to either consume or evade such objects, and an intention which propels actions in accord with the whispered suggestions by this very craving. {973}

Wisdom itself will answer that this is not enough. If one encounters some food that has been made to look appetizing by adding various chemical colorants, craving will want to consume it. But if one indulges craving, it is as if one drops poison into one’s food and one will suffer from obesity or some other ailment. This knowledge is insufficient and untrustworthy. It may claim to be wisdom (paññā), but in fact it is merely an expression of not-knowing (aññāṇa), i.e. of ignorance (avijjā).

Take the example of a student:

Counterfeit wisdom may say, ’Not far from here is a place of amusement and entertainment where one can really be wild and unconstrained.’ Craving, wishing to have fun, then grabs hold of this appealing prospect. It whispers, ’Don’t go off to school and tax yourself listening to some tiring subject.’ It then prods intention, which decides to skip school and engage in some form of excess or debauchery.

When wisdom has been developed as true understanding, besides being aware of one’s surroundings, one also knows how to bring about goodness, proficiency, and happiness. One knows what is beneficial and what is harmful, what to promote and what to avoid. One has an understanding of causes and effects, knowing that specific actions will have both short-term and longterm consequences.

In the case of the student, he knows that if he goes off to a place of vice and indulgence, he will only derive momentary pleasure, but in the long run his body, his family, and his intelligence will suffer. If, on the other hand, he perseveres in his studies all aspects of his life will improve.

Craving acts as the agent, hankering for this and that, while this bogus wisdom only has a dim understanding of these proceedings. Craving grabs hold of agreeable aspects and tells intention to seek gratification. This cycle, however, will never lead to true wellbeing.

When wisdom appears, it knows that following the stream of craving will lead to eventual danger and affliction, and the mechanism of ignorance-craving-intention is interrupted or abates.

Wisdom investigates and discerns the interrelationship between things. It knows, for instance, that happiness is based on good health. It recognizes that, in order to maintain good health, one should eat certain foods, exercise, set up a certain environment, maintain certain daily routines, cultivate the mind, allocate one’s time well, etc.

These things recommended by wisdom are of no interest to craving, which only seeks personal gratification, delight, ostentation, and distinction. And anything that is irritating or offensive, it wishes to escape from or eliminate.

It may appear that without the enticements by craving, there is no alternative motivating force prompting intention and instigating actions suggested by one’s understanding of surrounding circumstances. The functioning of life is impeded.

Yet there exists an alternative motivating force. In this context, people possess another innate need or desire. In everyday life, however, sense impressions by way of the five senses (eye, ear, nose, tongue, and body) tend to stand out. When one encounters a sense impression and feels either comfort or discomfort, delight or aversion, these feelings take precedence, leading to liking and disliking. {974} This is the path of craving. Craving wishes to acquire those things that are agreeable and to evade or eliminate those things that are disagreeable. Intention then steers life in this direction. If one leads a shallow or superficial life, resembling the life of an animal, one may aimlessly follow the promptings of craving until one’s dying breath.

For human beings, however, who have the potential for excellence and distinction, craving is not the sole motivating force. As mentioned above, we possess a more profound need or desire, namely: the desire for goodness, for a healthy life, for righteousness, for true and lasting happiness, and for fulfilment and integrity. This wish does not extend only to ourselves. Whatever one encounters and engages with, one wishes for that thing to reach its optimal state of completeness. And this wish is not a detached sentiment; one also wishes to actively help bring about this fulfilment and completeness.

This alternative motivation, which is inherent in everyone, is referred to in Pali as chanda (’wholesome desire’, ’wholesome enthusiasm’).

Here, the direction of one’s life changes course. One begins to develop the quality of one’s life. Wisdom (paññā) discerns what is harmful and what is beneficial in one’s surroundings, and recognizes the path to true fulfilment. Wholesome desire (chanda) aspires to this fulfilment and wishes to bring it about. And intention (cetanā) initiates the effort to move in this positive direction.

When people develop themselves in this way, the cycle of ignorance-craving-intention (avijjā-taṇhā-cetanā) is loosened or weakened. This cycle may also be referred to as ignorance-craving-unwholesome action (avijjā-taṇhā-akusala kamma).

It is replaced by the sequence of wisdom – wholesome desire – intention (paññā-chanda-cetanā), or wisdom – wholesome desire – wholesome action (paññā-chanda-kusala kamma), which eventually develops into the way of life of awakened beings.

When true wisdom comes to the fore, counterfeit wisdom (i.e. ignorance) retreats. Those things recommended by wisdom for promoting health and wellbeing are likely to be disagreeable in regard to craving. Craving likes to be indulged by ignorance. When wisdom appears, craving cannot sustain itself. This is where wholesome desire has an opportunity.

When wisdom points out that true fulfilment is possible, and that specific things are valuable for one’s life and should be cultivated, wholesome enthusiasm (chanda) takes over this matter from wisdom. It then persuades intention to direct the necessary actions to reach such fulfilment.

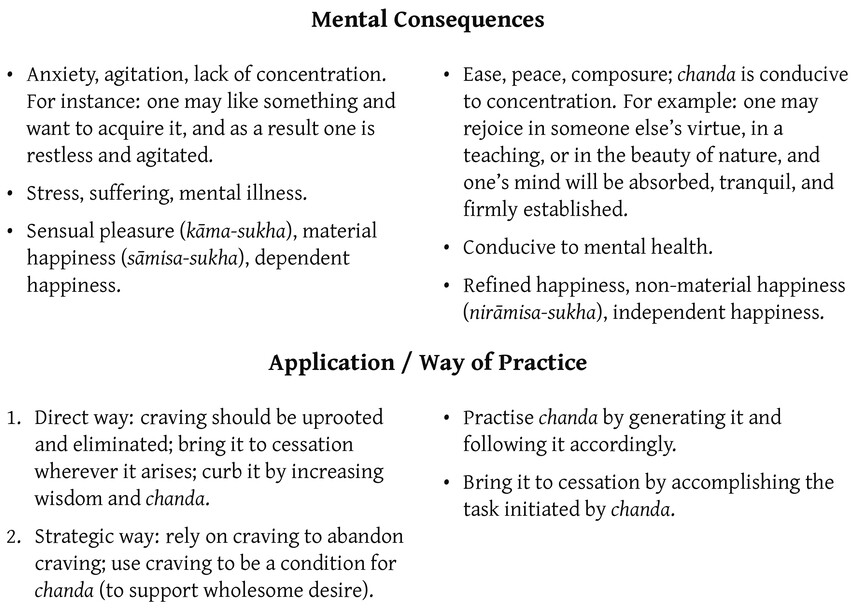

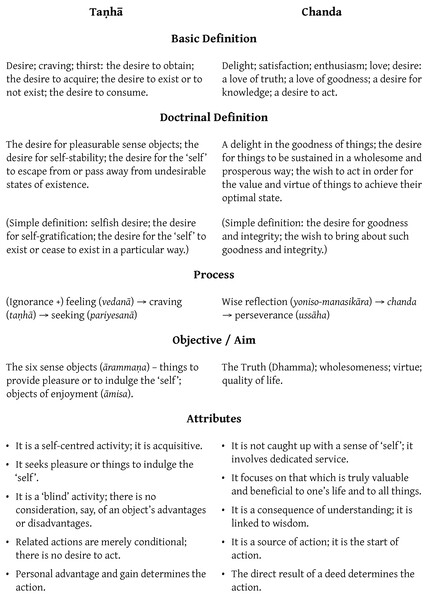

In sum, there are these two distinct kinds of desire: craving (taṇhā) and wholesome enthusiasm (chanda).

