Awakened Beings

Awakened Beings

Introduction

There is a well-known teaching in the Buddhist scriptures describing the stages of enlightenment – the stages of realizing Nibbāna. This comprises the four paths (magga) and four fruits (phala):

-

The path and fruit of stream-entry

(sotāpatti-magga and sotāpatti-phala). -

The path and fruit of once-returning

(sakadāgāmi-magga and sakadāgāmi-phala). -

The path and fruit of non-returning

(anāgāmi-magga and anāgāmi-phala). -

The path and fruit of arahantship

(arahatta-magga and arahatta-phala).

The first ’path’ of stream-entry is also called ’vision’ (dassana), because it refers to the first glimpse of Nibbāna. The following three ’paths’, of once-returning, non-returning, and arahantship, are collectively known as ’cultivation’ (bhāvanā), since they involve a development in the Dhamma initially realized at the moment of stream-entry.1 {403}

Those who have reached complete realization of Nibbāna, as well as those who obtain a first glimpse of the goal and are thus guaranteed to reach it, are classified as true disciples of the Buddha. They are known as the ’community of disciples’ (sāvaka-saṅgha), as seen for example in the verse praising the attributes of the Sangha: ’They are the Blessed One’s disciples who have practised well.’

There are many special terms used to describe these true disciples. The most frequently used term is ariya-puggala (or ariya), translated as ’cultivated’, ’noble’, or ’far from the foe’ (i.e. far from mental defilement). The term ariya-puggala was originally used in a general sense; only later was it used specifically in relation to the stages of enlightenment.2 The original term used in the Pali Canon when distinguishing the stages of enlightenment is dakkhiṇeyya (or dakkhiṇeyya-puggala). In any case, the terms ariya-puggala and dakkhiṇeyya-puggala were adopted from Brahmanism. The Buddha altered their meanings, as he did with many other words, for example: brahmā, brāhmaṇa (’brahmin’), nahātaka (’washed clean’), and vedagū (’sage’).

The Buddha gave the term ariya a new definition, different from that prescribed by the brahmins. The word ariya (Sanskrit: ārya; English: Aryan) originally referred to a race of people who migrated from the northwest regions and invaded the Indian subcontinent several thousand years ago. As a result of this invasion, the native inhabitants retreated either south or into the forests and mountains. The Aryans considered themselves cultivated; they disdained the native people, marking them as savages and enslaving them. Later, when the Aryans had consolidated their rule and established the caste system, the native peoples were accorded the lowest tier as sudda (Śūdra; labourers). The term ariya (’noble’) designated the three upper castes of khattiya (Kṣatriyaḥ; warriors, kings, administrators), brāhmaṇa (brahmins; scholars, priests, teachers), and vessa (Vaishya; merchants). Suddas and all others were labelled anariya (’ignoble’, ’base’).3 A person’s caste was determined at birth; there was no way to choose or alter one’s position.

When the Buddha began teaching, he declared that nobility does not depend on birth, but rather on righteousness (Dhamma), which stems from spiritual practice and training. Whoever acts in line with noble principles (ariya-dhamma) is ’noble’ (ariya) irrespective of birth or caste. Whoever does not is anariya. Truth is not restricted to the dictates of brahmins and the Vedas,4 but is objective and universal. A person who has realized these universal truths is noble, despite having never studied the Vedas. Because knowledge of these truths makes one noble, they are called the ’noble truths’.5 {404} Technically, those who understand the noble truths are stream-enterers and above. Therefore, the scriptures generally use the term ariya as synonymous with dakkhiṇeyya-puggala (’those worthy of offerings’), a term which will be discussed shortly.

The Four Noble Truths (ariya-sacca) are sometimes referred to as the ariya-dhamma.6 The term ariya-dhamma, however, does not have a fixed definition and is used in other contexts.7 It can refer to the ten ’wholesome ways of action’ (kusala-kammapatha)8 and to the five precepts.9 Such definitions are not contradictory, since those householders who truly keep the five precepts their entire lives, without blind adherence (sīlabbata-parāmāsa) and without blemish, are stream-enterers and above. The standard commentarial definition of ariya in reference to ’noble’ people encompasses the Buddha, Pacceka-Buddhas10 and disciples of the Buddha,11 although in some places the definition refers to the Buddha alone.12 When qualifying a spiritual practice or factor, ariya is equivalent to ’transcendent’ (lokuttara),13 although this is not always strictly the case.14

Although the definition of ariya is rather broad, one can summarize that when the term is used in reference to people it is identical to dakkhiṇeyya-puggala, meaning those who have gone beyond the state of ordinary persons and become members of the sāvaka-saṅgha (today, more often called the ariya-saṅgha). (See also Note Commentarial Categories of Ariyas). In the commentaries and sub-commentaries this definition is almost fixed, with very few exceptions. In the scriptures, the term ariya tends to be used in a general sense, not specifying the level of awakening. Dakkhiṇeyya is the more specific technical term and is used less often than ariya.

Commentarial Categories of Ariyas

Some exceptions include passages at: J. II. 42; 280; J. III. 81; J. IV. 293. The commentaries explain these exceptions by classifying ariya into four categories:

ācāra-ariya – noble by behaviour; those grounded in virtue;

dassana-ariya – noble in appearance; those possessing features that instil confidence;

liṅga-ariya – noble by ’gender’, i.e. those living the life of a spiritual renunciant (samaṇa);

paṭivedha-ariya – noble through realization, i.e. the Buddha, Pacceka-Buddhas and enlightened disciples of the Buddha.

J. II. 42, 280; J. III. 354; J. IV. 291.

The Buddha extended the meaning of the term ariya, referring to members of a new community, i.e. Buddhist disciples who are ennobled by practising the Middle Way. These disciples live ethically, non-violently and in harmony. They are dedicated to promoting wellbeing for all. {405} Their actions are not ruled by the enticements and threats of religious officials, who often cater to people’s selfish needs. Moral principles may be perverted due to the decisions of such religious authorities. An example of this is the sacrifice of animals performed by brahmins.

Dakkhiṇeyya translates as ’one worthy of offerings’.15 The original Brahmanic meaning of this word referred to the payment received for performing ceremonies, particularly sacrifices (yañña; Sanskrit: yajña). The Vedas describe the forms of payment, including: gold, silver, household goods, furniture, vehicles, grain, livestock, young women, and land. The more prestigious the ceremony the greater the reward. For example, in the Ashvamedha (’royal horse sacrifice’) the king shared the spoils of war with the priests. The recipients of these gifts were invariably the brahmins, because they were the only ones entitled to perform the rituals.

When the Buddha began teaching he spoke in favour of abolishing animal sacrifice, and he transformed the meanings of the words yañña and dakkhiṇā. He developed the meaning of yañña into cruelty-free almsgiving, while dakkhiṇā in the Buddhist teachings refers to suitable gifts and faithful donations, not a fee or recompense.16 If it is a reward then it is a reward for virtue, but it is more aptly called an offering in honour of virtue. In addition, these gifts are not excessively lavish, but simple and basic requisites essential for life.17

Persons worthy of these offerings have trained themselves and are full of goodness. They embody a virtuous and joyful life. Their very existence in the world is a blessing to others. When they go out into the wider society and impart these virtuous principles, living as an example and instructing others, they offer a priceless service to the world. And these individuals do not demand or wish for recompense. They rely on the offerings of the four requisites merely to sustain life. Offerings made to such people bear great fruit because the offerings permit goodness to manifest and increase in the world. These people are called ’worthy of offerings’ (dakkhiṇeyya) because offerings made to them yield valuable results. They are also referred to as the ’incomparable field of merit’,18 because they are a source of virtue to blossom and spread in the world.19 {406}

People give suitable remuneration to ordinary teachers; is it not appropriate for people to give simple gifts to those who teach virtue and the ways of truth? In today’s society people whose business causes destruction – harming the economy, the environment, or even human goodness – receive all sorts of lavish rewards.20 Is it not right that those who protect the world and protect virtue by being moderate in consumption should receive support? Those who consume only what is necessary have minimal impact on the world’s resources; they take little and give much in return.

The making of offerings differs from ordinary giving; one does not give out of personal affection, obligation, or an expectation to get something in return. One gives with faith in the power of goodness, appreciating that the recipient is a member of the Buddhist monastic community (saṅgha), or that he or she upholds virtue. In any case, the recipient must possess the necessary qualities to be entitled to these offerings. For example, an unenlightened monk or novice who eats the almsfood of lay-supporters is ’indebted’, despite having moral conduct and making effort in Dhamma practice. He should hasten to free himself from this debt by achieving the state of a dakkhiṇeyya-puggala. Ven. Mahā Kassapa, for example, claimed that he was in debt to the laypeople for seven days, between being ordained and realizing arahantship.21 After his ordination he made effort in Dhamma practice as an unawakened person for seven days, before reaching the fruit of arahantship and becoming one worthy of the offerings by the faithful laypeople.

The commentaries categorize monks and novices who receive offerings in four ways:

-

Those who behave immorally. They do not have the inner qualities fitting for a mendicant and merely wear the outward signs of a monk. They are undeserving of offerings; their use of offerings is called theyya-paribhoga: ’to consume as a thief’.

-

Those who have moral conduct but do not reflect with wisdom when using the four requisites. For example, when eating almsfood they neglect to consider: ’I eat not for pleasure or beautification. I use almsfood only for the maintenance and nourishment of this body, to keep it healthy, to sustain the holy life.’ Such use of offerings is called iṇa-paribhoga: ’to consume as a debtor’.22 {407}

-

Sekha, or the first seven of the eight dakkhiṇeyya-puggala (see below). Their use of offerings is called dāyajja-paribhoga: ’to consume as heirs’. They have the right to use these offerings as heirs to the Buddha, who was supreme among the dakkhiṇeyya-puggala.

-

Arahants, who are freed from the enslavement of craving. Their virtue makes them truly worthy of offerings. Their use of offerings is called sāmi-paribhoga: ’to consume as masters’.23

Here we can see that the term dakkhiṇeyya is used in both social and economic contexts. The principle of offerings (and to some extent the principle of generosity) fits into the wider principle of the Buddhist social structure, of having an independent group of individuals (the monastic sangha) within a wider society. These individuals gain their independence by not seeking benefits from society and not being directly involved in other social institutions. They have their own way of life based on spiritual freedom. They support society by transmitting the Dhamma, without seeking recompense for their work. They live on offerings by members of the wider society, who give out of devotion to the Dhamma in order to preserve the teachings and purify themselves of unwholesome qualities like greed. Offering this support has minimal financial impact on the supporters’ lives.

The recipients (the monastic sangha) are like bees who collect pollen from various flowers to make honey and build their hives, without damaging even the fragrance or complexion of the flowers.24 Indeed, they fertilize the flowers. Because they depend on others to live, they have an obligation to act for the welfare and happiness of all. Although their life depends on others it does not depend on anyone in particular; they rely on the public and in a sense belong to the public, but are subject to no single individual.

In a well-organized society no one should be destitute and forced to beg.25 In such a society religious mendicants live on the offerings of others but the receiving of alms has no resemblance to begging. This system of an independent community that is devoted to spiritual values and provides a necessary balance to the wider society is unique among social systems in the world.

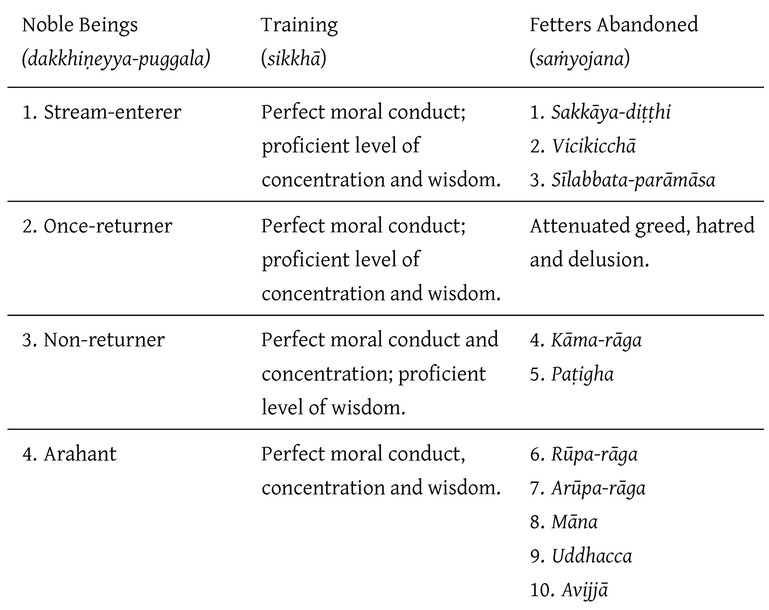

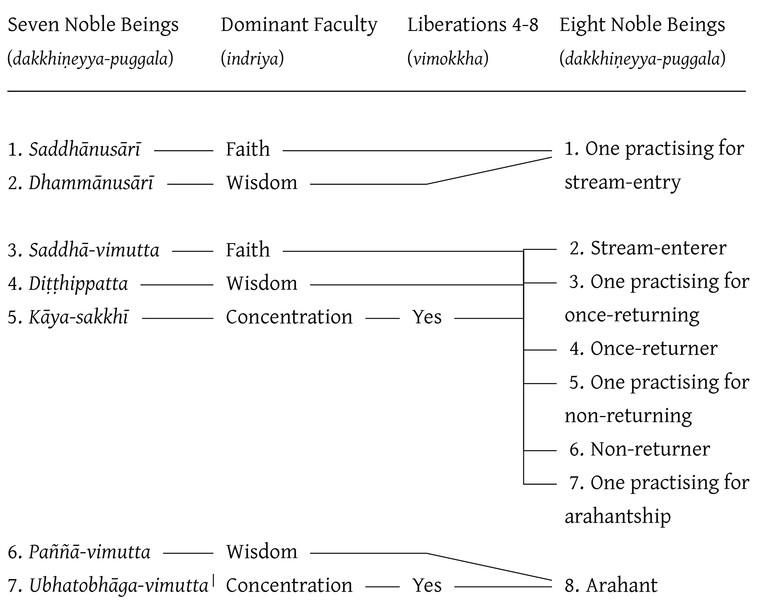

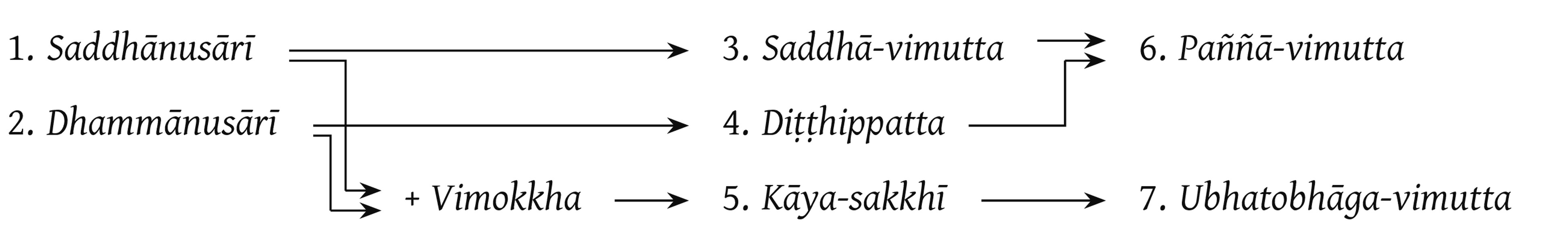

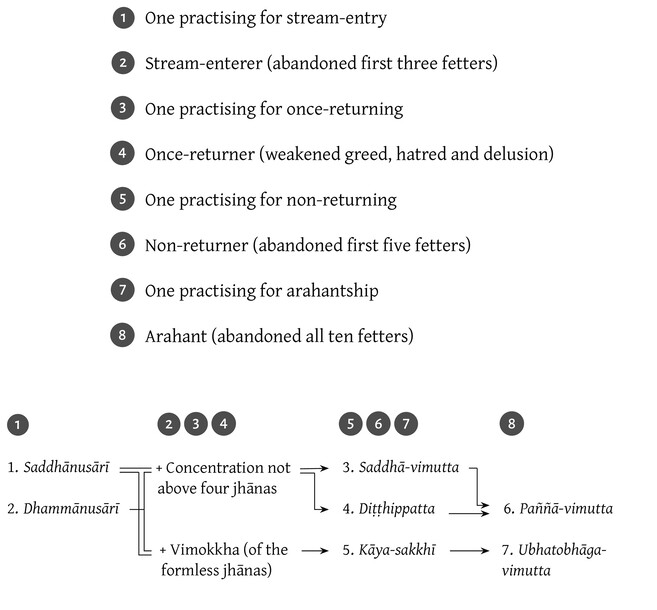

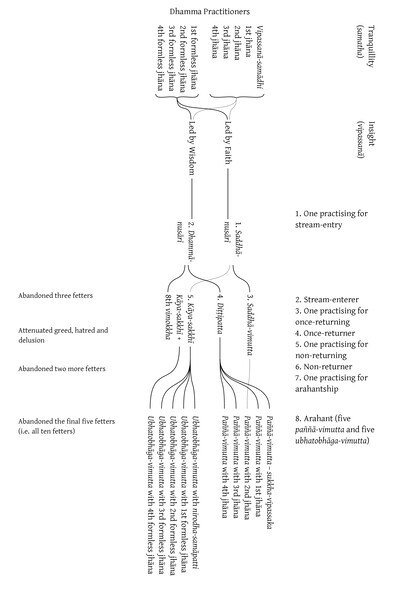

There are generally two ways to categorize dakkhiṇeyya-puggala or ariya-puggala: into the eight levels of eradicating defilements (the eight levels of path and fruit mentioned above), and into the seven qualities or practices that enable the attainment of those eight levels. (The first of these classifications is presented below; the second classification is presented in a following section.)26 {408}

Eight Noble Beings

This division is associated with the ten ’fetters’ (saṁyojana), which are abandoned at different levels of awakening, and with the development of the threefold training (sikkhā) of moral conduct, concentration, and wisdom. The ten fetters are those defilements that bind beings to suffering in the round of rebirth, similar to yokes that bind an animal to a wagon:27

-

A. Five lower fetters (orambhāgiya-saṁyojana):

-

1. Sakkāya-diṭṭhi: self-view; the firm belief in a ’self’; the inability to see that beings are simply a collection of assorted aggregates. This view creates a coarse form of selfishness, as well as conflict and suffering.