There is another important element to this process. In the cycle of ignorance and craving, as soon as a feeling of pleasure or displeasure arises, along with the desire to obtain or consume, a sense of self appears to act as the delegate or representative. A ’consumer’ or ’owner’ is born. This then creates the duality between such a consumer or owner and those objects desired and consumed. (Following on from this is the arising of a sense of ’you’, of ’him’, ’of them’, etc, who threaten, obstruct, compete, etc.) {975}

On a deeper level, one wishes for this so-called self to be stable, so that one can continue to consume things. And one wishes for it to be powerful, so that one is ensured of obtaining and consuming things to the greatest degree, without any interference. At the same time, if one encounters unpleasant, undesirable things, one wishes to escape from or eliminate them. And if one finds the situation unendurable, one may react by desiring some form of self-annihilation.

The dual process of wisdom and wholesome desire is the opposite. The desire for things to exist in the optimal state of goodness and integrity requires no sense of self to intervene. There is no need for an owner, a consumer, a desirer, etc. One acts simply in accord with nature.

To sum up once again, there are these two kinds of desire acting as motivating forces for people to act:

-

Craving (taṇhā): the desire to consume and to acquire; the desire for self-gratification; the desire for oneself to exist or not exist in some particular way; selfish desire.

-

Wholesome desire (chanda): the delight in witnessing the fulfilment and integrity of things; the desire to help bring about such fulfilment; the desire for things to be complete in themselves.

Wholesome desire includes the wish for self-fulfilment and self-integrity. For example, one wishes for one’s body to exist in a state of good health. In this case, one wishes for the various organs of the body to exist in their own natural state of wellbeing. (How does this desire compare with the craving for physical beauty and attractiveness? This question invites the wise inquiry from discriminating individuals.)

Contrasting Aspects of Craving and Wholesome Desire

Non-action as a Form of Action

As mentioned above, people act according to their knowledge and understanding, which may simply be at the level of responding to sense stimuli, or it may develop into true wisdom, which is able to determine what is appropriate and inappropriate.

In many circumstances, however, instead of initiating an action, people pause, baulk, or stop short. In this case, the hesitation, passiveness, or inaction is a form of action, and it may be a potent form of action at that. As will be explained below, craving (taṇhā) initiates actions that are prerequisites for acquiring objects of gratification or for protecting the stability of one’s cherished sense of self. Here, the term ’action’ includes non-action.

There are many reasons why craving may initiate non-action. For example, one may refrain from acting because by acting one would be deprived of some pleasure that one is currently experiencing, or because one would encounter some kind of trouble or adversity.

Even in the case that acting in a particular way would be truly beneficial for one’s life, craving may urge one to refrain from acting out of fear of hardship or deprivation. {976}

When people develop wisdom and generate wholesome desire as a motivating force, they perform actions they recognize as appropriate and valuable, even though by acting they will face discomfort and be resisting the urge by craving to refrain from acting. Conversely, craving may prompt acting in order to obtain some pleasure, but wisdom, by discerning that such action will damage one’s quality of life, will urge one to refrain.

When people’s wisdom increases but refined forms of craving remain, these two qualities become intertwined and profit from one another. The behaviour of wise individuals is thus more complicated than that of other people. The important issue here is which factor gains the upper hand: does craving or wisdom direct proceedings?

If one applies continual wise reflection, wisdom takes the leading role and becomes increasingly sharper. It ushers in wholesome desire as the driving force for directing one’s life, to the extent that craving ceases.

Here one can see that by removing the factor of craving from the equation, human actions still proceed. Moreover, they are enriched.

Formerly, one relied on craving to help protect the sense of self. Now, wisdom guides one’s life and paves the way for wholesome desire. As a consequence, one is released from the clutches of craving.

Means and Ends: Craving as a Motivating Force

When one gets to the heart of the matter, one recognizes that craving (taṇhā) in fact is not a genuine motivation for action, because the act itself is not the priority for craving.

As mentioned above, craving desires to consume and acquire things that provide one with pleasure. Wholesome desire (chanda), on the other hand, wishes for true completion and fulfilment of all things with which one engages. This dichotomy provides for complexity in regard to action and non-action.

For example:

Sarah is endowed with wholesome enthusiasm. She sees the interior of a house and wants it to be clean (she wishes for this dwelling to exist in a state of completeness). If it is dirty, she wishes for it to be clean and picks up a broom to sweep the floor. She derives joy and contentment both from sweeping (which is the cause for the desired result) and from witnessing a clean space (which is the direct result from sweeping).

Harry has no interest or delight in cleanliness, but he does have a sweet tooth. His mother suggests that he helps with the chores, but he doesn’t respond. She thus says, ’If you sweep the house, I will buy you some sweets.’ When he hears this, Harry picks up a broom and sweeps. In fact, Harry does not desire cleanliness. He only sweeps because this action is a means by which he can get some candy.

Harry derives no pleasure from sweeping (he may even find it irritating) and he is not determined to do a good job (his mother may need to constantly supervise him). This is because sweeping is the cause for a clean house, which is not the result he desires. {977} His happiness will have to wait until he gets the sweets.

To reiterate, craving does not desire the thing or state that is the direct result of an action. Craving urges action only in the case when it is a necessary prerequisite for obtaining desired objects. If there is another way to obtain the desired objects without needing to make effort, craving will prompt one to avoid acting and choose the path of inaction instead. Craving is more often a motivation for inaction than it is for action.

When craving leads to an avoidance of action, it may manifest in the form of laziness, whereby one clings to pleasurable sensations. Alternatively, it may manifest in the form of fear, say by being afraid of encountering some form of discomfort while performing an action or being anxious of losing self-importance.

When inaction is needed for craving to get what it wants, that is, increased sensual pleasure or reinforced self-importance, craving urges such inaction, without considering whether positive effects derived from acting may be forfeited.

Here are more examples: a child refuses to go to school because he knows that his mother will then increase his allowance for sweets (this is a clear case of inaction being a potent form of action); a man finishes work early in order to drink alcohol and gamble; someone receives a bribe in order to refrain from work that should be done; out of laziness, one pays someone else to do some tasks that one should attend to oneself. In this case, one forfeits the satisfaction and delight that is connected to the fruits of one’s own labour.

Positive action is initiated by wholesome desire (chanda) stemming from wisdom, which recognizes what is truly valuable and what should be done. Wisdom rouses wholesome desire for bringing these things to completion.

Even in the case when craving initiates action, there are perils, because the preconditions mentioned earlier establish the following equation: craving urges action out of delight for the pleasure derived from such action. The more one acts the more pleasure one receives; the more pleasure there is the more one desires; the more one desires the more one acts. In many occasions people keep acting until the positive results of these actions are squandered.

Wholesome desire, on the other hand, initiates action out of delight for its positive and wholesome effects. The more one acts the more these positive effects increase and the more delight one experiences; the more delight one has the more one acts. One continues acting until the goodness and integrity reaches completion. The action fully corresponds with its objective.

In sum, craving more often than not urges inaction, and even when it initiates action, these actions are hazardous and lead to more harmful effects than beneficial ones. One should thus abandon craving and, instead, foster wisdom and cultivate wholesome desire. {978}

Formal Basis for the Principles of Desire

Linguistic Analysis of the Term Chanda

As mentioned earlier, the confusion surrounding the meaning of desire, which is viewed in an overly restrictive sense by associating all desire with craving, stems from an erroneous and inadequate understanding of some key Pali terms.

There are many Pali terms denoting desire, and some of these terms are complex both in terms of their definitions and how they are used in speech and writing. This complexity invites confusion.

First, let us distinguish and clarify some of these difficult terms.

The Pali word which is used in both a general sense, covering the entire spectrum of desire, and in a technical sense, referring specifically to wholesome desire, is chanda.

Chanda may be translated in many different ways, including: will, desire, delight, enthusiasm, zeal, contentment, satisfaction, aspiration, yearning, wish, love, and passion. At this point, let us simply refer to it as ’desire’.

Drawing from different sources, the commentaries mention three kinds of desire (chanda):1

-

Taṇhā-chanda: desire as craving (taṇhā); unwholesome desire.

-

Kattukamyatā-chanda: the desire to act; the wish to act. Occasionally, this term is used in a neutral sense, applicable to both wholesome and unwholesome contexts, but generally it is used in a positive, wholesome sense.

-

Kusaladhamma-chanda: desire for virtuous qualities; wholesome desire for truth. It is often abbreviated to kusala-chanda (love of virtue; aspiration for goodness) or dhamma-chanda (love of truth; aspiration for truth).

Taṇhā-chanda:2 the term chanda in this context is a synonym for craving (taṇhā), in the same way as the terms rāga (’lust’) and lobha (’greed’).3 This form of chanda is found frequently in the Pali Canon, including in the term kāma-chanda (’sensual desire’), which is the first of the five hindrances (nīvaraṇa) and is equivalent to kāma-taṇhā (’craving for sensuality’).4 {979} Chanda in this context is usually used on its own, but sometimes it is used together with synonyms, for example in this passage by the Buddha:

With the relinquishment of desire (chanda), lust (rāga), delight (nandi), craving (taṇhā), and clinging (upādāna) … regarding the eye, forms, eye-consciousness, and things cognizable through eye-consciousness, I have understood that my mind is liberated. (This passage refers to all six sense bases.) (See Note Synonyms of Desire)

M. III. 32.

Because chanda in this context is identical to taṇhā, it is possible to replace the term chanda with the term taṇhā in the following passages: ’a desire for existence’,5 ’a desire for sense pleasures’,6 ’delight for the body’,7 ’love of sexual intercourse’,8 ’delight in the body and feelings, which are impermanent, unsatisfactory, and insubstantial’,9 and ’desire for sounds, smells and tastes, which are impermanent, unsatisfactory, and insubstantial’.10

Compound words are created with chanda in a similar way to taṇhā, for example: rūpa-chanda (’delight in forms’), sadda-chanda (’delight in sounds’), gandha-chanda (’delight in smells’), rasa-chanda (’delight in tastes’), phoṭṭhabba-chanda (’delight in tactile objects’), and dhamma-chanda (’delight in mental objects’).11 Chanda can be used in the context of human relationships,12 referring to love or affection, as is seen in the Gandhabhaga Sutta, where it refers to love for one’s wife and children.13 In this same sutta it states: ’Chanda is the root of suffering,’ in the same manner as the second noble truth, which states that craving is the cause for suffering. In another sutta the Buddha says that one should abandon chanda (for things that are impermanent, dukkha, and not-self),14 in the same way that in the Dhammacakkapavattana Sutta he says that one should abandon craving.15

The commentaries generally classify chanda, rāga, nandi, and taṇhā as synonyms for one another, but in some necessary cases a distinction is made according to the intensity of desire.

For example, chanda is described as a weak form of taṇhā or a weak form of rāga, but when it arises frequently it becomes an intense form of craving or greed.

Similarly, chanda is a weak form of lobha, but when desire intensifies and leads to infatuation, it is classified as rāga, and when it further intensifies it becomes acute greed (chanda-rāga).

See: DA. II. 499; AA. IV. 190; SA. III. 64; VinṬ.: Verañjakaṇḍavaṇṇanā, Paṭhamajjhānakathā; VismṬ.: Pathavīkasiṇa-niddesavaṇṇanā, Paṭhamajjhānakathāvanṇṇanā.

Kattukamyatā-chanda: the desire to act. This form of desire is equivalent to the group of mental factors (cetasika) classified in the Abhidhamma as ’miscellaneous’ or ’apportioned’ (pakiṇṇaka-cetasika), that is, they can arise in both a wholesome mind state and in an unwholesome mind state.16

The kattukamyatā-chanda most familiar to students of Buddhism is the desire or enthusiasm (chanda) classified as the first factor in the Four Paths to Success (iddhi-pāda),17 and which is also the essential quality in the Four Right Efforts (sammappadhāna).18 The meaning of kattukamyatā-chanda is very similar to the meaning of viriya (’energy’), vāyāma (’effort’), and ussāha (’endeavour’). {980} These terms are occasionally used together to complement each other.19 This form of desire is considered an essential factor in Dhamma practice.

The commentaries tend to include this form of desire in the third form, of kusaladhamma-chanda, as if they are one and the same. For example, the desire in the Four Paths to Success and in the Four Right Efforts is classified as both kattukamyatā-chanda and kusaladhamma-chanda.20

Kusaladhamma-chanda: this form of desire is mentioned in one sutta, in which it is the final factor in a list describing the six things that are difficult to encounter in the world.21 It is considered an essential factor for people in order to benefit from the Buddhist teachings or to lead a virtuous life, because although one may have encountered the first five factors, if one lacks a desire for wholesome qualities one will not be able to truly benefit from these other factors:

Monks, the appearance of six things is rare in the world. What six?

The appearance of a perfectly enlightened Buddha is rare in the world;

the appearance of one who teaches the Dhamma proclaimed by the Buddha is rare in the world;

to be reborn in the land of the noble ones is rare in the world;

the possession of unimpaired physical and mental faculties is rare in the world;

the absence of foolishness and dimwittedness is rare in the world; and

a desire for wholesome qualities is rare in the world.

The chanda most frequently referred to in the context of Dhamma practice is desire and enthusiasm as found in the teaching on the Four Right Efforts (sammappadhāna; ’complete effort’):

That person generates desire for the nonarising of unarisen evil unwholesome states; he makes an effort, arouses energy, raises up the mind, and perseveres. He generates desire for the abandoning of arisen evil unwholesome states … for the arising of unarisen wholesome states … for the maintenance of arisen wholesome states, for their non-decline, increase, expansion, fulfilment, and development.

This passage is considered a definition of the Four Right Efforts. Here, wholesome desire (chanda) is designated as the essence or principal ingredient of effort (viriya), which is included in the thirty-seven factors of enlightenment (bodhipakkhiya-dhamma).

The term chanda in other passages related to Dhamma practice has a similar meaning, for example: the desire to fulfil all wholesome qualities,22 the desire to undertake training,23 the desire to develop the faculty of wisdom,24 the desire to abandon all mental impurities,25 and the desire for Nibbāna.26 {981}

Chanda in these cases should be interpreted as both kattukamyatā-chanda and kusaladhamma-chanda: as both the desire to act and the desire for virtuous qualities, or in brief: the desire to do good.27

The Vibhaṅga of the Abhidhamma defines chanda in the Four Right Efforts and in the Four Paths to Success as kattukamyatā-kusaladhamma-chanda:28

-

The Four Right Efforts: In the phrase ’generate chanda’, how is chanda interpreted? Whichever delight, aspiration, desire to act, or wholesome love of truth there is is called chanda.

Chandaṁ janetīti tatha katamo chando? Yo chando chandikatā kattukamyatā kusalo dhammachando ayaṁ vuccati chando.

-

The Four Paths to Success: In the Four Paths to Success what is the path to success of aspiration (chanda-iddhipāda)? At whichever time a monk in this Dhamma and Discipline cultivates the transcendent jhānas (lokuttara-jhāna) … the delight, aspiration, desire to act, or wholesome love of truth at that time is called chanda.

Tattha katamo chandiddhipādo? idha bhikkhu yasmiṁ samaye lokuttaraṁ jhānaṁ bhāveti … yo tasmiṁ samaye chando chandikatā kattukamyatā kusalo dhammachando ayaṁ vuccati chandiddhipādo.

This definition in the Vibhaṅga is the basis for later commentarial interpretations of chanda as a distinctively wholesome quality and is most likely the origin of the convention of combining kattukamyatā-chanda with kusaladhamma-chanda into a single factor.

Chanda as the Root of Suffering and Chanda as the Source of Wholesome Qualities

The Buddha used the single compound term chanda-mūlaka in different contexts, sometimes with opposite meanings: in one case it may refer to a wholesome quality and in another case to an unwholesome quality. It is useful here to examine this discrepancy.