The stock definition is: One regards material form as self, or self as possessed of material form, or material form as in self, or self as in material form. One regards feeling as self…. One regards perception as self…. One regards volitional formations as self…. One regards consciousness as self … or self as in consciousness.28

-

2. Vicikicchā: doubt; hesitation; distrust. Doubts, for example, regarding the Buddha, the Dhamma, the Sangha, the training, the direction of one’s life, and Dependent Origination. This doubt generates a lack of confidence, courage, and discernment in walking the Noble Path.

-

3. Sīlabbata-parāmāsa: attachment to moral precepts and religious practices. Attachment to form and ceremony. The mistaken understanding that one will be purified and liberated merely by the act of keeping moral precepts, rules, traditions, and practices. The belief that these rules and practices are sacred in themselves. One follows them with the desire for reward or acquisition. Missing the true purpose of moral precepts and religious observances, one ends up astray or in an extreme form of practice (say of practising extreme asceticism – tapa), not on the Noble Path.29

-

4. Kāma-rāga: sensual lust; desire for pleasurable sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and tactile objects.

-

5. Paṭigha: animosity; irritation; indignation.

-

-

B. Five higher fetters (uddhambhāgiya-saṁyojana):

-

6. Rūpa-rāga: attachment to fine-material form, e.g. attachment to the four jhānas of the fine-material sphere; delighting in the bliss and peace of these jhānas; desiring the fine-material sphere (rūpa-bhava).

-

7. Arūpa-rāga: attachment to immateriality, e.g. attachment to the four immaterial jhānas; desire for the formless sphere (arūpa-bhava).

-

8. Māna: conceit; the view of oneself as superior, equal, or inferior to others.

-

9. Uddhacca: restlessness; mental disturbance; agitation.

-

10. Avijjā: ignorance; not knowing the truth; not knowing the law of cause and effect; not knowing the Four Noble Truths. {409}

-

The eight dakkhiṇeyya-puggala or ariya-puggala can be classified into four types or stages, which are related to the fetters in the following way:30

-

A. Sekha (’learners’) or sa-upādisesa-puggala (’those who still have grasping’):

-

1. Sotāpanna: ’stream-enterers’; those who walk the noble path truly and correctly.31 They have perfect moral conduct and an adequate level of concentration and wisdom. They have abandoned the first three fetters of sakkāya-diṭṭhi, vicikicchā and sīlabbata-parāmāsa.32

-

2. Sakadāgāmī: ’once-returners’; those who will return to this world one more time and eliminate all suffering. They have perfect moral conduct and an adequate level of concentration and wisdom. Apart from abandoning the first three fetters, they have attenuated greed, hatred and delusion to a greater degree than stream-enterers.33

-

3. Anāgāmī: ’non-returners’; they reach final enlightenment from the realm where they appear after death – they do not return to this world. They have perfect moral conduct and concentration, and an adequate level of wisdom. They have abandoned two more fetters, of kāma-rāga and paṭigha, thus abandoning the first five fetters.

-

-

B. Asekha (’those who have finished training’) or anupādisesa-puggala (’those with no grasping’):

- 4. Arahant: ’worthy ones’; those worthy of offerings and respect; those who have broken the spokes of the wheel of saṁsāra; those free from mental taints (āsava). They have perfect moral conduct, concentration and wisdom. They have abandoned the remaining five fetters, thus abandoning all ten fetters.

Sekha, translated as ’learners’ or ’trainees’, must apply themselves to sever the fetters and realize the gradual stages up to arahantship. Asekha, the arahants, are adepts; they have gone beyond training. They have finished their spiritual work and eradicated all defilements. They have reached the greatest good; there is no higher spiritual realization for which to strive.

Sa-upādisesa-puggala are equivalent to the first three dakkhiṇeyya-puggala above. They still have upādi (’fuel’), that is, they still have upādāna (’grasping’) – they still have mental impurities. Anupādisesa-puggala, the arahants, are free from grasping and impurity. Note that upādi here is translated as synonymous with upādāna (’grasping’).34 This differs from the upādi in sa-upādisesa-nibbāna and anupādisesa-nibbāna, which translates as ’that which is grasped’, i.e. the five aggregates. {410} The equating of upādi with upādāna corresponds with the Buddha’s teachings on essential spiritual factors, for example the Four Foundations of Mindfulness (sati-paṭṭhāna), the Four Ways of Success (iddhi-pāda), and the Five Faculties (indriya), which often end with the encouragement that one can expect one of two results from cultivating these factors: either arahantship in this very life, or if there is a residue of clinging, the state of non-returning.35 The term upādi in these contexts refers to upādāna or generally to mental defilement (kilesa).

The eight noble beings are precisely these four ariya-puggala described above, but each level of awakening is subdivided as a pair:36

-

Stream-enterer (one who has realized the fruit of stream-entry).

-

One practising to realize stream-entry.

-

Once-returner (one who has realized the fruit of once-returning).

-

One practising to realize once-returning.

-

Non-returner (one who has realized the fruit of non-returning).

-

One practising to realize non-returning.

-

Arahant (one who has realized the fruit of arahantship).

-

One practising to realize arahantship. (See Note Translations of Pairs)

These days one finds the translation of these pairs as ’fruition of stream-entry’ (sotāpatti-phala), ’path of stream-entry’ (sotāpatti-magga), ’fruition of once-returning’ (sakadāgāmi-phala), ’path of once-returning’ (sakadāgāmi-magga), etc. This translation follows commentarial terminology: for maggaṭṭha and phalaṭṭha see Nd1A. II. 254; Nd2A. 15; KhA. 183; DhA. I. 334; VinṬ.: Pārājikakaṇḍaṁ, Bhikkhupadabhājanīyavaṇṇanā; DA. II. 515 = AA. IV. 3 = PañcA. 191; MA. II. 120; UdA. 306. The terms sotāpatti-magga, sakadāgāmi-magga and anāgāmi-magga do not appear in the older texts of the Tipiṭaka; they first appear in the Niddesa, Paṭisambhidāmagga and the Abhidhamma. In the older texts, the term arahatta-magga is only found in the passages: arahā vā assasi arahattamaggaṁ vā samāpanno and arahanto vā arahattamaggaṁ vā samāpannā: Vin. I. 32, 39; D. I. 144; S. I. 78; A. II. 42; A. III. 391; Ud. 7, 65. In later texts, e.g. the Niddesa, Paṭisambhidāmagga and the Abhidhamma, it is extensively used.

These four pairs of noble beings are known as the sāvaka-saṅgha, the disciples of the Buddha who are considered exemplary human beings and comprise one of the three ’jewels’ (ratana) in Buddhism. The chant in praise of the Sangha includes: ’The four pairs, the eight kinds of noble beings; these are the Blessed One’s disciples’ (yadidaṁ cattāri purisayugāni aṭṭha purisapuggalā esa bhagavato sāvaka-saṅgho).37

In the scriptures, these disciples of the Buddha are later referred to as the ’noble sangha’ (ariya-saṅgha). In the older texts, the term ariya-saṅgha is used only once as a synonym for sāvaka-saṅgha, in a verse of the Aṅguttara-Nikāya.38 In the commentaries it is used frequently, especially in the Visuddhimagga.39 When the term ariya-saṅgha gained popularity over sāvaka-saṅgha, the term sammati-saṅgha was used to refer to the bhikkhu-saṅgha. Sammati-saṅgha means the agreed-upon or authorized sangha, referring to any gathering of more than three bhikkhus. These terms are often paired: sāvaka-saṅgha with bhikkhu-saṅgha, and ariya-saṅgha with sammati-saṅgha. In any case the terms ariya-saṅgha and sammati-saṅgha do not contradict the older terms and offer a valuable perspective on the meaning of the word ’sangha’. {411}

Attributes of an Arahant

{343} The teaching of Buddhism is practical and emphasizes things that lead to insight and wellbeing.40 Buddhism does not encourage conceptualizing and debating over things that should be realised through practical application, unless it is necessary for basic understanding. In relation to the study of Nibbāna, rather than discussing the state of Nibbāna directly, it may be of more value to study those persons who have realized Nibbāna, as well as the benefits of realization apparent in the life and character of such persons.41

We can gain some insight into the nature of arahants by looking at the epithets used for them in the scriptures. Here is a selection of these epithets, which express appreciation for their virtue, purity, excellence, and degree of spiritual attainment:

-

Anuppatta-sadattha: one who has attained wellbeing.

-

Arahant: ’worthy one’; a person far from mental defilement.

-

Asekha: one who has finished training; a person not requiring training; a person possessing the qualities of an adept (asekha-dhamma).

-

Kata-karaṇīya: a person who has done what had to be done.

-

Khīṇāsava: a person free from mental taints (āsava).

-

Mahāpurisa: a person great in virtue; one who acts for the welfare of the manyfolk; one who has self-mastery.