The term chanda-mūlaka means having desire as the root, source, or point of origin. In one context the Buddha states that all forms of suffering have desire as the root, whereas in another context he states that all things have desire as the root. {982}

A. Desire as the root of suffering and of the five aggregates of clinging:

Headman, this matter can be understood in this way: ’Whatever suffering arises, all that arises rooted in desire, with desire as its source; for desire (chanda) is the root of suffering.’

S. IV. 329-30.

That bhikkhu delighted and rejoiced in the Blessed One’s statement. Then he asked the Blessed One a further question: ’But, venerable sir, in what are these five aggregates subject to clinging rooted?’ ’These five aggregates subject to clinging, bhikkhu, are rooted in desire (chanda).’

M. III. 16; S. III. 100-101.

These two passages correspond with one another, as confirmed by the Dhammacakkapavattana Sutta, in which the Buddha states:

’In brief, the five aggregates subject to clinging are suffering.’

S. V. 421.

All of the commentarial and sub-commentarial explanations of the second passage (on the five aggregates of clinging) are consistent, stating that ’rooted in desire’ means ’rooted in craving (taṇhā)’ or ’rooted in covetous desire (taṇhā-chanda)’.29 These texts occasionally confirm that these explanations are consistent with craving (taṇhā) being denoted as the origin of suffering (dukkha-samudaya).

B. Desire as the root of all things:

The Buddha uttered these words: Chandamūlakā … sabbe dhammā, which may be rendered as ’all things are rooted in desire’, ’all things are based on desire’, or ’all things have desire as their source’.

This key phrase by the Buddha is contained in a longer passage, which can be considered a compilation of ten major Buddhist principles. It contains important principles of Dhamma practice and culminates in the highest goal of Buddhism:

Monks, if wanderers of other sects should ask you: ’What, friends, are all things rooted in? … What is their culmination?’ you should answer them as follows:

All things are rooted in desire

(chandamūlakā … sabbe dhammā).All things have attention as their source

(manasikāra-sambhavā sabbe dhammā).All things originate from contact

(phassa-samudayā sabbe dhammā).All things converge upon feeling

(vedanā-samosaraṇā sabbe dhammā). {983}All things are headed by concentration

(samādhippamukhā sabbe dhammā).All things have mindfulness as their sovereign

(satādhipateyyā sabbe dhammā).All things have wisdom as their pinnacle

(paññuttarā sabbe dhammā).All things have liberation as their essence

(vimutti-sārā sabbe dhammā).All things merge into the deathless

(amatogadhā sabbe dhammā).All things culminate in Nibbāna

(nibbāna-pariyosānā sabbe dhammā).30A. V. 106-107.

If you are asked thus, monks, it is in such a way that you should answer those wanderers of other sects.

It is clear that all of these factors are vital in Buddhist practice. Together, they constitute the cultivation of wholesomeness up to the final goal of Buddhism, and these factors are thus all wholesome in themselves. At the very least, they are neutral factors, which may be incorporated in this wholesome framework. For this reason, the term ’desire’ (chanda) here definitely does not refer to an unwholesome quality.

The commentaries explain that ’all things’ (sabbe dhammā) here refers to the five aggregates, i.e. to all conditioned phenomena (saṅkhata-dhammā). (Nibbāna is excluded here as it is the cessation of all conditioned phenomena.)

Note that in the previous section (above) the five aggregates of clinging (upādāna-khandha) are said to be rooted in desire, and that this desire is equated with craving (taṇhā). Here, however, the five aggregates (i.e. not as a basis for clinging) are mentioned.

How do the five aggregates and the five aggregates of clinging differ from one another? The Buddha said that in the case that the five aggregates are a supportive condition for the mental taints (sāsava) and for clinging (upādāniya), they constitute the five aggregates of clinging. If they are free from the taints and from clinging they are the five aggregates in a sheer or absolute sense.31

Many sub-commentarial passages explaining these ten factors explicitly state that wholesome qualities are rooted in desire (chandamūlakā kusalā dhammā): wholesome desire (chanda) is the source of wholesome things. One of these passages defines this desire specifically as the ’desire to act’ (kattukamyatā-chanda), which incorporates the desire for virtuous qualities (kusaladhamma-chanda; this includes the love of goodness – kusala-chanda – and the love of truth – dhamma-chanda).32

Definitive Definition for Chanda

When we have considered the various definitions of the term chanda and thoroughly examined the divergent passages in which it is used, we are prepared to establish a definitive definition for this term. By relying on a mutual understanding of this term we can establish a standard definition for it in the context of Dhamma study.

In brief, the term chanda encompasses all forms of human desire. {984}

Unwholesome, negative chanda is equivalent to the term taṇhā. Because the term taṇhā is familiar to most students of Buddhism, negative desire may be replaced by this term.

Virtuous, wholesome chanda is called kusaladhamma-chanda; it is sometimes abbreviated to kusala-chanda or dhamma-chanda. As negative desire may be referred to as taṇhā, it is simple and convenient to refer to wholesome desire by the single term chanda.

Kattukamyatā-chanda (’the desire to act’) is a neutral form of desire. In most cases this term is used in a positive sense, referring to the desire for virtuous qualities (kusaladhamma-chanda). Therefore, it too may be incorporated into the single term chanda.

Here we can determine to simplify matters by using just these two terms to refer to human desire and motivation:

-

Taṇhā: unwholesome desire (the desire to consume, to acquire, and to obtain).

-

Chanda: wholesome desire (the desire to act; the desire to bring about integrity and fulfilment).

We can feel at ease by making this simple distinction, because it accords with an identical distinction made in the commentaries and later texts.

In many of the texts, when there is a passage relevant to the subject of unwholesome and wholesome desire, an analysis of these qualities is provided. Although this analysis is not always comprehensive, it is clear that the authors of these texts wished to point out the difference between these two kinds of desire. (Note that there is no single passage in which the three aforementioned kinds of desire are clearly listed together.)33 Occasionally, a pair of clearly defined terms is used; the most common distinction is as follows:

-

Taṇhā-chanda: desire as craving.

-

Kattukamyatā-chanda: the desire to act.

There are two commentarial texts which present a clear account of these principles dealing with desire. In the Papañcasūdanī and the Paramatthadīpanī, ’desire’ (here, the Pali term patthanā is used) may be classified into two kinds:34 (See Note Desire as Craving or Action)

-

Covetous desire; desire with craving (taṇhā-patthanā).

-

Wholesome desire (chanda-patthanā).

These commentaries refer to examples from the Pali Canon. In the Buddha’s teaching: For him who still desires, there is obsessive desiring and agitation about those things on which he fixes his attention (Sn. 176), the desire referred to is craving (taṇhā).

In the teaching: I have cut off, destroyed, and cleared the stream of Māra the wicked one; you should greatly rejoice and desire true safety (M. I. 227), the desire referred to is chanda, which is a wholesome quality of desiring to act.

The commentaries also refer to this passage: A bhikkhu who is in higher training (sekha), who has not yet reached the fruit of arahantship, and who is still desiring the supreme security from bondage (M. I. 4). Here too, ’desire’ refers to chanda as a wholesome quality.

These commentarial explanations support the classification of desire into two distinct kinds. {985}

Craving and Wholesome Desire

As mentioned just above, there are two main motivating forces prompting human beings to act:

-

Taṇhā: pleasure, delight, desire, lust, and longing that is unwholesome, unhealthy, and unsupportive.

-

Chanda: pleasure, delight, desire, love, and aspiration that is wholesome, healthy, and supportive.