-

Ohitabhāra: one who has laid down the burden.

-

Parama-kusala: a person possessing superior wholesome qualities.

-

Parikkhīṇa-bhava-saṁyojana: one who has destroyed the fetters (saṁyojana), which bind people to existence.

-

Sammadaññā-vimutta: a person released through consummate knowledge.

-

Sampanna-kusala: a person perfected in wholesomeness.

-

Uttama-purisa: a supreme person; a most excellent person.

-

Vusitavant or vusita brahmacariya: a person who has fulfilled the holy life. {344}

Many other terms were originally used by other religious traditions, but their meaning was altered to accord with the essential principles of Dhammavinaya, for example:

-

Ariya (or ariya-puggala): a noble person; an excellent person; a person who has developed non-violence towards all beings. Originally, this term referred to members of the first three castes or to those who are ’noble’ (Aryan) by birth.

-

Brāhmaṇa: a ’true brahmin’; a person who has passed beyond evil by abandoning all unwholesome qualities. Originally, this term referred to members of the highest caste.

-

Dakkhiṇeyya: one worthy of offerings. Originally, this term referred to those brahmins who were worthy of a reward for conducting sacrifices.

-

Kevalī or kebalī: a ’whole’ person; a ’complete’ person. Originally, this term referred to the highest individual in the Jain religion.

-

Nahātaka: one who has been ’ceremoniously bathed’; one who has ’bathed in the Dhamma’; one who has purified his or her volitional actions (kamma); one who is a refuge for all beings. Originally, this term referred to a brahmin who passed through a ritual of bathing and was elevated in status.

-

Samaṇa: a tranquil person; one who has quelled the defilements. Originally, this term referred to renunciants in general.

-

Vedagū: a person who has arrived at knowledge; one who is well-versed in knowledge and who is released from attachment to feeling (vedanā). Originally, this term referred to a brahmin who had finished studying the three Vedas.42

To understand the nature of an arahant it is necessary to consider the epithets in the context of the teachings in which they are mentioned, for example: the Three Taints (āsava), the Three Trainings (sikkhā), the Ten Qualities of an Adept (asekha-dhamma), the Ten Fetters (saṁyojana), and the holy life (brahmacariya) as the Eightfold Path.

Many Buddhists tend to describe the attributes of an arahant and of other awakened beings from a perspective of negation, by determining those defilements that have been abandoned or dispelled. For example, a stream-enterer has eliminated the first three fetters (saṁyojana); a once-returner has eliminated these three fetters and further attenuated greed, hatred, and delusion; a non-returner has eliminated the first five fetters; and an arahant has eliminated all ten fetters. Alternatively, they define an arahant briefly as ’one who is without greed, hatred and delusion’ or ’one who is free from defilement’. Such definitions are useful in that they are clear and provide simple standards of evaluation. But they are limited; they do not clearly demonstrate the exceptional characteristics and prominent features of awakened beings, nor do they describe how such beings live virtuous lives and benefit the world at large.

In fact, there are many terms and passages describing the characteristics of an arahant in affirmative ways. Many descriptions or explanations of arahants, however, cover a wide range of subject material, making it difficult to summarize the positive attributes in a clearly defined, well-ordered way. Otherwise, they recount specific incidents and individuals, but do not describe attributes common to all arahants.

An important term in this context is bhāvitatta, which is literally translated as ’one who has developed himself’ or ’one who is self-developed’.43 This term is used for all arahants: the Buddha, the Silent Buddhas (pacceka-buddhā), and all arahant disciples of the Buddha. For example, in the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta, while the Buddha is travelling to the place of his final passing away, he is referred to as the ’Developed One’. {345}

Surrounded by and amidst the group of monks, the Buddha travelled to the river Kakutthā,44 and bathed in and drank from its clear, bright, clean waters…. He travelled to the Mango Grove and said to the bhikkhu Cundaka: ’Lay out an outer robe folded into four layers for me to lie upon.’ And thus prompted by the great Adept (bhāvitatta), Cundaka quickly laid out an outer robe folded into four layers.

D. II. 135.

A similar expression is found in the question by the brahmin student Mettagū:

Blessed One, I wish to make an inquiry. Please tell me the meaning; I will thus consider the venerable sir to be a master of knowledge (vedagū), a fully developed one (bhāvitatta). From where does all this abundant and diverse suffering in the world come?

Sn. 202, in the ’sixteen questions’ – soḷasa-pañhā.

The Buddha compared a ’fully developed one’ – an arahant who is well-versed in the Dhamma (bahussuta) – to a clever ship captain, who is able to guide many people across the seas and reach their destination in safety, as is illustrated in the Nāvā Sutta:

Just as one who boards a sturdy boat, fully equipped with oars and barge-pole, who is experienced and skilful, knowing the methods of helmsmanship, is able to assist many others to cross over the waters, so too, one who is a master of knowledge (vedagū), a fully developed one (bhāvitatta), a highly learned one (bahussuta), stable and unshaken by worldly things, endowed with wisdom, is able to help those who are prepared to listen, in order to investigate the Dhamma and to reach fulfilment.

Sn. 56.

The Loka Sutta is similar to the previous sutta, but covers a broader subject matter, as is evident from the following passage:

Monks, these three kinds of persons appearing in the world, appear for the benefit of many, for the happiness of many, for the compassionate assistance of the world – for the welfare, the benefit, and the happiness of devas and human beings. Which three?

Here, the Tathāgata appears in the world. He is the Noble One, the Fully Enlightened One, perfect in conduct and understanding, the Accomplished One, the Knower of the worlds, the Peerless Trainer of those to be trained, Teacher of gods and humans, the Awakened One, Bestower of the Dhamma. He teaches the Dhamma, beautiful in the beginning, beautiful in the middle, beautiful in the end; he reveals the holy life of complete purity, both in spirit and in letter. Monks, this first kind of person, when appearing in the world, appears for the benefit of many, for the happiness of many, for the compassionate assistance of the world – for the welfare, the benefit, and the happiness of devas and human beings. {346}

Furthermore, there is a disciple of that same Teacher who is an arahant, one whose mind is free from the taints … liberated as a consequence of thorough knowledge. That disciple teaches the Dhamma, beautiful in the beginning, beautiful in the middle, beautiful in the end; he reveals the holy life of complete purity, both in spirit and in letter. Monks, this is the second kind of person, when appearing in the world, who appears for the benefit of many, for the happiness of many, for the compassionate assistance of the world – for the welfare, the benefit, and the happiness of devas and human beings.

Furthermore, there is a disciple of that same Teacher who is still in training, still practising, erudite, engaged in virtuous conduct and practices (sīla-vata). That disciple also teaches the Dhamma, beautiful in the beginning, beautiful in the middle, beautiful in the end; he reveals the holy life of complete purity, both in spirit and in letter. Monks, this is the third kind of person, who when appearing in the world, appears for the benefit of many, for the happiness of many, for the compassionate assistance of the world – for the welfare, the benefit, and the happiness of devas and human beings.

The Teacher, the Supreme Seeker, is first in the world;

Following him, the disciple, adept (bhāvitatta);

And then the disciple in training (sekha-sāvaka), still practising,

erudite, engaged in virtuous conduct and practices.

These three kinds of people are supreme

among devas and human beings.

They radiate light, proclaim the truth,

open the door to the Deathless,

And help to liberate the manyfolk from bondage.

Those who follow the noble Path,

well-taught by the Teacher, the unsurpassed Leader –

If they heed the teachings of the Well-Farer –

Will put an end to suffering in this very life.45It. 78-9. Bahujanahita Sutta

Note, however, that this term bhāvitatta is most often used in poetic verses, rather than in prose. This is most likely because it is concise and can be used easily in verse as a replacement for longer, more drawn-out terms and phrases. Another reason why this short term bhāvitatta tends not to be used in prose is because its meaning is not clearly defined. As there are not the same limitations in prose as there are in poetic composition, longer terms and phrases can be used for the sake of clarity.

At this point it is useful to ask what terms and phrases are used in prose instead of the term bhāvitatta. To answer this question let us look at an explanation found in the Tipiṭaka. The thirtieth volume of the Tipiṭaka – the Cūḷaniddesa – which is considered to be a collection of teachings by the ’commander’ and chief disciple Ven. Sāriputta, elucidates some of the Buddha’s suttas contained in the Suttanipāta. One passage in the Cūḷaniddesa explains the term bhāvitatta as it appears in the question by the brahmin student Mettagū, cited above: {347}

How is the Blessed One an Adept (bhāvitatta)? Here, the Blessed One has developed the body (bhāvita-kāya), developed moral conduct (bhāvita-sīla), developed the mind (bhāvita-citta), developed wisdom (bhāvita-paññā).

(He has developed the four foundations of mindfulness, the four right efforts, the four paths to success, the five faculties, the five powers, the seven factors of enlightenment, the Eightfold Path. He has abandoned the defilements, penetrated the unshakeable truth, realized cessation.)46

Kathaṁ bhagavā bhāvitatto bhagavā bhāvitakāyo bhāvitasīlo bhāvitacitto bhāvitapañño (bhāvitasatipaṭṭhāno bhāvitasammappadhāno bhāvitaiddhipādo bhāvitindriyo bhāvitabalo bhāvitabojjaṅgo bhāvitamaggo pahīnakileso paṭividdhākuppo sacchikatanirodho.)

Nd. II. 14.

Now let us look at a prose passage by the Buddha describing the four areas of self-mastery (bhāvita), which are considered an expansion on the concept of an ’adept’ (bhāvitatta):

Monks, there are these five future dangers as yet unarisen that will arise in the future. You should recognize them and make an effort to prevent them. What five?

In the future there will be monks who are undeveloped in body, morality, mind, and wisdom. Despite being undeveloped in body, morality, mind, and wisdom, they will give full ordination to others but will not be able to guide them in higher virtuous conduct (adhisīla), higher mind (adhicitta), and higher wisdom (adhipaññā).47 These ordainees too will be undeveloped in body, morality, mind, and wisdom. They in turn will give full ordination to others but will not be able to guide them in higher virtuous conduct, higher mind, and higher wisdom. These ordainees too will be undeveloped in body, morality, mind, and wisdom. Thus, monks, through corruption of the Dhamma comes corruption of the discipline, and from corruption of the discipline comes corruption of the Dhamma. This is the first future danger as yet unarisen that will arise in the future. You should recognize it and make an effort to prevent it.

Again, in the future there will be monks who are undeveloped in body, morality, mind, and wisdom. Despite being undeveloped in body, morality, mind, and wisdom, they will give dependence48 to others but will not be able to guide them in higher virtuous conduct, higher mind, and higher wisdom. These pupils too will be undeveloped in body, morality, mind, and wisdom. {348} They in turn will give dependence to others but will not be able to guide them in higher virtuous conduct, higher mind, and higher wisdom. These pupils too will be undeveloped in body, morality, mind, and wisdom. Thus, monks, through corruption of the Dhamma comes corruption of the discipline, and from corruption of the discipline comes corruption of the Dhamma. This is the second future danger as yet unarisen that will arise in the future. You should recognize it and make an effort to prevent it.

A. III. 105-106.

This aforementioned teaching by the Buddha is connected to some essential Dhamma principles:

Bhāvitatta49 is a ’word of praise’ (guṇa-pada), a term describing the virtue or superior quality of the Buddha and the arahants, as those who have developed themselves and completed their spiritual training. When one expands on the meaning of this term into the fourfold mastery of physical development (bhāvita-kāya), moral development (bhāvita-sīla), mental development (bhāvita-citta), and wisdom development (bhāvita-paññā), this pertains to the teaching on the four kinds of cultivation (bhāvanā): cultivation of the body (kāya-bhāvanā), virtuous conduct (sīla-bhāvanā), the mind (citta-bhāvanā), and wisdom (paññā-bhāvanā).

Here, one needs to know some fundamentals of the Pali language. The term bhāvita is used either as an adjective or an adverb, describing the qualities of an individual. The term bhāvanā, on the other hand, is a noun, describing an action, a principle, or a form of practice. There is a compatibility between these terms in that bhāvita refers to someone who has fully engaged in bhāvanā. Therefore, one who is developed in body (bhāvita-kāya) has engaged in physical cultivation (kāya-bhāvanā), one who is developed in virtuous conduct (bhāvita-sīla) has engaged in moral cultivation (sīla-bhāvanā), one who is developed in mind (bhāvita-citta) has engaged in mental cultivation (citta-bhāvanā), and one who is developed in wisdom (bhāvita-paññā) has engaged in wisdom cultivation (paññā-bhāvanā).

This is equivalent to saying that an arahant is one who has completed the fourfold cultivation: he or she is accomplished in physical cultivation, moral cultivation, mental cultivation, and wisdom cultivation.

To clarify this matter, here is a brief description of the four kinds of cultivation (bhāvanā):

-

Physical cultivation (kāya-bhāvanā): physical development; to develop one’s relationship to surrounding material things (including technology) or to the body itself. In particular, to cognize things by way of the five faculties (eye, ear, nose, tongue, and body) skilfully, by relating to them in a way that is beneficial, does not cause harm, increases wholesome qualities, and dispels unwholesome qualities.

-

Moral cultivation (sīla-bhāvanā): development of virtuous conduct; to develop one’s behaviour and one’s social relationships, by keeping to a moral code, by not abusing or injuring others or causing conflict, and by living in harmony with others and supporting one another. {349}

-

Mental cultivation (citta-bhāvanā): to develop the mind; to strengthen and stabilize the mind; to cultivate wholesome qualities, like lovingkindness, compassion, enthusiasm, diligence, and patience; to make the mind concentrated, bright, joyous, and clear.

-

Wisdom cultivation (paññā-bhāvanā): to develop and increase wisdom until there arises a comprehensive understanding of truth, by knowing things as they are and by gaining a clear insight into the world and into phenomena. At this stage one is able to free the mind, purify oneself from mental defilement, and be liberated from suffering. One lives, acts, and solves problems with penetrative awareness.

When one understands the meaning of bhāvanā (’cultivation’), which lies at the heart of the aforementioned ways of practice, one also understands the term bhāvita (’adept’), which is an attribute of those who have completed their spiritual practice and fulfilled the fours kinds of cultivation:

-

Physical mastery (bhāvita-kāya): this refers to those who have developed the body, that is, they have developed a relationship to their physical environment and to their physical bodies; they have a healthy, contented, and respectful relationship to things and to nature; in particular, they experience things by way of the five senses, say by seeing or hearing, mindfully and in a way that fosters wisdom. They consume things with moderation, deriving their true benefit and value. They are not obsessed or led astray by the influence of preferences and aversions. They are not heedless; rather than allowing sense stimuli to cause harm, they use them for benefit; rather than being dominated by unwholesome states of mind, these individuals nurture wholesome states.

-

Moral mastery (bhāvita-sīla): this refers to those who have developed virtuous conduct and developed their behaviour. They act virtuously in regard to society, by keeping to a moral code and living harmoniously with others. They do not use physical actions, speech, or their livelihood to oppress others or to create conflict, but instead they use these activities for self-development, for assisting others, and for building a healthy society.

-

Mental mastery (bhāvita-citta): this refers to those who have developed their minds. As a result, their minds are lucid, bright, spacious, joyous and happy. Their minds are full of virtuous qualities, like goodwill, compassion, confidence, gratitude, generosity, perseverance, fortitude, patient endurance, tranquillity, stability, mindfulness, and concentration.

-

Wisdom mastery (bhāvita-paññā): this refers to those who have trained in and developed wisdom, resulting in an understanding of the truth and a clear discernment of things according to how they really are. They apply wisdom to solve problems, to dispel suffering, and to purify themselves from mental impurities. Their hearts are liberated and free from affliction.

A noteworthy passage in this sutta is where the Buddha states that those monks who have failed to fully develop their body, virtuous conduct, mind, and wisdom, will become preceptors and teachers, but will be unable to guide their pupils in higher virtue, higher mind, and higher wisdom (i.e. in moral conduct – sīla, concentration – samādhi, and wisdom – paññā).

It is interesting that, when describing the qualities of a teacher, the Buddha mentions the four kinds of self-mastery (bhāvita), but when he describes the subject of study – the teaching or the principles of practice – he mentions the threefold training, of moral conduct, concentration, and wisdom. (In full, these are referred to as the ’training in higher virtue’ – adhisīla-sikkhā, the ’training in higher mind’ – adhicitta-sikkhā, and the ’training in higher wisdom’ – adhipaññā-sikkhā.)

This distinction may raise several doubts. First, why doesn’t the Buddha use complementary or corresponding terms here? Wouldn’t it have made more sense for him to say that one who is not fully developed (bhāvita) in the four ways is unable to guide someone else in the fourfold cultivation (bhāvanā), or conversely, one who has not completed the threefold training is unable to guide someone else in moral conduct, concentration, and wisdom? {350}

Moreover, the factors in these teachings are nearly identical. The dual teaching on cultivation (bhāvanā) and self-mastery (bhāvita) contains the four factors of body, virtuous conduct, mind, and wisdom. The Threefold Training, on the other hand, contains the factors of virtuous conduct, concentration (i.e. ’mind’ – citta), and wisdom. Therefore, wouldn’t it have been less confusing if the Buddha had stuck to one or the other of these two teachings, rather than combine them?

Many Buddhists are familiar with the sequence of practice of sīla, samādhi, and paññā, and this threefold practice is considered to be complete in itself. They are generally unfamiliar, however, with this extra factor of ’body’ (kāya), and may wonder why it is added and what it means.

Here, let us simply conclude that the Buddha presented these two distinct teachings in the same context: in reference to the attributes of a teacher he mentioned the fourfold self-mastery (bhāvita), while in reference to the subject of teaching he mentioned the threefold training (sikkhā).

A simple, short answer for why the Buddha used these two distinct teachings in the same context is that they have different objectives or goals. The teaching on the attributes of a teacher aims to describe the discernible characteristics of a teacher, in the manner of evaluating whether someone has completed spiritual training and is ready to teach others. The teaching on the subject of study on the other hand aims to describe the content and system of practice – to describe what and how to train in order to obtain desirable results.