Motivation of Craving

Taṇhā may be translated as ’thirst’, ’craving’, ’yearning’, ’infatuation’, ’fervour’, ’lust’, ’agitation’, ’anxiety’, or ’insatiability’.35

According to the teaching of Dependent Origination, taṇhā is conditioned by feeling (vedanā) and rooted in ignorance (avijjā). When one receives a pleasurable or displeasurable sense impression – one sees a delightful or loathsome visual form, for example, or hears a melodious or grating sound – and feels either pleasure, pain, or a neutral feeling, craving arises in one form or another. If one experiences pleasure, then one is glad, delighted, satisfied, fascinated, enthralled, and covetous. If one feels pain, then one is displeased, dissatisfied, and averse, and one wishes to escape or wishes for the feeling to disappear. If one feels a neutral feeling then one remains indifferent and complacent.

These reactions occur automatically; they require no thinking or understanding. (On the contrary, if a person reflects on or understands the process, for example if one knows that the loathsome visual object is beneficial or the melodious sound is in fact an alarm signalling danger, or one is aware that the object is unsuitable on the grounds of ethical or cultural considerations, then craving can be severed and the habitual process can be replaced by a new form of behaviour.) Craving is dependent on feeling and is reinforced by ignorance: it ’rests upon’ feeling and is grounded in ignorance.

Because craving is directly tied up with feeling, a person with craving searches for things that will provide pleasing, delightful feelings. There are six distinct things that can provide feeling: visual forms, sounds, smells, tastes, tactile objects, and mental objects.

The first five – sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and tactile objects – are connected to the material world and are particularly pronounced. They are referred to as the five objects of sensual enjoyment (kāma-guṇa).36 The six sense objects, and especially the five objects of sensual enjoyment, are both the aim and the source of craving. Craving is thus a thirst for things that provide sensation and a thirst for pleasing sense objects – a desire for pleasing sense objects in order to experience delightful feelings. (See Note Craving Arising and Ceasing) In brief, craving is the desire to acquire. {986}

To say that craving arises from the six sense objects or from the five cords of sensual pleasure is a concise explanation. A detailed explanation by the Buddha is that craving arises from things that are pleasurable (piya-rūpa) and agreeable (sāta-rūpa), of which there are ten groups of six items: the six internal sense organs, the six external sense objects, the six forms of consciousness, the six kinds of contact, the six kinds of feeling, the six kinds of perception, the six kinds of volition, the six kinds of craving, the six kinds of applied thought (vitakka), and the six kinds of sustained thought (vicāra). Craving is both established at these pleasurable and agreeable things and abandoned and ceases at these things.

D. II. 308-311; S. II. 108-109; Ps. I. 39-40; Vbh. 101-103.

Craving has further repercussions: the experience of contacting sense objects and experiencing feelings gives rise to a mistaken belief that there is a stable, lasting self that experiences these feelings.

Accompanying this belief in a stable, lasting self is a craving for this self to endure. But this biased belief is merely an idea (that is, it is not based in reality), and it tends to generate an opposing belief that inclines in the opposite direction, that the self exists only temporarily, that it is impermanent and will eventually disappear.

These beliefs are connected to the feelings resulting from contact with sense objects: the existence of a self is defined and determined by the experience of pleasant feelings. When a person is gratified by sense contact, the craving for the stability of the self is intensified. But when the person is not gratified by sense contact then the stability of the self loses significance. If the dissatisfaction with sense contact is strong then there arises an aversion for the stability of the ’self’: a person wishes for the self to be separated from the present state of existence or craves for the destruction of the self. This alternative form of craving – for annihilation of the self – goes hand in hand with the belief that the self exists temporarily and will eventually disappear.

These two forms of craving – for stability of the self and for self-annihilation – exist as a pair and lie in juxtaposition to one another.

The first kind of craving – a desire for pleasant sense objects – is also a desire for sense objects to satisfy the ’self’ or a desire for the self to experience pleasant feeling from sense objects.

All forms of craving merge at or serve a sense of self.

People allow these different forms of craving to direct the course of life, by pandering to them, nourishing them, and faithfully obeying them. They are the source of all problems, both personal and social, and they generate expectation, fear, doubt, anger, hostility, carelessness, obsession, and conflict. There are three distinct kinds of craving:

-

Kāma-taṇhā: craving for pleasant sense objects to satisfy a sense of self; craving for sensuality.

-

Bhava-taṇhā: craving for the importance, stability, and immortality of the self; craving for existence.

-

Vibhava-taṇhā: craving for the destruction, escape, or annihilation of the self; craving for non-existence. {987}

In brief, these three kinds of craving may be referred to as craving for sense pleasure, craving for existence, and craving for non-existence.37

According to the Buddhist teaching on the mode of conditionality (paccayākāra), craving leads to ’seeking’ (pariyesanā or esanā, see Note Craving and Seeking): the search to obtain desired objects, which results in acquisition. The acquisition of a desired object marks the end of one stage in the conditional process.

Before examining this process more closely, take note that seeking is not the same as doing, and seeking may not involve any form of physical action, as will be discussed below.

Taṇhaṁ paṭicca pariyesanā: ’with craving as condition, there is seeking’; pariyesanaṁ paṭicca lābho: ’with seeking as condition, there is acquisition.’

(D. II. 58-9; A. IV. 400-401; Vbh. 390-1; cf.: S. II. 143 where craving is expressed as the term chanda).

Pariyesanā can also be translated as ’endeavouring to obtain’ or ’acknowledging’.

At DA. II. 499, AA. IV. 188 and VinṬ.: Parivāraṭīkā, Ekuttarikanayo, Navakavāravaṇṇanā taṇhā is classified as two kinds:

esanā-taṇhā (craving in the search for desired objects) and

esita-taṇhā (craving for things sought after and acquired).

Nd. I. 262 and DA. III. 720 mention five kinds of chanda:

desire in searching (pariyesana-chanda),

desire in acquisition (paṭilābha-chanda),

desire in consuming or using (paribhoga-chanda),

desire in accumulation (sannidhi-chanda), and

desire in distributing (visajjana-chanda: to hand out money or feed people to increase one’s following);

These two passages explain that these five kinds of chanda are all expressions of taṇhā.

Motivation of Wholesome Desire

At this point let us return to the term chanda, which we have defined as desire for wholesome qualities (kusaladhamma-chanda), love of virtue (kusala-chanda), or love of truth (dhamma-chanda).

Kusaladhamma-chanda is translated as desire for wholesome qualities: an enthusiasm for and delight in virtue.38 Kusala-chanda is translated as love of virtue; although the term dhamma is removed, kusala-chanda has an identical meaning to kusaladhamma-chanda.

Kusala may be translated as ’wholesome’, ’skilful’, ’favourable’, ’proficient’, ’healthy’, or ’salubrious’: it refers to things that are beneficial to a person’s life, things that promote wellness and prosperity for an individual and for society. (See Note Definitions of Kusala) {988}

Dhamma-chanda is translated as love of truth or a desire for truth. The term dhamma often has a general meaning, referring to ’thing’ or ’teaching’, but in this context its meaning is more far-reaching.

Here, dhamma has two principal meanings: first, the ’truth’ (or teachings that reveal the truth), and second, ’virtue’ (’goodness’, ’virtuous quality’, and to some extent ’ethics’). Dhamma-chanda can thus be rendered as ’love of truth’, ’love of virtue’, ’desire for truth’, or ’desire for virtue’.

The desire for truth points also towards knowledge: a person wants to know the truth, to realize the truth, to realize the true meaning, true essence, and true value of things.

And the desire for virtue is linked to action: a person wishes to generate goodness.

There are three principal definitions for kusala:

ārogya (an absence of illness; healthy);

anavajja (faultless); and

kosalla-sambhūta (arising from skilfulness; arising from wisdom).

Alternative definitions include:

’resulting in happiness’ (sukha-vipāka) and

’peaceful’ (khema).

See, e.g.: PsA. I. 129, 206; DhsA. 38, 62; DA. II. 645; VismṬ.: Khandhaniddesavaṇṇanā, Viññāṇakkhandhakathāvaṇṇanā.