Most importantly, a true study or training entails a natural process of developing one’s life; this process accords with laws of nature and therefore the system of training must be established correctly in harmony with causes and conditions found in nature.

Let us first examine the subject of study, i.e. the threefold training. Why is this training composed of only three factors? Again, one can answer this simply by saying that this training pertains to the life of human beings which has three facets or three spheres of activity. These three factors combine to make up a person’s life, and they proceed and are developed in unison.

These three factors are as follows:

-

Communication and interaction with the world: perceptions, relationships, association, behaviour, and responses vis-à-vis other people and external objects by way of the dvāra – the doorways or channels – which can be described in two ways:

-

Doorways of cognition (phassa-dvāra): the eye, ear, nose, tongue, and body (combined with the meeting point of the mind, these comprise six doorways).50

-

Doorways of volitional action (kamma-dvāra): body and speech (combined with the meeting point of the mind, these comprise three doorways).

This factor can be simply called ’interaction with the world’ and represented by the word sīla (’conduct’).

-

-

The mind: the activity of the mind, which has numerous attendant factors and properties. To begin with, one must have intention, also referred to as volition, deliberation, determination, or motivation. Moreover, people’s minds usually contain positive and negative qualities, strengths and weaknesses. The mind experiences feelings of pleasure and discomfort, ease and dis-ease, and feelings of indifference and complacency. There are reactions to these sensations, like pleasure and aversion, and desires to acquire, obtain, flee, or get rid of, which influence how one experiences things and how one acts, for example whether one looks at something or not, what one chooses to say, and to whom one speaks. This factor is simply called the ’mind’ (citta) or the domain of concentration (samādhi). {351}

-

Wisdom: knowledge and understanding, beginning with suta – knowledge acquired through formal education or by way of the news media – up to and including all forms of development in the domain of thought (cintā-visaya) and the domain of knowledge (ñāṇa-visaya), including: ideas, views, beliefs, attitudes, values, attachments to various ideas and forms of understanding, and specific perspectives and points of view. This factor is called ’wisdom’ (paññā).

These three factors operate in unison; they are interconnected and interdependent. A person’s interaction with the world by way of the sense faculties – by way of the doorways of cognition – and through physical and verbal behaviour (factor #1) is dependent on intention, feelings, and various other conditions in the mind (factor #2). And this entire process is dependent on the guidance by wisdom and intelligence (factor #3). The extent of one’s knowledge determines the range of one’s thoughts and actions.

Similarly, the mental factors of say determination and desire (factor #2) rely on an interaction by way of the sense faculties and physical and verbal behaviour (factor #1) in order to be fulfilled and satisfied. And this process is determined and regulated by one’s beliefs, thoughts, and understanding (factor #3), which are subject to change and adjustment.

Again, the operation and development of wisdom (factor #3) depends on the sense faculties, say of seeing or hearing, depends on the movement of the body, say of walking, organizing, seeking, seizing, etc., and applies speech to communicate and inquire (factor #1). And this process relies on mental properties, for example: interest, desire, fortitude, perseverance, circumspection, mindfulness, tranquillity, and concentration (factor #2).

The nature of human life consists of these three interrelated, interdependent factors. They make up an integrated whole, which cannot be added to or subtracted from. As life consists of these three factors, any training designed to help people to live their lives well must address the development of these three areas of life.

Spiritual training is thus divided into three sections, known as the threefold training. This training is designed to develop these three areas of life to be complete and in harmony with nature. These three factors are developed simultaneously and in unison, resulting in an integrated system of practice.

From a rough perspective one may see these three factors in a similar way as to how they are sometimes outlined in the scriptures, of representing three major stages in practice, of moral conduct, concentration, and wisdom. This perspective gives the appearance that one practices these factors as distinct steps and in an ordered sequence, that is, after training in moral conduct one develops concentration, which is then followed by wisdom development.

By viewing the threefold training in this way one sees a system of practice in which three factors are prominent at different stages, beginning with a coarse factor and leading to more refined factors as one progresses through the stages:

-

The first stage (moral conduct) gives prominence to the relationship to one’s external environment, to the sense faculties, and to physical actions and speech.

-

The second stage (concentration) gives prominence to a person’s inner life, to the mind.

-

The third stage (wisdom) gives prominence to knowledge and understanding.

Note, however, that at each stage the other two remaining factors always function and participate. {352}

This perspective provides an overview, in which one focuses on the chief activity at each stage of the process. One gives prominence to each of the three factors respectively, so that coarser factors are ready to support the growth and promote success of more refined factors.

Take for example the task of cutting down a large tree. First, one must prepare the surrounding area so that one is able to move about easily, safely, and securely (= sīla). Second, one must prepare one’s strength, courage, mindfulness, resolve, non-distractedness, and skill in handling an axe (= samādhi). Third, one must have a proper tool, like a good quality sharpened axe of the correct size (= paññā). If one fulfils these three requirements one succeeds in cutting down the tree.

In regard to one’s regular, daily life, however, a closer analysis reveals that these three factors are constantly functioning in an interrelated, interdependent way. Therefore, in order for people to truly engage in effective spiritual practice, one should encourage them to be aware of these three factors. They should develop these factors in unison, by including skilful reflection (yoniso-manasikāra), which helps to increase understanding, and mindfulness (sati), which helps to bring about true success.

In terms of one’s spiritual practice, no matter what activity one is involved in, one is able to inspect and train oneself according to the principles of the threefold training. One thus aims to engage in all three of these factors – virtuous conduct, concentration, and wisdom – simultaneously and in all situations. When involved in an activity, one considers whether one’s actions result in the affliction or distress of others, whether they cause harm, or whether they are conducive to assistance, support, encouragement, and development of others (= sīla). During such activities, what is the state of one’s mind? Is one acting out of selfishness, malice, greed, hatred, or delusion, or is one acting say with kindness, well-wishing, faith, mindfulness, effort, and a sense of responsibility? While engaged in an activity, is the mind agitated, anxious, confused, and depressed, or is it calm, happy, joyous, content, and bright? (= samādhi). When engaged in an activity, does one act with clear understanding? Does one discern its purpose, objective and related principles? Does one recognize its potential benefits and drawbacks, and fully understand the way to adjust and improve the activity? (= paññā).

In this way skilled persons are able to train and inspect themselves, and evaluate their practice, at all times and in all situations. They cultivate all three factors of the threefold training in a single activity.

Meanwhile, the development of the threefold training from the perspective of three distinct stages unfolds automatically. From one perspective a person develops the threefold training in an ordered sequence. But from another perspective the simultaneous, unified practice of these three factors is taking place and assisting in the successful advancement of the so-called ’three-stage’ training.

In this context, someone who delves deeply into the details of spiritual practice will know that at the moment of awakening – at the moment of realizing Path, Fruit, and Nibbāna – all eight factors of the Noble Path, which are classified into the three groups of sīla, samādhi, and paññā, are completed and operate as one, acting to eliminate the defilements and to bring about fulfilment. {353}

To sum up, the system of Buddhist spiritual training – the threefold training (tisso sikkhā) – is based on a relationship between requisite factors and accords with specific laws of nature. Human life consists of three factors – of conduct with the outside world (sīla), mental activities (citta), and understanding (paññā) – which act in unison and are interdependent in bringing about spiritual development.

When describing the principles of spiritual practice, the Buddha referred to these three aspects of training (sikkhā). We now arrive back at the question: ’Why did the Buddha adopt a new model of the fourfold self-mastery (bhāvita) when he described the attributes of a teacher?’

As mentioned earlier, this question can be answered easily by saying that these two models have different aims and objectives. The threefold training is to be applied in real life – to be practised in accord with a system in harmony with nature. The four factors of self-mastery are intended for self-examination. Here, one need not be concerned with the order of nature. The emphasis here is on getting a clear picture of one’s personal qualities. If one discerns these clearly, they will by their very nature be connected to the three factors of training.

This is obvious by inspecting the first factor of sīla, which refers to one’s interaction and communication with the world, one’s apprehension of the world, and one’s actions in relation to the world.

As mentioned above, we interact with the world by way of two sets of ’doorways’ (dvāra): the first set entails the doorways of cognition (phassa-dvāra), usually referred to as the sense faculties (indriya) – our awareness of the world by way of the eye, ear, nose, tongue, and body. The second set entails the doorways of volitional action (kamma-dvāra), through which we act towards and respond to the world (towards people, towards society, and towards other objects in our external environment) by physical and verbal gestures.

Here lies the distinction. In regard to interacting with the world, at any one moment (or to speak at a more refined level, at any one mind-moment) we only communicate with the world through one of the specific doorways, and one can examine this process by applying either of the two sets of doorways.

In respect to the threefold training, in which sīla, samādhi and paññā are part of an integrated system, the interaction with the world by way of any one of the various doorways comprises the training in ’conduct’ (sīla); the factors of the mind (samādhi) and understanding (paññā) constitute distinct factors. The entire interaction with the world through the various doorways – both the doorways of cognition and the doorways of volitional action – is included here in the factor of sīla. For this reason the threefold training consists of three factors.

In respect to the attributes of a teacher, one need not consider the integrated functioning of the three factors contained in the threefold training. Here, one is distinguishing between different factors for the purpose of investigation. It is precisely here at the factor of conduct (sīla) where a separation is made, that is, one distinguishes a person’s interaction with the world according to one or the other of the two sets of doorways:

-

Doorways of cognition (phassa-dvāra; usually referred to as the sense faculties – indriya): the eye, ear, nose, tongue, and body (along with the meeting point of the mind, these comprise six doorways); these doorways enable seeing/looking, hearing/listening, smelling, tasting, and tangible contact (culminating at the mind as cognition of mental objects – dhammārammaṇa).

-

Doorways of volitional action (kamma-dvāra): body and speech (along with the meeting point of the mind, these comprise three doorways); these enable physical actions and speech (and by designating the starting point of volitional action – the mind – this also includes thinking).

The Buddha separated these two subsidiary factors of conduct (sīla), determining them as the first two factors in the fourfold self-mastery (bhāvita). He distinguished the first factor, of interaction with the world by way of the doorways of cognition or the sense faculties, and labeled it as ’mastery of the body’ (bhāvita-kāya). (The term ’body’ – kāya – here refers to the ’collection of five doorways’ – pañcadvārika-kāya). The Buddha thus gave great emphasis to one’s interaction with the world, in particular to cognition by way of the five senses. {354} People tend to overlook this first factor, but in relation to spiritual practice it is considered of paramount importance in Buddhism, especially in regard to measuring a person’s development.

This is particularly relevant to the present era, which is referred to as the Age of Information or the IT Age. The development of people in regard to this factor determines the fork in the road between direct wisdom cultivation and getting bogged down in delusion. This principle of ’physical development’ can be used as a sign warning people from losing their way, and encouraging them to use information technology to advance civilization in a proper direction.

In terms of measuring people’s spiritual development, the second subsidiary factor, of interacting with the world by way of the doorways of volitional action (kamma-dvāra), constitutes ’moral self-mastery’ (bhāvita-sīla), and is equivalent to the second part of the training in higher virtue (adhisīla-sikkhā). ’Mental mastery’ (bhāvita-citta) and ’wisdom mastery’ (bhāvita-paññā) correspond to the training in higher mind (adhicitta-sikkhā) and the training in higher wisdom (adhipaññā-sikkhā), respectively.

Note that this concept of ’physical mastery’ (bhāvita-kāya), which here has been defined as a development of one’s interaction with the world by way of the five sense faculties, is sometimes explained differently, by defining the term kāya literally as the ’body’ or as referring to material objects.

If one expands the meaning of bhāvita-kāya in this alternative way, then the definition of the second factor of ’moral self-mastery’ (bhāvita-sīla) is adjusted accordingly, as follows: ’moral mastery’ refers to the cultivation of one’s relationship to other human beings or to one’s engagement with society, to promoting peaceful coexistence, cooperation, harmony, and mutual support.

These alternative definitions of these two factors are connected to the teaching on fourfold virtuous conduct – on the four kinds of ’pure conduct classified as virtue’ (pārisuddhi-sīla):

-

Pāṭimokkhasaṁvara-sīla: virtue as restraint in regard to the Pāṭimokkha, the chief disciplinary code of the monastic sangha.

-

Indriyasaṁvara-sīla: virtue as sense restraint; to receive sense impressions, like sights and sounds, mindfully, in a way conducive to wisdom and true benefit, and not to be dominated by unwholesome mind states.

-

Ājīvapārisuddhi-sīla: virtue as purity of livelihood: to earn one’s living righteously and in a pure manner.

-

Paccayapaṭisevana-sīla (or paccayasannissita-sīla): to use the four requisites wisely, benefiting from them by understanding their true purpose and value; to live and consume in moderation; not to consume with craving.

Those aspects pertaining to one’s relationship to the world by way of the body, or to one’s engagement with material objects and with nature, are part of the factor on ’physical mastery’ (bhāvita-kāya). Those aspects pertaining to one’s relationship to society or to one’s community are part of the factor on ’moral mastery’ (bhāvita-sīla).51

Having introduced these principles, the following description of the attributes of arahants corresponds to the teaching on the fourfold self-mastery (bhāvita): being fully developed in body, moral conduct, mind, and wisdom.

Be aware, however, that, although these four kinds of attributes are distinguished from one another, they are not completely separate. Their main features are highlighted for the purpose of understanding, but in the actual process of development they are interconnected and are cultivated in an integrated way. In particular, they are never independent from wisdom. {355}

Physical Self-Mastery (bhāvita-kāya)

Although there are many passages in the Tipiṭaka in which the Buddha mentions the term bhāvita-kāya, there are no explicit explanations of this term, as if the listeners always understood its meaning. There were occasions, however, when non-Buddhists, especially members of the Nigaṇṭhā order, spoke about this subject according to their own understanding, and the Buddha duly responded.

The Mahāsaccaka Sutta, for example, contains an account of such a conversation, in which the terms bhāvita-kāya and bhāvita-citta are discussed:

One morning, the famous Nigaṇṭhā named Saccaka (he was a teacher of the Licchavi princes in Vajjī) travelled to where the Buddha was staying, and engaged him in conversation. He began by speaking about physical cultivation (kāya-bhāvanā) and mental cultivation (citta-bhāvanā). He told the Buddha that according to his opinion the Buddha’s disciples only strive in the area of mental cultivation, but they do not engage in physical cultivation. The commentaries state that the reason Saccaka held this view is that he observed the bhikkhus going off in search of seclusion, but that they did not practise severe austerities.

After he had stated his opinion, the Buddha replied by asking him what, according to his learning, is the meaning of ’physical cultivation’ (kāya-bhāvanā). Saccaka answered by defining it as the practice of severe austerities and self-mortification (atta-kilamathānuyoga).

The Buddha went on to ask him about his understanding of ’mental cultivation’ (citta-bhāvanā), yet Saccaka was unable to provide an explanation. The Buddha continued by saying that Saccaka’s understanding of physical cultivation is incompatible with the cultivation as found in the noble ones’ discipline (ariya-vinaya). Failing to understand the meaning of physical cultivation, how could one possibly understand mental cultivation? He then bid Saccaka to listen to his explanation on what is not physical and mental cultivation, and conversely, what is truly physical and mental cultivation:

How, Aggivessana,52 has one gained mastery in body and mastery in mind? Here, pleasant feeling arises in a well-taught noble disciple. Although touched by that pleasant feeling, he does not lust after pleasure, he does not become one who lusts after pleasant feeling. That pleasant feeling of his ceases. With the cessation of the pleasant feeling, painful feeling arises. Touched by that painful feeling, he does not sorrow, snivel, and lament; he does not weep beating his breast and become distraught.

In this way, Aggivessana, although that pleasant feeling has arisen in him, it does not invade his mind and remain, because the body is developed. And although that painful feeling has arisen in him, it does not invade his mind and remain, because the mind is developed.

Look here, Aggivessana, any noble disciple in whom, in this double manner, arisen pleasant feeling does not invade his mind and remain because the body is developed, and arisen painful feeling does not invade his mind and remain because the mind is developed, has gained mastery in body and in mind.53 {356}

M. I. 237.

As mentioned above, the principal meaning of ’physical cultivation’ (kāya-bhāvanā) is the development of the ’collection of five doorways’ (pañcadvārika-kāya), that is, of the five faculties (indriya): the eye, ear, nose, tongue, and body. Therefore, ’physical cultivation’ (kāya-bhāvanā) is essentially identical to the cultivation of the sense faculties (indriya-bhāvanā).

The development of the sense faculties begins with sense restraint (indriya-saṁvara), to which the Buddha gave great emphasis in the training for those who have ’gone forth’ in the Dhammavinaya. Sense restraint is a fundamental practice, linked with the training in virtuous conduct (sīla). (In the commentaries, sense restraint is often classified as a form of virtuous conduct, as ’virtue as sense restraint’ – indriyasaṁvara-sīla.) Let us have a look at this basic principle:

And how, Sire, is a monk called a guardian of the sense doors? Here a monk, on seeing a visible object with the eye, does not grasp at its major signs or secondary characteristics. Because the evil, unwholesome states of covetousness (abhijjhā) and indignation (domanassa) would overwhelm him if he dwelt leaving this eye-faculty unrestrained, so he practises guarding it, he protects the eye-faculty, develops restraint of the eye-faculty. On hearing a sound with the ear … on smelling an odour with the nose … on tasting a flavour with the tongue … on feeling a tangible with the body … on knowing a mind object with the mind, he does not grasp at its major signs or secondary characteristics … he develops restraint of the mind-faculty. That monk endowed with this noble sense restraint experiences within himself pure, unadulterated happiness. In this way, Sire, a monk is a guardian of the sense doors.

D. I. 70.

Sense restraint still belongs to the practice of a ’trainee’, or is a rudimentary stage of practice. It is not a necessary practice for an arahant, who has ’gained mastery over the sense faculties’ (bhāvitindriya, which is classified as part of bhāvita-kāya). It is included in the discussion here, however, to demonstrate the various stages of practice.