Dhamma-chanda can therefore be translated as ’intent on truth’, ’love of truth’, ’intent on goodness’, or ’love of goodness’. It includes an aspiration for knowledge, a desire to act, an eagerness to act. A simple definition for dhamma-chanda is ’intent on truth’, with the understanding that all the aforementioned explanations are included in this definition. In a similar fashion, the term chanda on its own can also be translated as ’intent on truth’.

Chanda desires truth and virtue; it desires a knowledge of truth; it desires to act in order to give rise to goodness and to produce truly beneficial results. Chanda is thus related to action, specifically action performed in order to know the truth and to create goodness.

Why is it that when wholesome desire (kusaladhamma-chanda) is mentioned in the texts, it is usually linked to the desire to act (kattukamyatā)? The desire for knowledge and goodness solicits action. In order to arrive at knowledge, truth, and fulfilment, one must act. To use a play on words, to access the real one must have zeal.39

For this reason, the desire to act is an attribute of wholesome desire or the love of truth. One can even say that the term chanda is a synonym for kattukamyatā: the desire to act is wholesome desire. Sooner or later, when the texts mention wholesome desire (kusala-chanda) or the love of truth (dhamma-chanda), they normally conclude by stating that chanda is equivalent to the desire to act (kattukamyatā-chanda).

In reference to the mode of conditionality (paccayākāra), the Buddha said that chanda leads to perseverance (ussāha),40 or he mentioned chanda as preceding effort (vāyāma) or energy (viriya).41 Put simply, chanda generates action (just as taṇhā generates seeking).

Related to this subject, the commentaries say that the cause of wholesome desire (chanda) is wise reflection (yoniso-manasikāra).42

This passage indicates that wholesome desire is part of a conditional process involving wisdom. Wholesome desire commences when a person begins to apply wisdom (just as the arising of craving depends on ignorance). {989}

Comparative Analysis

To sum up:

-

Craving (taṇhā) is focused on feeling (vedanā) and desires objects in order to experience feeling, or desires objects for personal gratification. Craving is generated and sustained by ignorance; it is linked to personal issues – it centres around a sense of ’self’. It leads to seeking.

-

Wholesome desire (chanda) is focused on wellbeing, on what is truly beneficial and on the quality of life; it desires truth, goodness, and virtue; it desires fulfilment and wholeness. Chanda is generated from wise reflection; it is objective – it is not bound up with a sense of ’self’; and it leads to energy, effort, and action.

There are two points here requiring special emphasis:

-

When analyzing whether a person’s actions (including thoughts and speech) are dictated by craving or not, one can use the following criteria: desires or actions that are tied up with a search for gratifying sensations, that protect or promote the stability of a fixed sense of ’self’ (including on a deeper level the undermining of the ’self’), are matters that fall under the category of craving.

-

The passages ’craving leads to seeking’ and ’chanda leads to action’ are very helpful in distinguishing between these two qualities. This distinction has a crucial bearing on ethics and on Dhamma practice, which will be discussed below.

Craving desires things in order to experience feeling, and the gratification of craving is achieved through the acquisition of these things. Any method used by craving to acquire gratifying objects is referred to by the term ’seeking’ (pariyesanā). The methods for acquiring these things vary: some methods require action while other methods (for example someone else provides the object) do not require action. In the case that action is required, however, the object desired by craving does not have a direct causal relationship to the action. For example:

’Mr. Gully is a janitor and gets a monthly salary of $300.’

’If you finish reading this book Daddy will take you out to the movies.’

Many people will think that janitorial work is the cause for receiving the salary: cleaning is the cause and the salary is the result. Such a conclusion, however, is false; it stems from an habitual and self-deceptive way of reasoning.

For the statement to be accurate one must insert missing clauses: the action of cleaning results in a clean building; a clean building is the true result of cleaning. Receiving a salary for cleaning is merely the result of an agreement made by certain individuals. There is no certain causal relationship between these two events: some people who clean buildings receive no money and most people receive a salary without having to clean buildings.

The second example is similar: many people will think that reading the book is the cause and going to the movies is the result, but in fact the true result of reading a book is the gaining of knowledge. To finish reading the book is merely a condition for going to the movies. {990}

In the first example, if Mr. Gully’s behaviour is compelled by craving, then he cleans only because cleaning is a requirement for getting money. He does not desire a clean building and he does not want to sweep and clean.

In the second example, the child wishes to go to the movies and she reads the book only because it is a condition for getting the object desired by craving: to see a movie. She does not desire the knowledge contained in that book and she has no wish to read the book.

Strictly speaking, craving does not lead to action nor does it generate a desire to act. In these cases, action is merely one possible method (following a pre-arranged agreement) used for attaining sought-after objects according to the needs of craving.

These two examples also clarify the quality of chanda, which desires virtue, truth, and knowledge of the truth.

With chanda, Mr. Gully would desire a clean building and the child would desire the knowledge from the book; both individuals desire the direct results of these actions. The results ’appeal to’ the causes: the results help determine the course of action. Action is equivalent to generating desired results; cause and effect are intimately linked. When Mr. Gully sweeps, cleanness arises, and it arises every time he sweeps. When the child reads, knowledge arises, and it continues to arise the more she reads.

Chanda desires the virtue resulting from action, and thus also desires the action itself, which is the cause for that virtue.

In this sense, chanda leads to action and leads to a desire to act. This helps to explain why the second kind of chanda (kattukamyatā-chanda – the desire to act) is equated to kusala-chanda or dhamma-chanda (the desire for virtue or truth).43

If behaviour is guided by chanda, Mr. Gully will have an enthusiasm for sweeping the building that is distinct from receiving a salary, and the child will read the book without her father’s enticement to see a movie. There are many other ethical implications to these two forms of desire, but at this point simply remember the distinction that craving is the desire to consume or experience, while chanda is the desire for truth and action.

Problems Arising from a Set of Preconditions

The ethical or practical consequences of using either craving or chanda as a motivation for action vary greatly.

When a person uses craving as the motivation, action is merely a prerequisite for obtaining desirable objects in order to satisfy the sense of ’self’. The person does not directly desire the action or the results of the action; his or her direct aim is to obtain the desired objects.

In many instances the required action is merely one method of obtaining the desired objects.

Therefore, if one is able to find a method of obtaining these things without having to act, one will use this method and avoid doing anything, because obtaining the desired objects without having to work is most compatible with craving.

And if it is impossible to avoid action then one will act reluctantly, unwillingly, and without real enthusiasm. {991}

The consequences of craving are as follows:

-

When one tries to avoid having to perform the prearranged action, one may seek a shortcut or an easy alternative to acquire the desired object without having to work. This avoidance may even lead people to behave immorally. For example, if Mr. Gully wants money, has no enthusiasm for or dedication to his work, and feels he cannot wait, he may seek money by stealing. If the girl cannot put up with reading the book, she may steal money from her mother and go to see the movie alone rather than wait for her father to take her.

-

When one craves to acquire and has no desire to act, one will perform required actions simply to get them over with, act in a hasty fashion, or act to convince others that one has accomplished the deed. The result is a lack of precision and excellence in one’s work. And one will develop bad habits like disinterest in achievement, negligence, and half-heartedness. For example, Mr. Gully may joylessly sweep day in and day out, waiting for his salary. The girl may read the book in a distracted way without gaining any knowledge or deceive her father by reading only the first, middle, and final page and claim she has finished it.

-

When the original agreements have been breached, there arises underachievement, carelessness, avoidance, and deception. As a consequence, strict secondary preconditions need to be established for support and protection. But this is only attending to symptoms, making the entire system more complicated and confusing. For example, it may be necessary to find a supervisor and inspector for Mr. Gully’s work and verify the hours he has spent working. It may be necessary to have an elder sibling check on the girl or else the father may need to cross-examine her on the book’s content.

When craving dictates behaviour in response to these secondary terms and conditions, new layers of faulty and immoral conduct arise until the entire system becomes disrupted or useless.

-

When the desired object differs from the direct result of an action, then the value of the action cannot be measured by its result because the action is being performed to serve some other goal. In such a case, there is an imbalance between the action and desired results. The behaviour of people who aim for desired objects expected under the terms of an agreement is likely to be either excessive or deficient, and is likely to be inadequate for realizing the beneficial, virtuous results stemming directly from that action. People then determine the value of the action by the acquisition of desirable objects.

The basic rule for action performed as a prerequisite for acquiring desired sense objects, or the distinctive rule of craving, is: ’The more I obtain desirable things, the more I act’, or: ’The more I experience delightful feelings, the more I act.’ Action based on this premise is never-ending and possesses a flip side of: ’If I don’t acquire desirable objects, I won’t act’, or: ’If I don’t experience delightful feelings, I’ll remain idle.’

Apart from being defective and a missed opportunity, action that is performed for results differing from its direct, beneficial results also creates negative effects. A simple example is that of eating: when a person eats purely with craving, then if the food is delicious he will eat till he is bloated; if the food does not appeal to his desires then he will eat too little, leading to discomfort and sickness. (The action is eating, which results in adequate nourishment for the body and is a prerequisite for experiencing delicious tastes.) {992}

The negative effects of craving are widespread as will be discussed in further examples below.

-

In the case that action and the things desired by craving are not directly aligned by cause and effect, craving is averse to action and resists work. Craving attempts to avoid work by trying to obtain things through no effort at all, and when it is essential to act, then people act begrudgingly. People acting with craving (following prescribed terms and conditions) tend to find no joy or satisfaction, either in the action itself or in the fruits of their labour.

The things desired by craving abide virtually in isolation, disconnected from the deed. As long as one does not acquire the desired objects, the craving for these things remains. And acting to fulfil certain preconditions may further incite craving, leading to disturbance and anxiety.

The state of mind of someone who acts with craving is restless, confused, stressful, and nervous, and is often accompanied by other unwholesome qualities like fear, distrust, and envy.

A lack of fulfilment and dissatisfaction can lead to severe personal problems, like stress and mental illness. When these problems extend outwards, they create difficulty for one’s life in general and cause affliction for others.

Benefits of Wholesome Desire

People who apply wholesome desire (chanda) as the motivation for action, on the other hand, wish for the direct results of actions, and therefore they also want to act. The consequences of wholesome desire are opposite to the consequences of craving:

-

Wholesome desire leads to upright behaviour, diligence, and honesty, to sincerity in relation to one’s work, and to a steadfast allegiance to the natural law of causality.

-

Wholesome desire creates an enthusiasm for work; it leads to precision and excellence in relation to one’s work, to a wish for success, to earnest endeavour, and to being undaunted by work.

-

Instead of a complicated system of control and mutual fault-finding, there is cooperation and a coordinated effort between people, because each individual wishes for the success of the work rather than yearning for personally gratifying objects which are scarce and must be competed for.

-

Because the action is performed for its own direct results, the value of the action can be measured by its results. There is a balance between the action and desired results: a person acts in order to give rise to beneficial results. For example, one eats the proper amount to meet the needs of the body and to promote health, without being enslaved by delicious flavours. {993}

-

When one desires the direct results of an action and wants to generate these results, one also realizes the intermediate benefits that arise during the course of action. The wish to act and the reaping of benefits from action leads to satisfaction, contentment, happiness, and a deep sense of peace.44

In the context of Dhamma practice, chanda is classified as one of the ’paths to power’ (iddhi-pāda), which is a vital principle for the development of concentration (samādhi). Wholesome desire brings about concentration, which the Buddha called ’concentration as a result of desire’ (chanda-samādhi).45 Wholesome desire promotes mental health, as opposed to craving, which creates mental illness.

Even in the case when a person is unable to fully accomplish the results of an action, wholesome desire does not create suffering or mental problems. Whether the action bears fruit or not, it proceeds according to cause and effect: the effects are consistent with the causes; the causes along with any obstructing conditions naturally give rise to specific results. Wholesome desire does not create suffering because those people who act with such desire have an understanding of causality and recognize the direct results of their actions.

Suffering only arises when craving is given the opportunity to interfere, for example when one worries that people will be critical for not succeeding or one compares one’s accomplishments with the success of others. (See Note Thinking as Conceit)

The Act of Eating Subject to Preconditions

Following are some everyday examples of these principles:

When the body is underfed then it requires food for nourishment and for sustaining life. The need for food manifests as hunger, which we can distinguish as the first stage in the act of eating. Hunger is a function of the physical body and is classified as a result (vipāka). From the perspective of ethics, it is neutral: neither good nor bad, neither wholesome nor unwholesome. Even arahants experience hunger.

This form of thinking falls under the category of ’conceit’ (māna), but craving here must also be firmly established: there must be a desire for the stability of the ’self’, which is connected to the conceit and wish to be recognized as a ’success’.

See the passage at Paṭ. 205, which states that the fetter of conceit (māna-saṁyojana) is dependent on the fetter of greed for existence (bhavarāga-saṁyojana); it arises due to causes and conditions. (It is most likely that important parts of this passage have been lost, as confirmed by the complete passage referred to at VismṬ.: Khandhaniddesavaṇṇanā, Saṅkhārakkhandhakathāvaṇṇanā.)

The Abhidhamma states that the proximate cause (padaṭṭhāna) of māna is greed (lobha), and that māna only arises in a mind that is rooted in greed (lobha-mūla) or accompanied by greed (lobha-sahagata).

Put simply, conceit is a consequence of craving.

See: Dhs. 247; Comp.: Cetasikaparicchedo, Akusalacetasikasampayoganayo; CompṬ.: Cittaparicchedavaṇṇanā, Akusalacetasikasampayoganayavaṇṇanā; Vism. 469.

Hunger is a stimulus. It prompts the act of eating, and it conditions the behaviour of eating: if one is very hungry one eats a lot; if not very hungry, one eats less. {994}

Hunger, however, is not the sole conditioning factor for eating; there are other reasons why people eat.

At the second stage of eating, for ordinary, unawakened beings, another incentive or motivation comes into play and determines behaviour along with hunger: the force of craving.

There are two kinds of craving that manifest at this stage: first, is the struggle to protect the security of the ’self’ (the craving for existence – bhava-taṇhā), which is obvious in times of great hunger or starvation. Craving generates anxiety, agitation, and a fear of death, accompanying the normal discomforts of going without food. The stress and fear will be commensurate to the degree of craving. At this point the person seeks food. When craving directs behaviour, the search for food tends to be desperate and disregards ethical considerations. (See Note Seeking and Craving)

The second kind of craving is the craving for sense pleasures (kāma-taṇhā): the hunger for delightful sensations. The craving for sense pleasures combines with physical hunger to condition behaviour, either as a support or as an obstruction. This is similar to two people who are in competition for material gains; if both gain, they help each other; if only one party gains, they are in conflict.

If hunger is the sole factor, then the degree of hunger determines the amount of food a person eats; if craving is the sole factor, then the degree of delicious flavours determines the amount of food consumed.

This, however, is only a hypothetical argument: usually, craving never allows hunger to be the sole determining factor. Craving almost always intervenes, and when hunger and craving exist as co-determinants, hunger obliges craving, by helping to enhance the experience of delicious flavours. But hunger can only help to a limited extent; it cannot always accommodate the desires of craving. {995} As a consequence, a person may be very hungry but the food is not tasty and he eats too little, or he is not hungry but the food is delicious and he overeats; or he is only a little bit hungry and the food is not tasty, so he refuses to eat anything.

Hunger is a warning, announcing the body’s requirements. When a person eats to satisfy hunger then the body receives adequate nourishment; the direct result of eating is nourishing the body. But when a person eats with craving – eats to experience delicious flavours – then he sometimes eats too little and other times too much, which can harm the body.

In the case of craving, tasting delicious flavours is dependent on the act of eating, but it is not a direct result. Eating is the direct cause for nourishing the body but it is a prerequisite for the gratification of craving.