There is a more profound form of sense restraint, or another way of explaining this term, as is evident from a discussion the Buddha had with the wanderer Kuṇḍaliya at Añjanavana in Sāketa. (The cultivation of this form of sense restraint fulfils the three kinds of good conduct – sucarita; the cultivation of the three kinds of good conduct fulfils the Four Foundations of Mindfulness; the cultivation of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness fulfils the seven factors of enlightenment; the cultivation of the seven factors of enlightenment fulfils true knowledge and deliverance, the highest blessing):

And how, Kuṇḍaliya, is restraint of the sense faculties developed and cultivated so that it fulfils the three kinds of good conduct? Here, Kuṇḍaliya, having seen an agreeable form with the eye, a monk does not long for it, or become excited by it, or generate lust for it. His body is steady and his mind is steady, inwardly well-composed and well-liberated. Moreover, having seen a disagreeable form with the eye, he is not dismayed by it, not resistant, not afflicted, not resentful. His body is steady and his mind is steady, inwardly well-composed and well-liberated. Further, having heard an agreeable sound with the ear … having smelt an agreeable odour with the nose … having savoured an agreeable taste with the tongue … having felt an agreeable tangible with the body … having cognized an agreeable mental phenomenon with the mind, a monk does not long for it. … his mind is steady, inwardly well-composed and well-liberated. In this way, Kuṇḍaliya, is restraint of the sense faculties developed and cultivated so that it fulfils the three kinds of good conduct.54

S. V. 74.

Now let us examine a higher stage of practice – the cultivation of the sense faculties (indriya-bhāvanā) – which is described in the Indriyabhāvanā Sutta. After describing this form of practice, this sutta also distinguishes between the term sekha-pāṭipada, referring to an awakened person who is still a trainee, and the term bhāvitindriya, referring to an arahant, who has completed his or her spiritual training and is ’fully developed in body’ (bhāvita-kāya): {357}

On one occasion the Buddha was staying at the bamboo grove in Kajaṅgala, and he was visited by Uttara, a disciple of the brahmin Pārāsariya.55 The Buddha asked him whether Pārāsariya taught the cultivation of the sense faculties (indriya-bhāvanā) to his disciples. When Uttara replied that he did, the Buddha asked him in what manner does he teach on developing the sense faculties. Uttara replied that Pārāsariya teaches to avoid having the eye see material forms and having the ear hear sounds. The Buddha answered that following this line of reasoning a blind or deaf person has ’mastered the sense faculties’ (bhāvitindriya).

The Buddha went on to say that the development of the senses as taught by Pārāsariya is different from the supreme cultivation of the senses in the discipline of the noble ones (ariya-vinaya). Ven. Ānanda then asked the Buddha to explain this supreme cultivation of the senses:

1. The cultivation of the sense faculties (indriya-bhāvanā):

Now, Ānanda, how is there the supreme development of the faculties in the noble ones’ discipline? Here, Ānanda, when a bhikkhu sees a form with the eye, there arises in him what is agreeable, there arises what is disagreeable, there arises what is both agreeable and disagreeable. He clearly understands thus: ’There has arisen in me what is agreeable, there has arisen what is disagreeable, there has arisen what is both agreeable and disagreeable. But that is conditioned, gross, dependently arisen. This is peaceful, this is sublime, that is, equanimity.’ The agreeable that arose, the disagreeable that arose, and the both agreeable and disagreeable that arose cease in him and equanimity is well established. Just as a man with good sight, having opened his eyes might shut them or having shut his eyes might open them, so too in a monk, the agreeable that arose, the disagreeable that arose, and the both agreeable and disagreeable that arose ceases and equanimity is established just as quickly, just as rapidly, just as easily. This is called in the noble ones’ discipline the supreme development of the faculties regarding forms cognizable by the eye.

Again, Ānanda, when a monk hears a sound with the ear … smells an odour with the nose … tastes a flavour with the tongue … touches a tangible with the body … cognizes a mind-object with the mind … equanimity is well established. Just as if a man were to let two or three drops of water fall onto an iron frying pan heated for a whole day, the falling of the drops might be slow but they would quickly vaporize and vanish, so too in a monk, the agreeable that arose, the disagreeable that arose, and the both agreeable and disagreeable that arose ceases and equanimity is established just as quickly, just as rapidly, just as easily. This is called in the noble ones’ discipline the supreme development of the faculties regarding mind objects cognizable by the mind.

That is how there is the supreme development of the faculties in the noble ones’ discipline.

2. A) One who is still in training (sekha-pāṭipada):

And how, Ānanda, is one a disciple in higher training, one who is still engaged in practice? Here, Ānanda, when a bhikkhu sees a form with the eye, there arises in him what is agreeable, there arises what is disagreeable, there arises what is both agreeable and disagreeable; he is discomforted, disquieted and disgusted by the agreeable that arose, by the disagreeable that arose, and by the both agreeable and disagreeable that arose. When a monk hears a sound with the ear … smells an odour with the nose … tastes a flavour with the tongue … touches a tangible with the body … cognizes a mind-object with the mind … he is discomforted, disquieted and disgusted by the agreeable that arose, by the disagreeable that arose, and by the both agreeable and disagreeable that arose. {358} That is how one is a disciple in higher training, one who is still engaged in practice.

2. B) One who has completed the training (bhāvitindriya):

And how, Ānanda, is one a noble one with fully developed faculties? Here, Ānanda, when a monk sees a form with the eye, there arises in him what is agreeable, there arises what is disagreeable, there arises what is both agreeable and disagreeable. If he should wish: ’May I abide perceiving the unrepulsive in the repulsive’, he abides perceiving the unrepulsive in the repulsive. If he should wish: ’May I abide perceiving the repulsive in the unrepulsive’, he abides perceiving the repulsive in the unrepulsive. If he should wish: ’May I abide perceiving the unrepulsive in what is both repulsive and unrepulsive’, he abides perceiving the unrepulsive in that. If he should wish: ’May I abide perceiving the repulsive in what is both unrepulsive and repulsive’, he abides perceiving the repulsive in that. If he should wish: ’May I avoiding both the repulsive and unrepulsive, abide in equanimity, mindful and fully aware’, he abides in equanimity towards that, mindful and fully aware.

Again, Ānanda, when a monk hears a sound with the ear … smells an odour with the nose … tastes a flavour with the tongue … touches a tangible with the body … cognizes a mind-object with the mind, there arises in him what is agreeable, there arises what is disagreeable, there arises what is both agreeable and disagreeable…. If he should wish: ’May I avoiding both the repulsive and unrepulsive, abide in equanimity, mindful and fully aware’, he abides in equanimity towards that, mindful and fully aware.

That is how one is a noble one with fully developed faculties.56

M. III. 298 (abridged)

As mentioned earlier, by expanding on their meanings or by changing the focus of investigation, there are alternative definitions for the terms kāya-bhāvanā and bhāvita-kāya. Instead of focusing on the doorways of cognition or on the sense faculties, the focus shifts to the world at large or to external objects which come into contact with the senses – the objects of cognition. One then distinguishes between these various sense objects. By doing this the definition of ’physical development’ becomes the development of one’s relationship to one’s surroundings by way of one’s physical body, or the development of one’s relationship to material things (including other human beings in their capacity as objects of cognition).

One group of objects that people engage with to a great degree are the four requisites (paccaya): food, clothing, shelter, and medicine. By extension this group also includes all the other material things, consumable objects, tools and appliances used in work, etc., which comprise a large part of our interaction with the outside world. This area of a person’s life requires discipline and training, as one can see from the teaching on moral conduct related to a wise use of the four requisites (paccayapaṭisevana-sīla). A wise use of material requisites, like sense restraint, may thus be included in the factor of physical development (kāya-bhāvanā).

In the Dhammavinaya, the relationship to material things that nourish and sustain life is considered an essential part of training. People are able to develop this relationship constantly in everyday life. This form of training is set down from the onset for those individuals ordained as monks and nuns, of reflecting wisely on the use of the four requisites, and by developing a sense of moderation, which leads to contentment and generates true blessings. This stands in contrast to consuming things with only a foggy understanding and seeking to gratify one’s craving: {359}

Cunda, I do not teach you the Dhamma for restraining the taints that arise in the present alone. Nor do I teach the Dhamma merely for preventing taints from arising in the future. Rather, I teach the Dhamma to both restrain present taints and to prevent future taints from arising.

Therefore, Cunda, let the robe I have allowed you be simply for protection from cold, for protection from heat, for protection from contact with the wind and sun, from horseflies, mosquitoes, and creeping things, and only for the purpose of concealing the private parts and protecting your modesty.

Let the almsfood I have allowed you be just enough for the support and sustenance of the body, for avoiding [malnourishment leading to] distress, and for assisting the holy life, considering: ’Thus I shall terminate old feelings without arousing new feelings and I shall be healthy and blameless and shall live in comfort.’

Let the lodging I have allowed you be simply for protection from cold, for protection from heat, for protection from contact with the wind and sun, from horseflies, mosquitoes, and creeping things, and only for the purpose of allaying the perils of climate and for the enjoyment of seclusion.

Let the medicinal requisites that I have allowed you be just for warding off feelings that have arisen resulting from illness, and for the benefit of being free from afflicting disease.57

D. III. 129-30.