People may raise the question that if the act of seeking stems from craving, then does this mean that someone without craving needs not seek food?

The Pali word pariyesanā (’seeking’) is used to define all methods applied for acquiring desired objects. It has a broad meaning, including methods that require action and methods that do not require action. ’Seeking’ here is distinguished from pure action. Whenever seeking is directly linked to its results then it is merely an action in the ordinary sense.

For instance, in the above example, the body requires food for sustenance and good health. Seeking is an immediate cause for obtaining required nourishment, and is thus an action performed for its own direct results.

The distinguishing factor is the reason for eating. If a person eats in order to experience delicious flavours, then the process of cause and effect becomes imbalanced. But if a person eats to meet the body’s requirements, the causal process is unified. A person without craving applies reasoned judgement and understanding, reflecting on the need for food to sustain life and to perform good deeds.

In Dhamma practice, if one’s conduct is based on this kind of reasoned reflection, then one considers the search for food through righteous means to be a responsibility and puts forth effort. Even bhikkhus, who should sustain life with only the minimum requirement of food, endeavour to find food following their own custom and tradition.

See: Vin. I. 57-8, 96: these passages reveal another perspective on the distinction between seeking that is a responsibility and pure action, and seeking that is simply a search for sensual experience without needing to act.

Craving does not necessarily want to eat nor is it particularly interested in the needs of the body. Craving only wants delicious flavours; eating is merely a requirement to obtain these flavours and there is no other option but to eat.

The tastier the food, the more one eats; one does not consider the body’s needs and limitations. Similarly, if the food does not taste good, one refuses to eat. Moreover, one may feel that the entire process of chewing and swallowing is troublesome, disagreeable, and exhausting. In this case the body is a recipient of the act of eating, but without the person necessarily intending to nourish the body.

Figuratively speaking, the living body is one party in a discussion, while the person eating with craving is another party. When the body is undernourished, it requires food, but it cannot eat on its own; it relies on the person to provide it with food. When people are inattentive to the body’s needs or only grudgingly take an interest in a proper diet, the body suffers. Occasionally, when the body is famished, it must complain and grumble in order to get people’s attention. When the body sends the slightest sign of distress, people hasten to eat.

The body looks for ways to entice people to eat, by offering the reward of experiencing delicious tastes. Sometimes the body is not hungry and does not send any signal of discomfort, but people come across delicious food and eat more than the body requires.

Eating has implications for both parties: for the body, eating results in rejuvenation, while for the person, eating results in obtaining delicious flavours.

(In fact, most people do not want to eat; they only want to experience delicious tastes. If someone were required to eat two plates of insipid food, he would have to force himself to do so, but if the food were delicious then he may not be able to wait for the third plate to arrive.)

When the body offers an incentive for people to eat, it simply waits; people will eat delicious foods from their own initiative and the body obtains required nourishment accordingly. {996}

This method of enticement by the body, however, can be harmful and backfire. If one lacks the ability to consider and reflect, one may be utterly deceived by the body and only search for desirable flavours; as a consequence the body suffers. Sometimes one does not eat enough because the food is not delicious; sometimes the food is tasty and one not only eats more than is necessary, but overeats to the extent of causing illness.

The act of eating then does not provide the suitable result of attending to the body’s needs. Moreover, those people who are enticed by delicious flavours often create trouble and distress for other people.

Procreation and Sensual Pleasure

A similar subject is procreation. To use a metaphor, the life force which desires to procreate (or the biological need to reproduce) is one party in a debate, while the person who experiences sensations is another party. The living organism desires to maintain the continuation of its genes, but it is unable to achieve this goal on its own; it requires assistance from people themselves.

To effectuate this goal, the life force seduces people with the reward of pleasant sensations, especially through the physical contact in the act of reproduction. Sexual intercourse has implications for both parties: for the life force it means a continuation of the species; for people it means obtaining pleasurable feelings.

At this stage, the life force is untroubled; it simply waits passively. When people act according to their desires, the life force receives its desired effects accordingly.

But when someone acts not out of a wish to propagate the species, which is the direct result of the action, but rather because it is a prerequisite for obtaining pleasant sensations, the action is imbalanced. The craving to experience pleasure through sexual intercourse may lead to many forms of harmful and extreme behaviour, spreading sexually transmitted diseases and generating crime, affecting both the individual and society at large.

The matter of reproduction is more complex than the act of eating; the imbalance here extends further than the relationship between the action and desired results. People seduced into acting often end up betraying the life force, which is a partner in this intentional act: the individual people only want to experience pleasure and have no wish to provide the life force with its desired goal of reproduction. They act unilaterally, in order to experience pleasure and to gratify desire, at the same time obstructing life and preventing it from obtaining any results of this action.

This alone is acceptable, but when craving increases, people behave offensively and take advantage of or ’defraud’ the life force. Their sole interest is in pleasure and they think up ways to intensify this pleasure. They devise methods to stimulate and spread the fires of craving, to increase the passion in experiencing sense contact. And they create the instruments to experience the most extravagant and heightened sense pleasures possible, as can be seen today by the proliferation of entertainment centres and various places of licentiousness. {997}

In this activity of reproduction people pay no attention and offer no opportunity to the biological needs. And they apply a similar attitude of neglect to other activities like eating, giving rise to various widespread addictions.46

People should deal with this matter of reproduction in ways that are beneficial to themselves and their communities, by fostering sincerity and goodwill. They should develop wisdom, which recognizes the true objective of desire within the order of nature, so that they practise moderation and avoid indulgence. In this way, people’s actions will satisfy both the genuine needs of nature and the personal needs of individuals in a balanced way. Otherwise, the so-called civilization will end in ruin and devour itself, bereft of peace and happiness.

Eating in Moderation

Let us return to the subject of eating. As mentioned earlier, there are two factors conditioning a person’s behaviour in relation to eating: hunger and craving. Indeed, there is another conditioning factor that may play a participatory role in the act of eating: chanda – a desire for truth or a love of goodness.

In the case of hunger, wholesome desire (chanda) wishes for a truly beneficial state of being; it desires a healthy or optimal existence. It desires favourable conditions for life: health, ease, an absence of illness, a freedom from difficulties and from burdens (more than occur naturally), and a convenience for performing one’s responsibilities, especially in regard to spiritual development.

The process in which wholesome desire arises is different from the process giving rise to craving. Craving arises wrapped up in ignorance. When encountering an agreeable object, one is pleased; when encountering a disagreeable object, one is displeased. Craving follows automatically from feeling, without a person needing to think or to have any understanding of the process.47

The process involving wholesome desire is one of ending ignorance; it is a process of wisdom: of applying thought, understanding, and awareness. When one eats, reflection and awareness are involved; one does not allow the indiscriminate reaction of craving to arise along with associated sensations (vedanā). The process of ignorance and craving ends or abates and is replaced by a process of cessation. {998}

The first factor to eliminate ignorance and cut off craving is wise reflection (yoniso-manasikāra), which can also be translated as skilful consideration, correct thinking, or analytical reasoning. (See Note Reflection Nourishes Mindfulness)

Reflection Nourishes Mindfulness

Compare with this teaching:

Wise reflection nourishes mindfulness and clear comprehension; mindfulness and clear comprehension nourishes restraint of the senses….

The perfection of wise reflection perfects mindfulness and clear comprehension; the perfection of mindfulness and clear comprehension perfects restraint of the senses.

A. V. 118-19.

Wise reflection here investigates in this way: ’What is the result of eating?’ ’What is the purpose of eating?’ It is aware that the reason for eating is to nourish the body, to promote health and ease, and that a natural, healthy state of existence is conducive to performing one’s duties. One does not eat primarily for delicious flavours, amusement, or beautification, which would be detrimental to one’s health, lead to the exploitation of others, increase defilements, and be unfavourable to the truly desirable results of eating.48